Research aims to produce valuable chemicals from manure

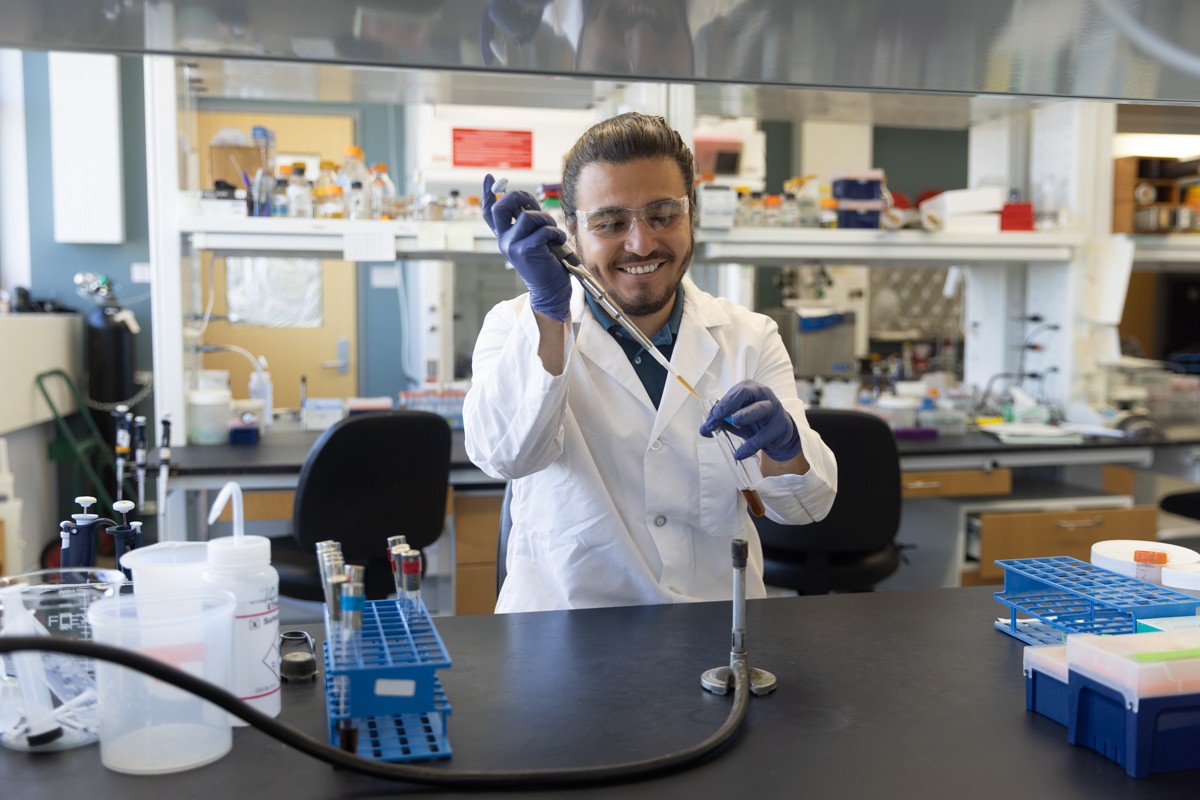

Brayan Riascos Arteaga is a third year PhD student in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering. He works in the Noguera lab, where he’s developing ways to utilize manure fibers as a lignocellulosic resource.

Tell me a little about your research

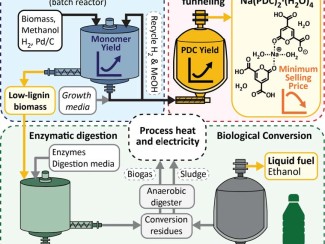

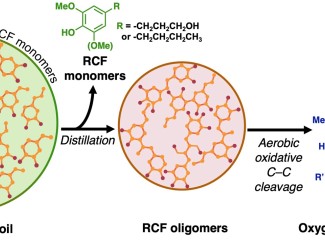

My research project is focused on how to harness and utilize post-anaerobic digestion manure fibers as a lignocellulosic resource for the production of target products that are currently produced from crude oil or petroleum. We are currently trying to produce PDC, which is a precursor for plastics and polyester materials. Hopefully in the future we will also try to produce ccMA (muconic acid), which is a precursor for nylon. The goal is to provide a more sustainable alternative to plastics made from oil.

How is your process more sustainable than oil based plastic production?

Nobody can deny that the easiest way to make plastic is from oil. It's been developed for decades. We are still trying to produce those plastics from plants on a bench scale, but if the technology and the microbial processes are fully developed in full scale industry, we could get some numbers to finally compare the amount that we could produce from renewable resources. But manure fibers are a really abundant residue that’s pretty much everywhere in the world. Many people in the world eat beef and dairy. So there's plenty of manure fibers to use: I'm talking about millions of tons.

What does your work look like?

You start with manure fibers.They look like soil or compost. You pre-treat that biomass to extract the lignin, which is what you feed the microbes to produce PDC. We use Novosphingobium aromaticivorans, a strain that has been engineered by former students in the Donohue and Noguera labs. It takes all the aromatics from lignin when you pre-treat the biomass — in this case manure — and it funnels all those components into one single product, which is PDC. PDC is an intermediate in its metabolism, but former students modified the strain to accumulate that intermediate.

What’s your favorite part of your job?

I like the moment I treat the biomass because I see how beautiful it is when you have a residue that nobody cares about. You say “manure” to anyone and they think it’s gross. And when I have one pound of that and I start doing the biomass per treatment to get a liquid full of aromatics, I see on a small scale the transition of a residue into a really valuable product.

Tell me a little bit about your academic path, how did you end up involved in this research?

I studied environmental engineering at an undergraduate level in Colombia. I always had a dream of studying at a graduate level, but I had economic limitations so I needed to get resources from scholarships or fellowships awards. I got a scholarship to pursue a masters in environmental science in Spain. After that, I worked a little bit in Colombia in my professional field, and then I applied for another scholarship. It's called EducationUSA Opportunity Funds, which is a scholarship that is powered by the U.S. Department of State, plus the U.S. embassy in Colombia. That scholarship helped me to apply to several universities in the U.S. Out of all those universities, I got an offer from Professor Noguera at UW–Madison and I said, “This is my place.”

That's what I love about science. You always ask questions from a really humble standpoint. You try to improve things for human beings, for the world, from a tiny bench.

Brayan Riascos Arteaga

What do you like about working at WEI?

I like that people are always willing to offer a hand. If you’re stuck or you have questions in the lab, anyone is willing to help with anything. It’s a good environment for work. Also, the WEI is a beautiful building. I love the views. Sometimes when I'm working at 7 or 8 PM in summer, I see the sunset. So that kind of charges me when I’m getting tired at the end of the day.

What advice would you give to someone who wants to get involved in research?

The most important thing to me is feeling interested in always learning every day. No matter if it's a tiny thing that you learned or a big topic, or whatever, it's really beautiful to start every day by feeding your brain, your thoughts, your mindset. I think it makes you more humble, a more sensitive person, a more prudent person, and I think that's what I love about science. You always ask questions from a really humble standpoint. You try to improve things for human beings, for the world, from a tiny bench. Look for things that make you curious and never overlook what you're doing or its contribution to the world.

What do you do in your free time?

I am a percussionist and I play several types of music, but I would say mainly pop, rock and roll, and Latin music. My band is called Orchestra SalSoul Del Mad. It’s a combination of two worlds: American pop songs and rock and roll, with the Latin world, salsa and Afro-Cuban and Caribbean rhythms. I play with them in my free time, mainly in the summer. The summer opens up a lot of events and games. I've been playing music for twelve or fourteen years. It's a big part of my heart.

Do you feel like there's any overlap between music and what you're doing here? Or a way that music makes you think differently about research?

There is one thing that I always recall when I'm in the lab. In both music and science, you really have to be patient. You have to understand that the learning curve can be really long and really frustrating, but at the end you'll see the results. When I was a teenager practicing drums, it took me years and years to finally see the results in my performance. It’s the same thing in science. Many experiments won't work and those will make you feel so frustrated. That’s where patience needs to rise up. I always try to calm down and understand that those things happen, and to understand that at the end I will see the results, but I need to work hard to understand the bad results.

Is there anything else that you want people to know about your life or your work?

Trust people that are trying to create solutions. Remember that nature offers us ways to do things more sustainably. Cows produce millions of tons of residues. Let's do something with that. Secondly, if anyone is interested about what I'm doing, feel welcome to come over and talk to me. I'll be happy to show what I'm doing with the manure fibers, with the biomass treatment, with the bioconversion experiments, batch tests, and bioreactor experiments. I'll be more than happy to show you what I'm doing and that maybe eventually might become a new technology.

What’s your hope for the future?

My dream is some day visiting a facility where there's a huge pile of manure, digested manure. Some people are putting that manure into a reactor to take the lignin from it, another bioreactor with microbes inside, and another giant vessel with the PDC ready to go. I don't care if that's patented or not. I don't care if I'm not there. I just want to see that something is happening. I'm not changing the history of the world, but just contributing with a tiny piece to solutions to climate change.