Carbon dioxide removal is needed to mitigate the effects of climate change, but some forms of CDR can be slow, costly, and inefficient.

Since the middle of the last century, rising seas in the South Pacific have swallowed entire islands and washed away swaths of others in the Solomon Islands, forcing residents and in some cases entire communities to relocate. By the end of this century, a projected sea level rise of over three feet will threaten coastal cities like New York and Mumbai.

By 2050 alone, the National Ocean Service predicts sea level rise will routinely disrupt coastal infrastructure. Florida homeowners have already seen astronomical increases to their insurance premiums in no small part due to the damage wrought by natural disasters.

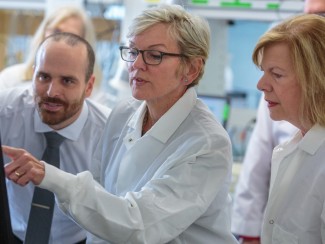

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that we must stop burning fossil fuels by 2050 to slow climate change, but cutting emissions alone will not be enough to avert the increasingly deadly and destructive impacts. We must also use carbon dioxide removal or CDR to eliminate emissions added to the atmosphere since pre-industrial times.

CDR is the process of removing previously emitted carbon dioxide from the air and storing it permanently. If reducing emissions is like fixing a leak, CDR is like mopping up the water that’s already spilled.

Experts agree that CDR is and will continue to be critical to mitigate the effects of climate change, but some forms of CDR can be slow and ineffectual, and commercial CDR technologies are costly to scale and can be hugely inefficienct. Climate hawks fear carbon capture and storage and CDR could provide excuses to continue burning fossil fuels. Yet in spite of the pitfalls, scientists widely agree that CDR investment is necessary.

CDR “is an important opportunity … to kind of hit that reset button,” said Matilyn Bindl, a graduate student in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies who uses computer modeling to study the impact of negative emissions policies.

But CDR independent of a clean energy transition will not slow the effects of climate change, cautions Greg Nemet, a professor of public affairs at UW–Madison and co-author of a 2023 report that calls for a rapid expansion of carbon removal.

“Regardless of what we do on CDR,” Nemet said at a Nov. 28 Wisconsin Energy Institute forum, “we still need to do 80 or 90% emissions reductions by mid century to meet our Paris Agreement temperature target. And so that means immediate and deep reductions, and whether we have CDR … really doesn't change that.”

Bindl said a committment to CDR is a powerful way to steer away from the disastrous effects of unchecked climate change.

“We are trying to answer questions about the future as it pertains to carbon dioxide removal,” Bindl said. “A lot of these technologies are new and still in early stages of development.”

What Bindl refers to as a reset button is needed now more than ever. After a pandemic-induced slowdown, global carbon dioxide emissions have continued rising year-over-year.

Scientists warn that an average global temperature increase above 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century will have devastating effects on the world’s ecosystems.

“For all intents and purposes, that 1.5 is very much in the rearview mirror at this point,” said Rob Anex, a UW–Madison professor of biological systems engineering who specializes in assessing the economic and environmental impact of policies and technologies.

There are two main avenues for pursuing CDR: Conventional methods include afforestation and reforestation, soil carbon sequestration, and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage; and novel methods such as direct air capture, which uses technologies to absorb carbon dioxide directly from the air before storing it.

CDR -- primarily in the form of afforestation -- currently removes about two billion metric tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere every year, according to Nemet's report. That's about a fifth of what's needed in addition to emissions cuts to meet Paris goals.

Natural methods are also challenging. Soil carbon storage is difficult to measure, and permanently storing carbon underground is impossible to guarantee, Anex explained at a Wisconsin Energy Institute Sustainable Energy Seminar. Planting trees requires space, but population growth and the need for arable land may limit what’s available for forest growth.

Forest carbon offset programs have been plagued with fraud, and wildfires and insect infestations can transform forests from carbon sinks to carbon emitters. Canada’s forests are a powerful example. Though the country’s vast forests have provided cover for massive emissions, these trees have released more carbon than they have stored since 2001.

“There isn't any one technology that's going to do this,” Anex said. “We need afforestation. We need … enhanced weathering, we need this kind of stuff … We need them all.”

Investing in and scaling novel CDR technologies also comes with serious drawbacks. The capacity of novel technologies would need to double every five months by 2030 in order to fill the gap not met by conventional methods, Anex said.

Emily Grubert, a professor of sustainable energy policy at the University of Notre Dame and panelist at the November WEI forum, cautions that CDR technologies require huge inputs of energy and can be used as an excuse for further emissions.

“Looking at some of the global impacts and estimates of even fairly minimal CDR, we could maybe expect to be using about as much electricity as the entire world uses now just to power DAC [direct air capture] in some of these scenarios,” Grubert said.

Grubert said direct air capture technology can be beneficial when it’s used to abate emissions from industries that are difficult to transition from fossil fuels, such as the steel, building materials, and chemical industries.

Most direct air capture technology requires a liquid or gas to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The key element in the process involves “wringing out” the liquid or gas sponge, requiring massive amounts of energy.

Anex thinks he has a better idea.

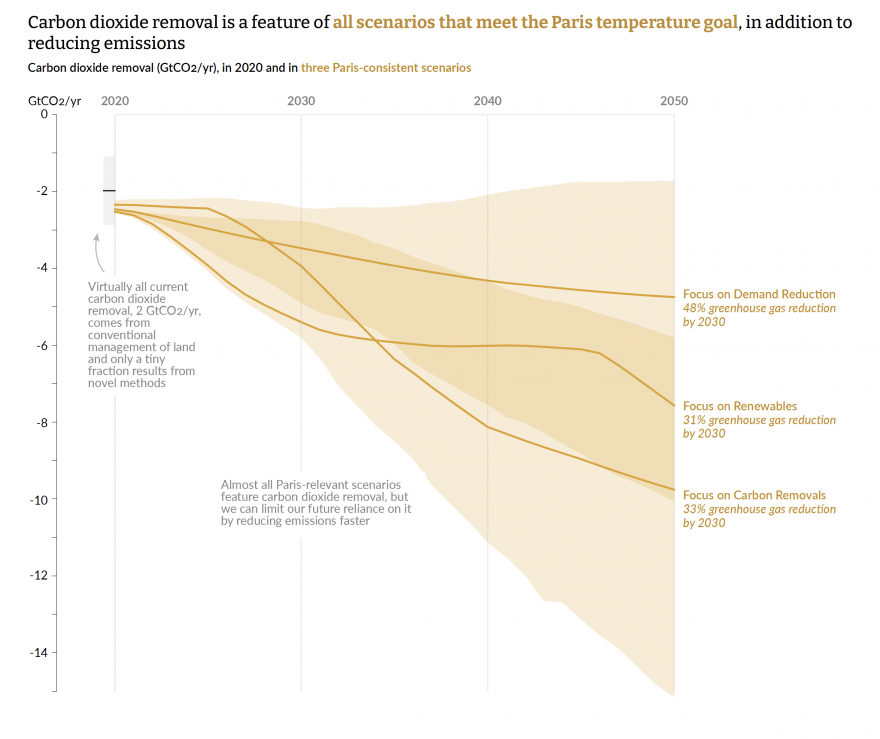

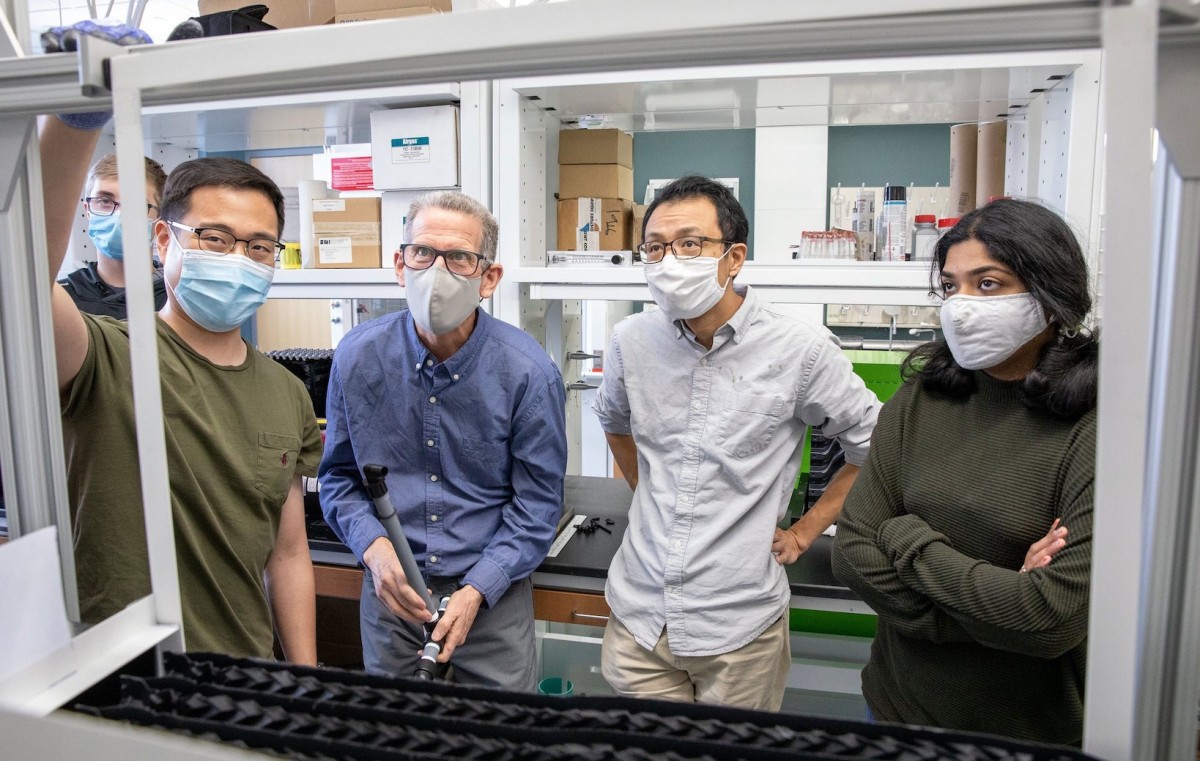

He and UW–Madison engineering professor Bu Wang developed technology that pulls carbon dioxide from the air to create a cement alternative. Cement is responsible for about 8% of the world’s carbon dioxide production. Anex said their spinoff company, Earth RepAIR, could have a plant in operation as early as 2026.

Current climate projections zero in on the year 2100. That’s over 70 years away, but the effects of climate change are being felt here and now, often by those who had very little hand in exacerbating pollution and climate change.

In her research, Bindl also accounts for the inequities associated with climate change. She asks questions like, “Are the ones historically responsible for carbon emissions cleaning up the mess?”

The World Health Organization reports that 3.6 billion people currently live in areas susceptible to climate change. The effect of climate change will disrupt food systems and affect the intensity and frequency of storms, hurricanes, and heatwaves. Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is predicted to cause an additional 250,000 deaths each year. These deaths will be from undernutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat stress. According to research cited by the World Health Organization, more than a third of heat-related deaths are caused by human-induced climate change.

The developing world is and will continue to face uneven consequences associated with climate change. But emissions reductions, supported in part by CDR, is what most experts understand to be the solution.

“While climate change can kind of be a rather dark and cloudy problem, when you think of it on its face,” Bindl said, “CDR offers kind of like a ray of sunshine or a little bit of opportunity to think about the positives that we do have a chance to reverse our situation.