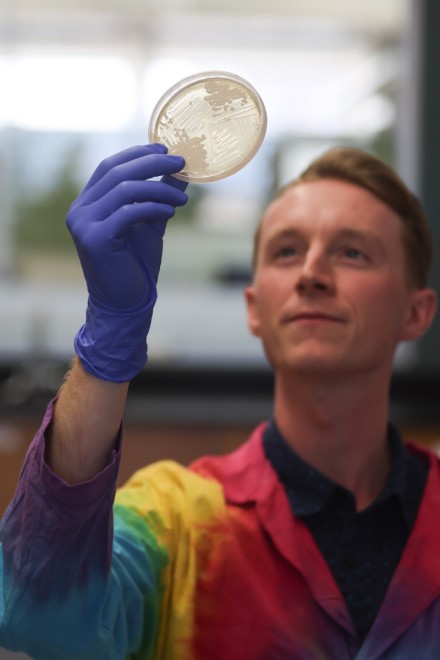

In this series, we learn more about what inspired our talented graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, what brought them to their field of study, and the questions that drive their work as part of the Wisconsin Energy Institute and Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center. Today, we talked to John Crandall, a postdoctoral research associate in the Hittinger Lab. As a yeast geneticist, baker, and brewer, Crandall works with yeast both in and outside of the lab.

What is your focus of research:

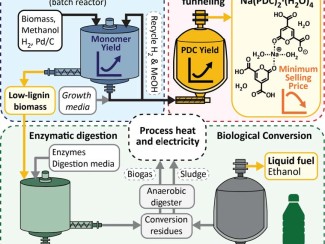

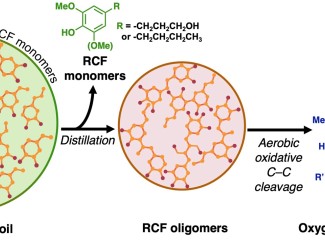

I study the basic biology of yeasts, specifically species that produce a lot of lipids. We then use those insights to biologically engineer these yeasts. By altering their metabolic pathways, we can get them to produce valuable oil compounds and chemicals we would otherwise get from fossil fuels, animals, or plants that require a lot of land and water to produce, such as palm oil.

There's sort of two aims to do it: you can produce compounds in a much less resource intensive manner, or you can replace some fossil fuel based compounds.

What does your typical work day look like?

I spend quite a bit of time at the bench doing molecular biology, which is pretty boring to watch. There's a lot of moving very small amounts of clear liquid between tubes. I also culture strains, and do a lot of work at the computer doing various types of data analysis and comparative genomics and things like that.

What do you like to do outside of work?

I'm trying to spend as much time outside as possible right now. I do a lot of biking, hiking, and skiing. I read a lot, mostly sci fi. I also bake bread and brew beer.

Baking and Brewing? So you work with yeast inside and outside of the lab. What’s your favorite species?

It’s going to be a boring one. But my favorite is probably Saccharomyces cerevisiae, just because that's what we use to make beer and wine.

What attracted you to GLBRC?

I did my PhD here (UW–Madison) and stuck around because I really wanted to dig into the fundamental biology of some of the weird yeast species and wanted to translate that insight into establishing a more sustainable economy and reducing our reliance on fossil fuels. I like doing something that has an impact. I've always loved the thrill of finding out new things that no one else knows. But as time has gone on I’ve become more and more drawn to doing something that blends the thrill of discovery with having a meaningful impact.

How did you get into molecular biology?

I was trained as a basic evolutionary biologist, but I wanted to get into more mechanistic work. After college, I worked in a biochemistry lab that used Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model eukaryote, not necessarily being interested in its its own biology, but just as a model for humans and other systems: extracting DNA, making modifications to it, sequencing and analyzing it.

Do you have any advice for future researchers?

Stay curious. Keep exploring. I think most people are drawn to research because they're curious and interested in the world around them, and it's easy to get sort of pigeonholed and bogged down in your narrow research topic. But I think a lot of the really important connections and novel insights come when you broadly read and talk to people with different backgrounds and experiences. You can do some really important work that way and continue to learn.

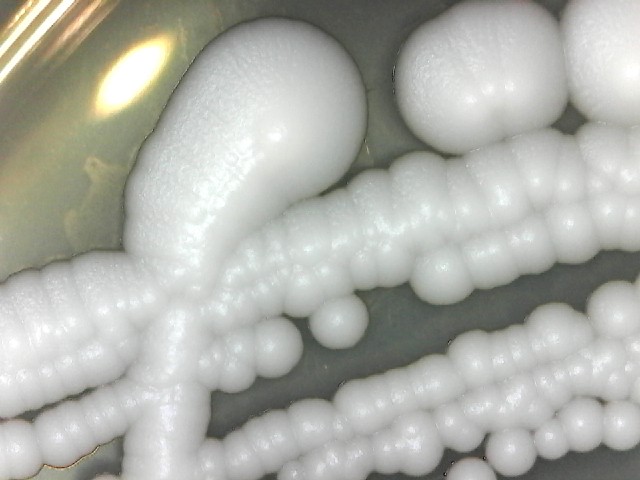

It's a charismatic yeast. It looks nice under microscopes.

John Crandall

What makes a yeast “boring?”

Maybe it's contentious, but certainly there are yeasts that are more or less interesting than others, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae… It's a charismatic yeast. It looks nice under microscopes; a nice… nice shape, not too bumpy or funky looking, but it's not super metabolically complex. It's domesticated, more or less. So most of the strains that we work with have lost a lot of metabolic traits, a lot of the things that make yeasts really good at colonizing new environments and thriving in essentially every biome.

So what would you consider an “interesting yeast?”

A lot of the ones that I work on now I think are really cool. One species that we're doing a lot of work in right now is called Starmerella bombicola. It produces this class of oleochemicals called sophorolipids that are biosurfactants. Basically, sophorolipids can stick to molecules that attract and molecules that repel water, so you can use them to clean up oil spills and produce them industrially to add to household cleaning supplies. What makes that yeast interesting is that it’s acquired a huge portion of its genome from other organisms, and mostly from bacteria. So it's got a lot of really wacky biology going on that we're still teasing apart.