A 61-acre property along the Elizabeth River may soon become a complex with technology straight out of the 1980s movie “Back to the Future.”

The proposed facility promises to turn household garbage into diesel and wax much like how Doc Brown used trash to power the DeLorean time machine.

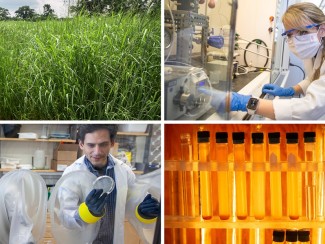

The Hampton Roads Integrated BioEnergy Complex would turn materials like plastic and rubber into products used to make a water-resistant coating and cosmetics or a cleaner diesel fuel.

The City Council voted 8-1 on June 18 in favor of granting a conditional-use permit for the new project to move forward off Bainbridge Boulevard. It was the same margin under which a similar proposal passed in 2016.

The sprawling space where the main facilities would be located has been home to an eyewear company and various chemical operations.

But its location just south of the High Rise Bridgeon the eastern side of the river has raised some concerns about the environmental impact.

Debbie Ritter, the one council member who voted against approving the permit both times, said she was worried that the facility would be handling waste in an “environmentally sensitive area.”

Joe Rieger, the deputy director of restoration at the Elizabeth River Project, a nonprofit focused on keeping the river clean, said the location of the complex so close to the water is the troubling factor, not the work being done inside. The river is home to aquatic life that could be threatened if there were a spill that contaminated the Southern Branch, he said.

“Our concern is that during a storm or just long-term with sea level rise, this site might not be accessible to emergency response,” Reiger said. “Even though most of the facility is out of the floodplain, a lot of the low-lying area around it wouldn’t be accessible.”

But the company's plan could benefit the environment in other ways.

Timothy Donohue, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor and expert on renewable energy technologies, said that while the field of bioenergy has been around for about a decade, the Chesapeake facility might be a trailblazer in how it reuses household garbage.

“Right now that garbage goes into a landfill, and it doesn’t do much for society,” he said. “Why not take something that we have a lot of and convert it into profitable materials?”

Reclaiming waste

The project started almost five years ago when Ray Crabbs, the founder and CEO of the renewable energy company responsible for the proposal, set out to find a long-term solution to deal with Hampton Roads’ trash.

The group Crabbs assembled at the time included RePower, an international energy company that had intended to work with the Southeastern Public Service Authority to turn the garbage they collect from South Hampton Roadsinto fuel.

The City Council approved this project in January 2016. But when RePower failed to secure a buyer for its fuel and funding fell through, SPSA withdrew its contract with RePower and Crabbs was forced to re-evaluate.

His company picked up where RePower left off with the Hampton Roads Integrated BioEnergy Complex, but made several changes to the proposed project.

RePower’s plan had been to take municipal waste with fibrous content like fabric that couldn’t be recycled and compress it into fuel pellets, said Pete Burkhimer, a civil engineer whose company, American Engineering, has been working on the project for five years. The pellets would then be burned with coal to produce cleaner emissions.

Under that plan, RePower would have been left with about 35% of the SPSA waste that could not be converted to pellets, and those materials would have ended up in the landfill.

Crabbs' new proposal aims to use 95% of the garbage brought in by private trash haulers.

“We think we’re going to do better than that,” Crabbs said.

The product the company plans to make, however, will not be fuel pellets. Instead, the new facility would convert garbage to wax and clean diesel fuel.

The facility’s machines would take anything carbon-based like plastic and rubber and turn it into synthetic natural gas.

That gas would then be passed over a catalyst, like cobalt, that causes hydrogen and carbon monoxide to bond together in longer hydrocarbon chains to produce FT wax, a type of synthetic used to make cosmetic products as well as water-resistant coating for cardboard boxes to protect them from the rain after delivery.

Another product of this method, called the Fischer-Tropsch process, would be “excellent quality diesel” that runs clear instead of amber, according to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Scientific and Technical Information.

“Our diesel has no sulfur at all,” Crabbs said. “It’s a very pure fuel.”

That product could be helpful in cutting sulfur oxide emissions from ships, even if it’s only blended with classic diesel.

Glass products, on the other hand, would be turned into mineral wool used for insulation, Crabbs said. Other waste products would be used for green energy, ensuring that the facility keeps its promise to put most of the trash to use.

Donohue, who also is director of the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center at UW-Madison, said his research focuses on generating fuel from plant matter as opposed to non-natural materials. But he has colleagues who use the Fischer-Tropsch method and other approaches to achieve goals similar to Crabbs’.

“In my mind, it is one of a large number of activities that could help us diversify how we produce fuels and chemicals for society moving forward,” he said.

Changing landscape

The land at 5100 Bainbridge Blvd. intended for the bioenergy buildings has been home to a host of companies, but eventually the chemical producers moved out and the bioenergy company bought the property in 2015.

Foster Grant, an eyewear company, first owned the land in 1972, but sold it to chemical manufacturing company American Hoechst in 1978.

That sale kicked off a trend of chemical companies occupying the space, including Huntsman Corporation, NOVA Chemicals, and current tenant CHEMRES, which produces medical-grade plastics. CHEMRES will remain on the property when the bioenergy complex opens.

While the Elizabeth River Project is primarily concerned with convincing the City Council to consider policies restricting development on low-lying land, it believes the proposed process for handling waste will benefit Hampton Roads.

“This project has been approved and there’s going to be many other projects like this in the future,” Reiger said. “What we’re trying to do is have Chesapeake work on limiting projects in these flood-prone areas.”

Crabbs' company has been working with the Elizabeth River Project for three years. He has agreed to place a plot of land north of Interstate 64 and the High Rise Bridge into a conservation easement held by the Living River Restoration Trust. So while the bioenergy company would retain ownership of the property, it handed over the rights to the land to limit future development.

The company has also made connections with Tidewater Community College and Old Dominion University to discuss the possibility of having a STEM research center in the complex.

“The presence of Tidewater Community College on this site … would offer not only a natural learning laboratory for our students to learn firsthand about biofuel production, but also ingrain them in a wide-ranging vision of sustainability,” said James Edwards, the interim provost of TCC's Chesapeake Campus.

Crabbs told the City Council he’s been making an effort to develop relationships with other organizations in the area so the bioenergy complex can affect positive change.

“One of the things that has been critical to us over the four years we’ve been in discussions with the community is how we fit as a neighbor into the fabric of the community of Chesapeake and the broader region of Hampton Roads,” he said.

This also means making the main office building facing Bainbridge Boulevard look presentable — more like a tech start-up and less like a manufacturing plant — and providing jobs to Chesapeake residents.

Crabbs said he hopes to employ a range of people, from military veterans to former prisoners, looking to rejoin the workforce.

Now that the City Council has approved the project, the state Department of Environmental Qualityhas to issue a certificate for solid waste handling. But Crabbs said that’s a “relatively perfunctory” process and he hopes the entire facility will be up and running in about 2½ years.

By then, instead of looking at construction vehicles, abandoned buildings and neglected grass on the site, passersby could catch a glimpse of a greener future.