Zymomonas mobilis is good at turning sugar into alcohol. Really good.

People in the tropics have used it since ancient times to brew drinks like pulque and palm wine. Today scientists want to harness the bacterium’s fermentation powers to turn plants into sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels.

But despite years of research we’ve known relatively little about what makes this microbe tick.

Now studies by biofuel researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and its partners have identified the genes that Z. mobilis needs to survive and thrive in various conditions and answered a question that has dogged scientists for decades.

Their findings, published in the journal mBio, could help establish Z. mobilis as a new model organism for understanding related bacteria and will inform future efforts to fine tune it for production of biofuels and other chemicals.

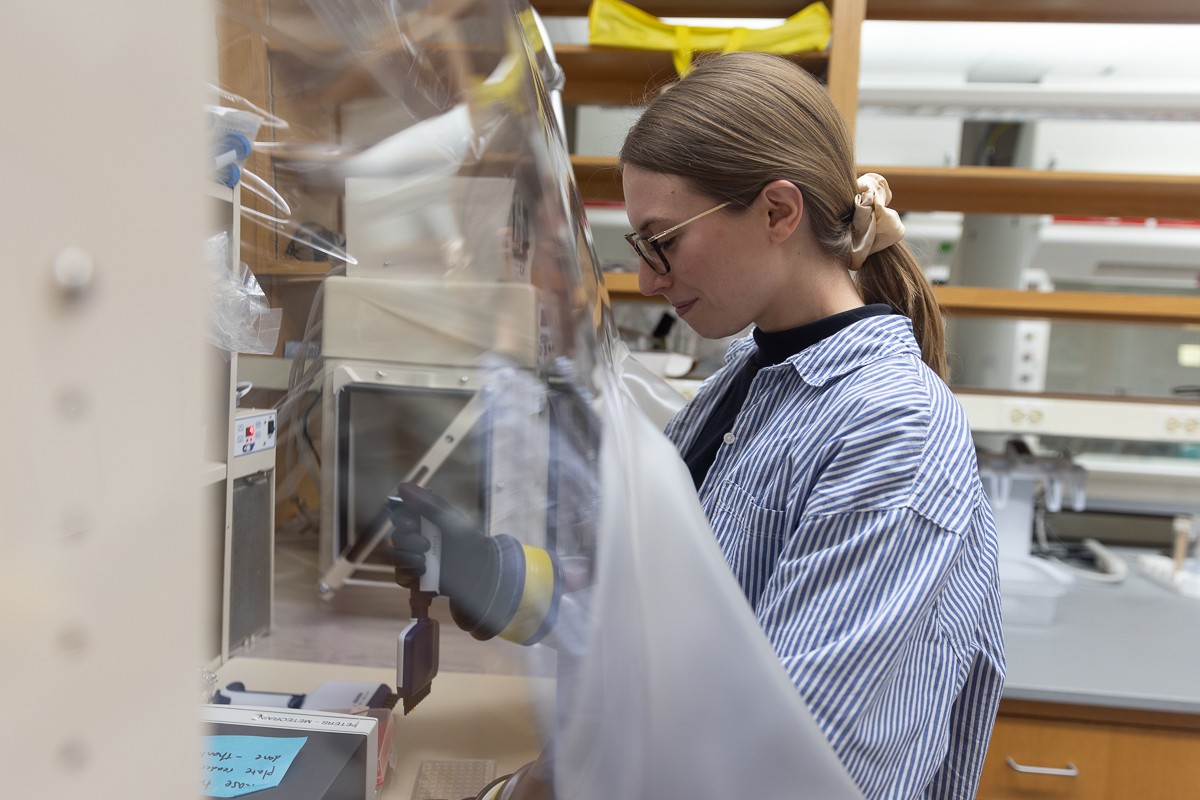

Pharmaceutical sciences professor Jason Peters got interested in Zymomonas shortly after joining the faculty at UW–Madison’s School of Pharmacy in 2018.

As a geneticist, Peters studies bacteria to address some of the greatest threats to human health: antimicrobial resistance, air pollution, and climate change.

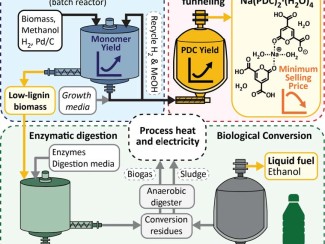

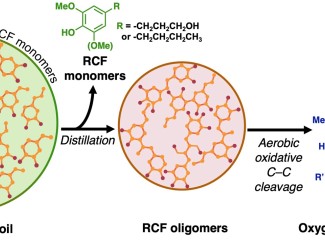

Peters’ work on climate change led him to join the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC), a federally-funded hub based at UW–Madison doing basic science to enable cost-effective and environmentally sustainable fuels and products from non-food plants.

In the mid 2000s, Peters was a graduate student under Bob Landick, a professor of biochemistry and GLBRC science director. Back then, biofuel research was focused largely on yeast and another microbe, Escherichia coli.

But it turns out that Zymomonas had inherent qualities that made it a natural biofuel star.

It’s more efficient than bakers’ yeast at fermenting sugar into ethanol, and unlike E. coli, it can tolerate high concentrations of the product. It has less than half the genes of its closest relatives, making it relatively easy to manipulate, and yet it doesn’t need a host organism. And it can live with or without oxygen.

“It basically had most of the properties that we wanted to evolve E. coli into,” Peters said. “But it already had them, so we didn't need to evolve it.”

A naturally streamlined genome

Z. mobilis is what’s known as a reduced-genome bacterium, genetically streamlined organisms that are easier to study and use industrially than other bacteria whose genetic redundancy can make it harder to understand what each gene does.

“Fewer genes means easier to work with, easier to understand,” said Amy Enright, a doctoral student in Peters’ lab who collaborated on the study. “And so there's a lot of interest in industrial spaces to try to make small genomes and work with small genomes.”

That smaller genome also makes Zymomonas a more efficient biofuel producer. Because it’s not replicating as much of itself (in the form of DNA), Zymomonas can direct more energy and carbon into the fuel.

While scientists can create reduced genome bacteria, experimental genome reduction can result in strains that don’t perform well in certain conditions. Bacteria with naturally reduced genomes have all the benefits of simplicity while also remaining environmentally robust.

“We think what Zymomonas has evolved to do is just do this one thing really, really well,” Enright said.

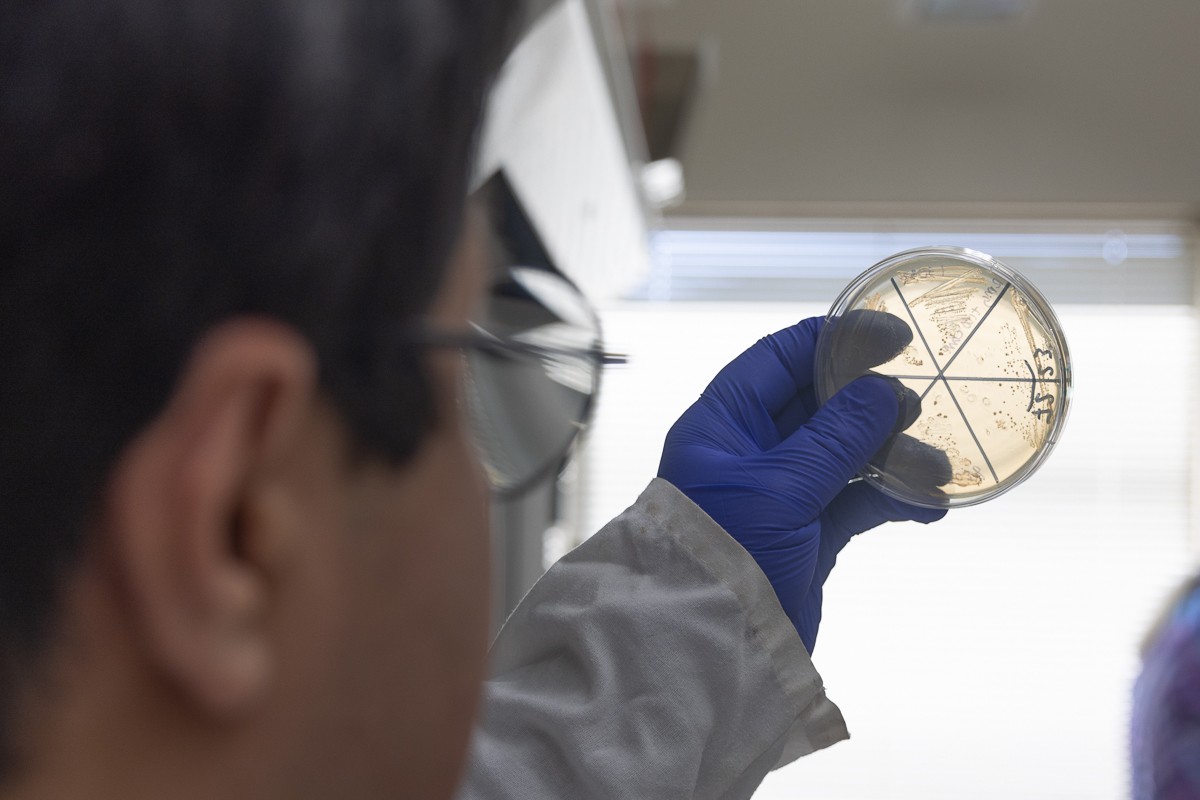

In order to better understand the organism, Peters’ team developed a method for using a tool called CRISPRi to selectively deactivate – or “knock down” the function – of each of the microbe’s 1,915 protein-coding genes in order to see what they do.

The results identified genes essential for survival as well as those Z. mobilis needs to grow with and without oxygen.

“There’s a need to understand both the anaerobic and aerobic lifestyles of this organism,” Peters said. “There's also fundamental biology that we’re interested in. How can it get away with only having 2,000 genes? How different are the gene networks that control aerobic and anaerobic growth?”

Now Enright is focused on identifying which genes are necessary for Zymomonas to grow in plant biomass that’s been chemically broken down into a broth that microbes can digest.

“That broth has some toxins in it that stress the bacteria out, and so they slow down our fermentation and we get less biofuel,” Enright said. “I’m interested in figuring out what genes are important for Zymomonas to grow in the presence of those bioenergy-relevant toxins. Then we could, hopefully, engineer Zymomonas – tweak those genes – so that it grows better in those conditions.”