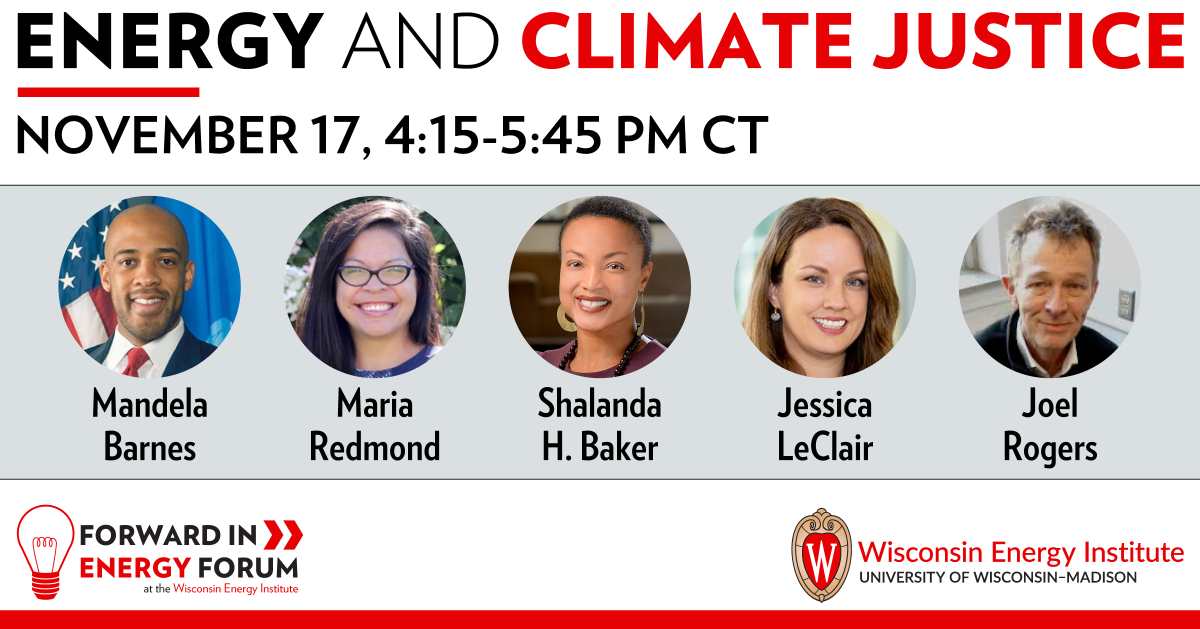

While climate change is a threat to us all, the effects of our warming planet have a disproportionate impact on communities of color and low income groups. Wisconsin Energy Institute’s next virtual Forward in Energy Forum on November 17, at 4:15 PM brought together climate justice scholars to address these issues toward establishing a sustainable, fair and equitable society. We sparked an email chain with three of our panelists to continue the conversation. Watch the whole event here.

What is climate justice, and what does it mean to you?

Maria Redmond, Director of the Wisconsin Office of Sustainability & Clean Energy: Climate justice is fully acknowledging and addressing the impact of climate change and adverse effects aren’t felt equally among all communities, and often intensifies existing social inequities. In Wisconsin, Indigenous, low-income and communities of color often bear the weight of negative impacts of climate change due to living in proximity to heavy emitters, in flood plains or near eroding coastlines.

Maria Redmond, Director of the Wisconsin Office of Sustainability & Clean Energy: Climate justice is fully acknowledging and addressing the impact of climate change and adverse effects aren’t felt equally among all communities, and often intensifies existing social inequities. In Wisconsin, Indigenous, low-income and communities of color often bear the weight of negative impacts of climate change due to living in proximity to heavy emitters, in flood plains or near eroding coastlines.

What this means to me is that as we deploy clean energy and explore sustainability, it’s imperative to develop the most effective, just and equitable clean energy policies and programs, while ensuring fair and meaningful involvement of frontline communities.

Jessica LeClair, UW–Madison School of Nursing Clinical Instructor: Climate justice is at the forefront of the environmental justice movement. As a nurse, I think about how within marginalized communities that are plagued by environmental racism, there are extremely physically vulnerable populations like people who are very young, very old, and living with chronic health conditions. These populations are most affected by disproportionate exposure to the effects of climate change and associated health issues.

Jessica LeClair, UW–Madison School of Nursing Clinical Instructor: Climate justice is at the forefront of the environmental justice movement. As a nurse, I think about how within marginalized communities that are plagued by environmental racism, there are extremely physically vulnerable populations like people who are very young, very old, and living with chronic health conditions. These populations are most affected by disproportionate exposure to the effects of climate change and associated health issues.

Climate justice is also connected with planetary health, which underscores that human health and human civilization depend on the health of natural systems. Climate change is only one symptom of multi-system failure of our planetary body, and is linked to other damage such as biodiversity loss, deforestation, ocean acidification, etcetera. Advocating for climate justice includes a transdisciplinary approach that partners with communities who are most affected to demand policy change and governmental leadership for planetary health.

How can we begin to incorporate climate justice more meaningfully into society? What steps do we need to take/policies do we need to enact change in this area?

Shalanda Baker, Northeastern University Professor of Law, Public Policy and Urban Affairs: Climate intersects with and cuts across every aspect of life, which means our laws and policies must meaningfully incorporate justice-based principles while also working to mitigate climate change. I'm thinking about the low-hanging fruit of energy policy, but also housing policy for low- to moderate-income folks and agricultural policy. To meaningfully incorporate climate justice into existing policies, we need vulnerable communities to have a seat at the policymaking table, as well as commitments from lawmakers to move substantial resources to these communities to help combat climate change.

Shalanda Baker, Northeastern University Professor of Law, Public Policy and Urban Affairs: Climate intersects with and cuts across every aspect of life, which means our laws and policies must meaningfully incorporate justice-based principles while also working to mitigate climate change. I'm thinking about the low-hanging fruit of energy policy, but also housing policy for low- to moderate-income folks and agricultural policy. To meaningfully incorporate climate justice into existing policies, we need vulnerable communities to have a seat at the policymaking table, as well as commitments from lawmakers to move substantial resources to these communities to help combat climate change.

One example of both things is happening in New York where, through the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act the state is convening an environmental justice working group to help determine how to allocate the 40% of overall climate spending for frontline communities spelled out in the Act.

LeClair: When I think about critical next steps for climate justice policy, I believe we must shift towards applying the lenses of environment, health, and equity in all policies. Climate change, health inequities, and other social and environmental injustices share the same root causes, and we cannot afford to address them separately. It would be ideal to see more collaboration between the separate committees, task forces, and/or planning efforts.

Climate change and other environmental injustices heighten health and social inequities, and the processes of injustices are inextricably linked. It’s no coincidence that communities that are already worn down by racism and environmental injustices experience worse health outcomes with COVID-19. Powerful institutions are influenced by racism and shape the conditions where we live, learn, work, and play. Many of these institutions are also major drivers of climate change and environmental degradation.

The opportunities for synergistic solutions through collaboration are great. Strategies that address racism and other social determinants of health to reduce health inequities will also increase climate resilience.

Redmond: As a government employee currently working on a plan to move towards a clean energy economy, it’s abundantly clear that a major missing piece to policymaking is ensuring frontline communities are actively involved in the process. Some steps that need to be taken include education — especially in government bodies — of what climate justice is and why it’s important. We need to evaluate our programs/processes to identify socioeconomic disparities.

Then as we begin to develop policies, we need to stay true to and act upon meaningful inclusion in that process. And then, as we move forward, ensure subsequent allocation of technical expertise and resources to support and implement change.