Alithic combines carbon dioxide, coal ash to make cheaper, stronger building material

Taken individually, coal ash and excess carbon dioxide are harmful pollutants. Combined in just the right way, they form a durable, inexpensive, and environmentally friendly building material.

University of Wisconsin–Madison spinoff Alithic is leveraging this unique formula to turn waste streams from liabilities into profits, producing a key ingredient of concrete, the most abundant manufactured product in the world.

Based on a discovery by engineering professor Bu Wang, Alithic uses chemical reactions to pull carbon dioxide from the air and mix it with industrial wastes like coal ash, generating a mineral product — known as supplementary cementitious material, or SCM — that can be substituted for traditional Portland cement, one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions.

Instead of adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere to make cement, Alithic’s process locks it away in a product that's cheaper and in some cases stronger than traditional cement.

Cleantech Group, a market intelligence firm focused on emerging technologies, recently named Alithic to a watchlist of 50 early-stage innovators creating groundbreaking solutions to address some of the world’s most pressing environmental and sustainability challenges. Alithic was also a finalist in Cemex Ventures’ green construction startup competition.

“Our new demonstration plant in Madison moves the technology out of the lab and shows this is a commercially-relevant industrial process,” said Rob Anex, a professor of biological systems engineering who co-founded the company with Wang and now serves as an advisor.

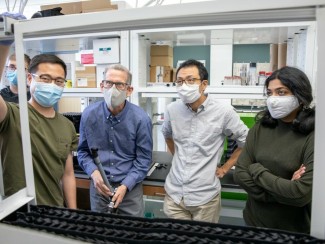

In a nondescript warehouse on the east side of Madison, the core of Alithic’s five-person team is honing the process a few kilograms at a time.

A fan sucks air into a modified cooling tower where it passes over an alkaline solution of sodium hydroxide, which reacts with carbon dioxide. That carbonated solution is then mixed with the coal ash (or similar industrial waste), where the carbon bonds with minerals in the ash to form carbonate and releases sodium hydroxide. The slurry is pumped onto a belt filter, which dries the finished product and drains off the solution to be reused in the first step.

Unlike most direct-air capture technologies, the process requires very little energy.

Fly ash from an ash landfill in Alabama arrives in five-gallon buckets. The treated waste is then shipped to ready-mix concrete plants, where potential customers are testing its binding properties.

Chris Hubbuch/Wisconsin Energy Institute

Many plants already add fly ash to their concrete, said chief technology officer Hamp Thornton, but Alithic’s product contains more reactive silica, which provides greater strength.

“It’s a better product than when we dug it out of the ground,” Anex said.

Alithic is testing other waste streams with calcium or magnesium, including blast furnace slag. But Anex points out that electric utilities have billions of tons of coal ash that must be moved into lined pits to prevent groundwater contamination.

Chris Hubbuch/Wisconsin Energy Institute

“If we can intercept it that’s great,” Anex said. “We’re cleaning up a mess, and we’re making SCM.”

Alithic is now raising the funds to build a ton-scale pilot plant at the National Carbon Capture Center, a research center operated by utility company Southern Company in collaboration with the Department of Energy and other governmental partners in Wilsonville, Alabama.

Anex hopes to begin construction in the next 12 months.

The demonstration plant is a scaled-up and streamlined version of technology Anex and Wang developed in a lab at the Wisconsin Energy Institute with a group of students as part of the Musk Foundation’s XPrize Carbon Removal competition and later refined with the a help of a $2.3 million Department of Energy grant to develop building materials that store carbon.

But since its incorporation in 2023, Alithic has pivoted away from carbon sequestration as a business model.

Though carbon capture tax credits will still generate some revenue — last year Alithic signed a contract to remove 285 tons of carbon for a group of corporate buyers — the spinoff company is focused on the product.

“Our business plan is to sell high quality SCM. Our customers care very little about how much carbon we capture,” Anex said. “That we pull CO2 from the air is a bonus to them, but not something they are willing to pay for — at least today.”