Researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison are working to develop plant-based fuels that are a key piece of the nation’s blueprint for decarbonizing transportation.

The White House released a plan Tuesday for eliminating greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, the nation’s largest source of heat-trapping gasses.

The plan outlines a three-pronged strategy to transform a sector that currently gets more than 95% of its energy from fossil fuels, calling for policies to make transportation more efficient and convenient while also embracing new technologies like electric vehicles and clean fuels.

The cornerstone of the plan is battery-powered vehicles that run on clean electricity, but electrification isn’t practical for applications like airplanes, ships and long-distance freight shipping. And even with widespread adoption of EVs, there will still be millions of older combustion vehicles on the roads after 2040.

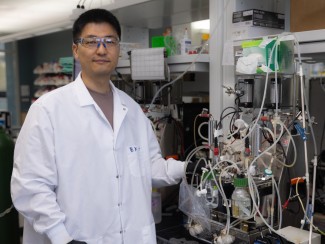

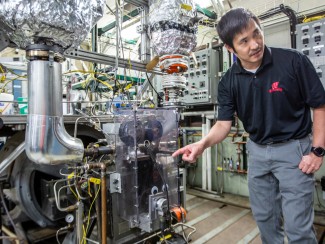

That will require sustainable alternatives to gasoline, diesel and other liquid fuels, said Tim Donohue, director of the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC), a federally-funded research hub based at UW–Madison that is working to develop cost-effective ways to derive fuel and other chemicals from non-food plants.

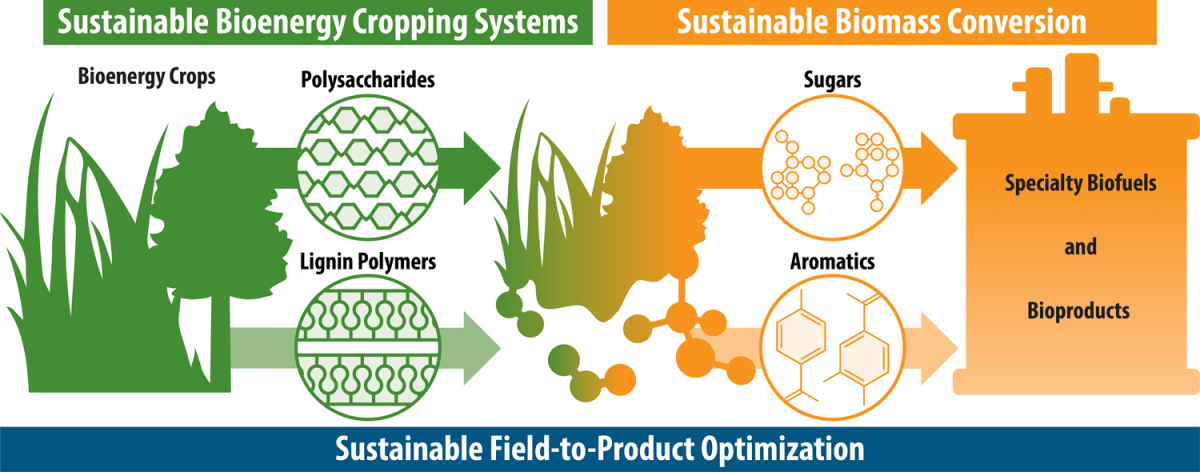

Teams of scientists at GLRBC are coming up with ways to use microbes to produce hydrocarbons from plants like switchgrass, sorghum and poplar that can be grown on land that is unsuitable for food crops. Such fuels use carbon taken from the atmosphere instead of deposits trapped underground for millions of years, making them carbon neutral.

These new biofuels and chemicals, which can be used to make valuable products like polyester, nylon and even acetaminophen, represent a multi-trillion dollar industry.

“Think about how many chemicals we get from fossil fuels,” Donohue said. “The benefits are large even if the new or replacement products are only a small fraction of what society needs."

Donohue said the knowledge could also be applied to turn manure, whey and other agricultural and industrial waste products that currently have little value into abundant renewable resources.

Technology that generates hydrocarbon fuels and chemicals from crops grown on non-agricultural land can reduce carbon emissions without diverting prime farmland and create new economic opportunities for biorefineries, farmers and rural communities that haven’t always benefited from the fuel and chemical industries

That means states and countries that currently import oil could become producers.

While some advanced biofuels are already being produced, Donohue said there is a need for ongoing support, including funding for research and development and policies and incentives to help establish markets.

“It will take years of additional research and investment by the private sector for refineries to produce enough advanced biofuels to cost-effectively meet the anticipated demand,” Donohue said.

Established in 2007 and based at the university’s Wisconsin Energy Institute, GLBRC is one of four national bioenergy research centers funded by the U.S. Department of Energy. With Michigan State University and other collaborators, GLBRC draws on the expertise of more than 400 scientists, engineers, students, and staff to develop sustainable biofuels and bioproducts. GLBRC has trained more than 100 researchers, and produced discoveries contained in some 250 patent applications, that have led to more than 100 licenses and the formation of five start-up companies.