The Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center has selected staff scientist Avery Vilbert as the recipient of the center’s second annual Yaoping Zhang Bioenergy Research Award for her work in the lab and beyond.

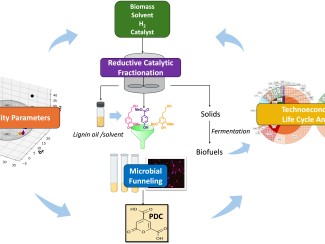

Established in 2024 in memory of the late scientist Yaoping Zhang, the award is given annually to recognize center members who have made important research contributions through high-impact, peer-reviewed publications that advance the center’s scientific mission to develop sustainable lignocellulosic biofuels and products.

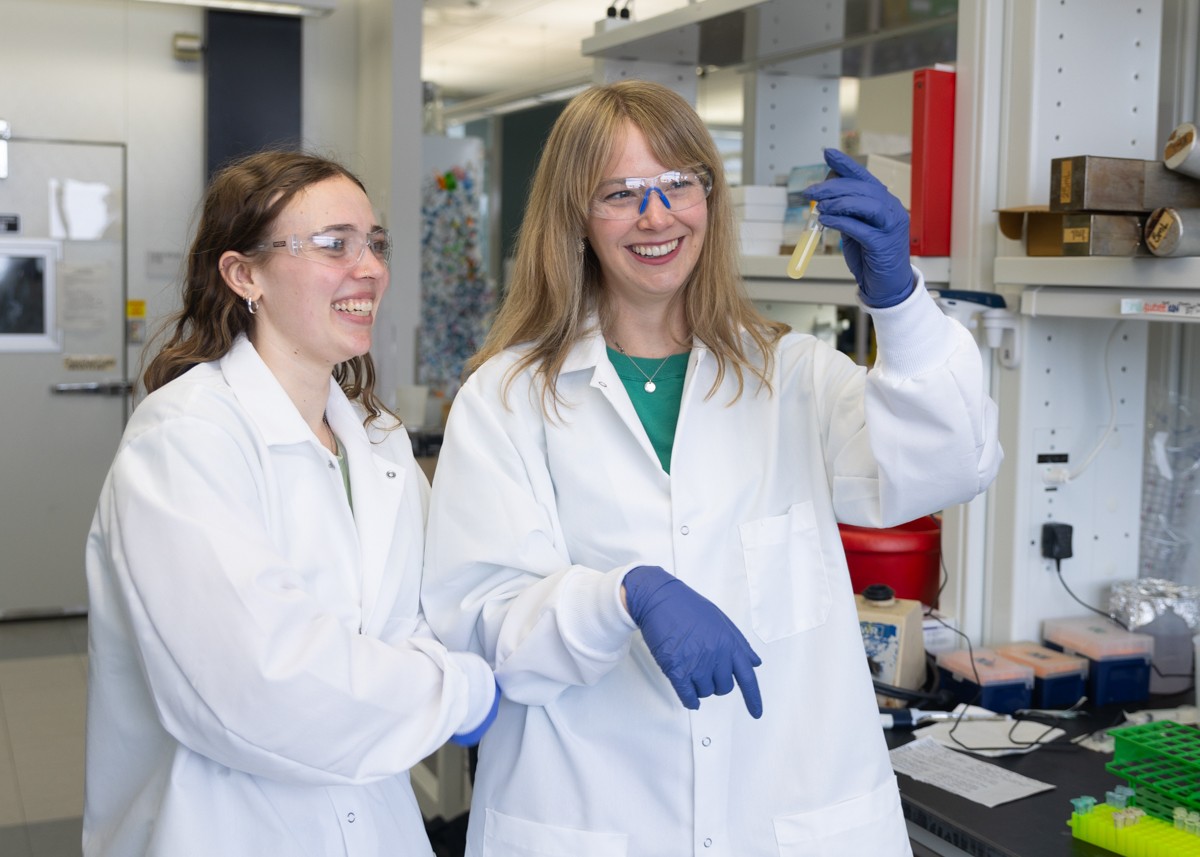

“Avery is an extremely gifted researcher and always happy to lend her experience to help someone,” said research scientist Kevin Myers, who adds that Vilbert has contributed to multiple GLBRC projects, delivered guest lectures, and presented at scientific conferences. “She is always eager to help anyone in her lab or beyond with any project.”

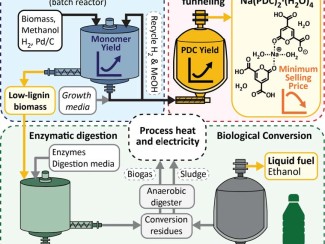

Vilbert joined GLBRC and the Wisconsin Energy Institute in 2020 as a postdoc in the Donohue lab, where she is now a staff scientist studying Novosphingobium aromaticivorans, a bacterium that can eat plant waste and convert it into products used to make bioplastics, cosmetics, and other industrial commodities.

Discovered in hydrocarbon-contaminated soil at a Department of Energy site in South Carolina, N. aromaticivorans evolved to survive in an environment that lacked most of the sugars that most microbes like to eat.

“It developed a bunch of different pathways,” Vilbert said. “Every time I search its genome and start looking for different enzyme functions, Novo seems to already have it, or there’s something unique about it. It’s scrappy, and I find that really interesting.”

Vilbert earned a PhD in chemistry from Cornell University researching enzymes. She’s fascinated by how these proteins work together in cells.

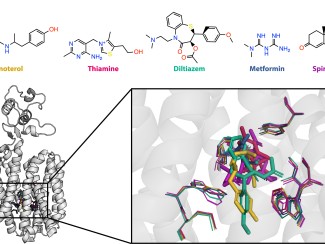

Using genome mining, Vilbert identified several previously unknown enzymes crucial for converting lignin into bioproducts. That work led to a 2024 paper and patent on engineering Novo to produce cis,cis-muconic acid from biomass.

Vilbert’s research goal is to use a systems approach to study enzymes in context of the pathways they build within organisms, which she hopes could eventually lead to microbes that can recycle the same plastics they produce.

“Everything builds on each other,” Vilbert said. “There are patterns that you can pick up. It’s kind of like building blocks by putting enzymes in a row to make a pathway.”

In addition to her research, Vilbert has mentored several undergraduate students who have gone on to become academic researchers and has volunteered for outreach events including Science Expeditions and the Wisconsin KidWind Challenge. Earlier this year she “coached” the microbe to a second-place finish in the Wisconsin Energy Institute’s “Microbial Madness” battle of the bioenergy bugs.

“Being part of GLBRC has been an incredible privilege, offering the opportunity to work in a dynamic, cross-disciplinary environment,” Vilbert said. “Collaborating with colleagues across diverse fields has expanded my skill set in ways I never imagined.”