A team of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has identified the genes and enzymes that create a promising compound — the 19 carbon furan-containing fatty acid (19Fu-FA). The compound has a variety of potential uses as a biological alternative for compounds currently derived from fossil fuels.

Researchers from the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC), which is headquartered at UW-Madison and funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, discovered the cellular genomes that direct 19Fu-FA’s synthesis and published the new findings Aug. 4 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

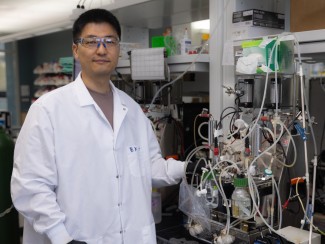

“We’ve identified previously uncharacterized genes in a bacterium that are also present in the genomes of many other bacteria,” says Tim Donohue, GLBRC director and UW-Madison bacteriology professor. “So, we are now in the exciting position to mine these other bacterial genomes to produce large quantities of fatty acids for further testing and eventual use in many industries, including the chemical and fuel industries.”

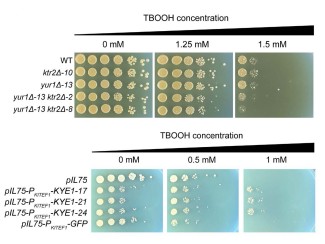

The novel 19Fu-FAs were initially discovered as “unknown” products that accumulated in mutant strains of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, an organism being studied by the GLBRC because of its ability to overproduce hydrophobic, or water-insoluble, compounds. These types of compounds have value to the chemical and fuel industries as biological replacements for plasticizers, solvents, lubricants or fuel additives that are currently derived from fossil fuels. The team also provides additional evidence that these fatty acids are able to scavenge toxic reactive oxygen species, showing that they could be potent antioxidants in both the chemical industry and cells.

It is not often that one identifies genes for a new or previously unknown compound in cells. It is an added benefit that each of these compounds has several potential uses as chemicals, fuels or even cellular antioxidants.

Tim Donohue

Cellular genomes are the genetic blueprints that define a cell’s features or characteristics with DNA. Since the first genome sequences became available, researchers have known that many cells encode proteins with unknown functions according to the instructions specified by the cell’s DNA. But without known or obvious activity, the products derived from these blueprints remained a mystery.

As time has gone on, however, researchers have realized that significant pieces of these genetic blueprints are directing the production of enzymes — proteins that allow cells to build or take apart molecules in order to survive. These enzymes, it turned out, create new and useful compounds for society.

“I see this work as a prime example of the power of genomics,” Donohue says. “It is not often that one identifies genes for a new or previously unknown compound in cells. It is an added benefit that each of these compounds has several potential uses as chemicals, fuels or even cellular antioxidants.”

A cross-disciplinary, collaborative effort between GLBRC chemists, biochemists and bacteriologists in departments at UW-Madison and Michigan State University yielded the chemical identity of the fatty acid compounds and identified the specific genes that direct their synthesis in bacteria.

“I don’t think this discovery would have been possible,” says Rachelle Lemke, the paper’s lead author and a research specialist in Donohue’s lab, “without the analytical and intellectual expertise of the members from this center.”