Matt Wisniewski

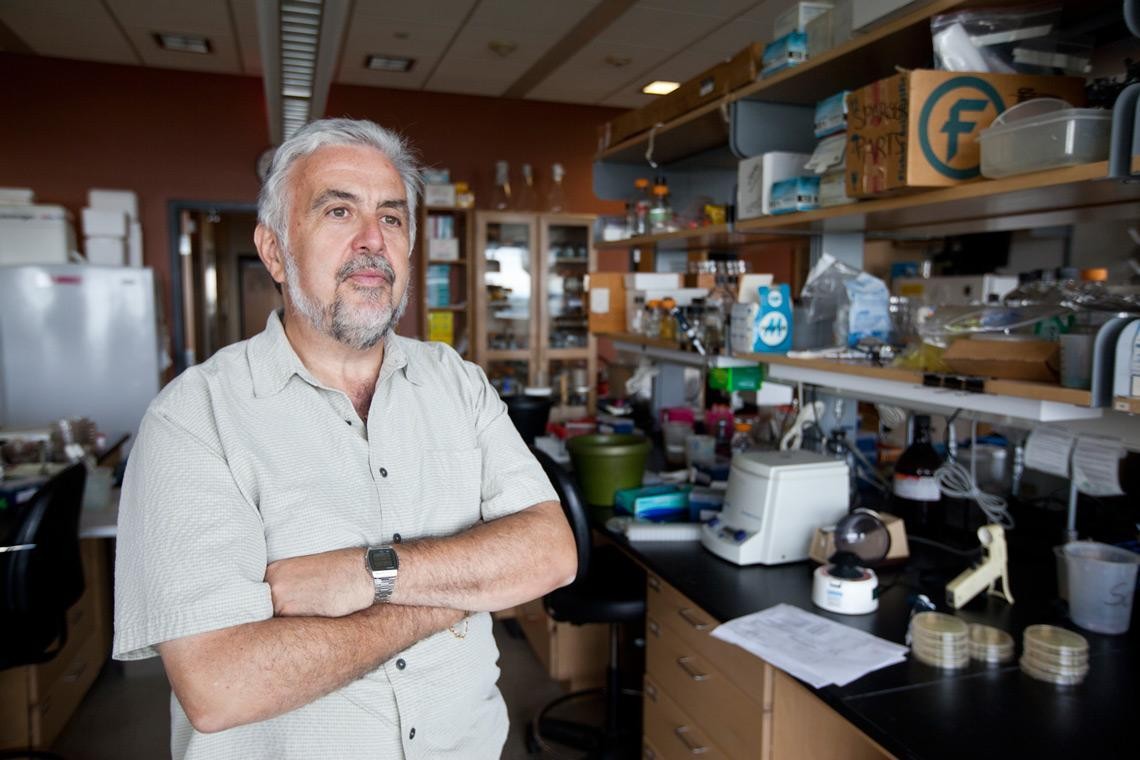

Long before Tim Donohue became the director of the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC), he was a teenage beach cleaner and would-be biologist growing up on the boardwalk of New York City’s Rockaway Beach.

“I was fascinated by the change in the seasons, the tides, the weather, the wildlife,” Donohue says of those early years. “Exposure to the ocean really led me to biology.”

Rockaway, the largest urban beach in the U.S., fed Donohue’s interest in science but it also gave him the cash he needed for college. As a young man, Donohue held two summer jobs, performing routine vehicle maintenance for the National Park Service during the day and emptying Rockaway’s trashcans as the sun set every night.

“I was the first child in our family to go to college,” Donohue says. “My mother had a sixth grade education, my father had an eighth grade education. I think there was probably an implicit expectation that I would go to college, but the idea of me becoming a scientist, getting a Ph.D., that was not really on the table.”

As a college student at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn in the early 1970s, Donohue met Professor Ron Melnick, who introduced him to the world of microbes. The most ancient form of life on earth, microbes are microscopic, single-cell organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Donohue’s love of all things biology had found a tiny new focus.

“I was just fascinated by the power of microbes,” Donohue says, “and by their global impact on our everyday lives. They shaped this planet’s history, they’re central to many of the foods we eat, and they have a huge impact – sometimes positive, sometimes negative – on our bodies and agriculture.”

Melnick also encouraged Donohue to begin working in his lab or, as Donohue puts it, “to drive the car instead of just reading the driver’s manual.” Donohue definitely drove that car, heading to the Pennsylvania State University to pursue a doctorate in microbiology and then on to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for a post-doctoral research fellowship.

Now a professor of bacteriology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Donohue likes to describe his research as “unlocking the secrets” of microbes.

“Microbes have been doing interesting chemistry on this planet for billions of years,” Donohue says. “We can learn a lot from studying how they do what they do.”

I was just fascinated by the power of microbes and by their global impact on our everyday lives. They shaped this planet’s history, they’re central to many of the foods we eat, and they have a huge impact – sometimes positive, sometimes negative – on our bodies and agriculture.

Tim Donohue

Individual bacteria use different strategies to obtain the energy and nutrients they need to live. Some microbes harvest sun light, others have a sweet tooth and prefer to eat sugars. Some digest aromatics, while still others grow by using energy from splitting hydrogen.

“We knew about many of these different processes when I was a student”, Donohue says, “but now, with genomics tools such as DNA sequencing, we can see the actual blueprints of these processes.”

Possessing these exact blueprints gives scientists the information they need to design new pathways that coax bacteria to perform new and desirable tasks.

“In our GLBRC projects, we’re trying to re-task native pathways and engineer next-generation microbial factories that can manufacture valuable fuels and chemicals from renewable wastes.”

While biofuel production is one area of research that will continue to gain from advances in microbiology, the field of microbiology is exceptionally wide-ranging, and enjoying what Donohue calls a “renaissance period.”

Donohue was recently among a group of leading scientists who published a call for a new, government-led “Unified Microbiome Initiative” in the scientific journals Science and Nature. A more coordinated research effort, the authors argue, would go a long way toward harnessing the power of microbes to benefit agriculture and energy production and help address issues such as climate change and disease.

“We’re really at an inflection point,” Donohue says. “Innovation in biology and microbiology can help provide food, health, and energy for a growing population while also ensuring that future generations have access to resources they need to thrive on the planet. That prospect really excites me.”

Donohue, who has published in collaboration with other researchers for much of his career, is a firm believer in coordinated, cross-disciplinary research. As director of the GLBRC, he oversees a team representing a wide array of disciplines and specialties collaborating to overcome a major energy challenge: developing a robust and environmentally sustainable pipeline for biofuels.

“It’s been eye-opening for me to see how GLBRC’s team approach has allowed us to make advances much faster than I ever imagined,” Donohue says. “I never thought we would’ve accumulated the body of knowledge, produced the number of papers, and generated the amount of intellectual property that we have.”

In early 2015, GLBRC reported the filing of its 100th patent application. And to date, the Center has published approximately 850 papers, many of which represent collaborations with researchers from over 32 U.S. states and 24 countries.

Tim Donohue, son of New York City’s so-called Irish Riviera, now occupies an office with a view of the west end of UW–Madison’s campus and is candid about drawing inspiration from the Wisconsin Idea, or the notion that the university should improve people’s lives well beyond the classroom.

“GLBRC really is a proud contributor to the Wisconsin Idea,” Donohue says. “We are doing relevant research that will benefit the state, the region, and the country. It’s been an honor to be a part of this work.”

The GLBRC is one of three Department of Energy Bioenergy Research Centers created to make transformational breakthroughs and build the foundation of new cellulosic biofuels technology. For more information on the GLBRC, visit www.glbrc.org or visit us on twitter @glbioenergy.