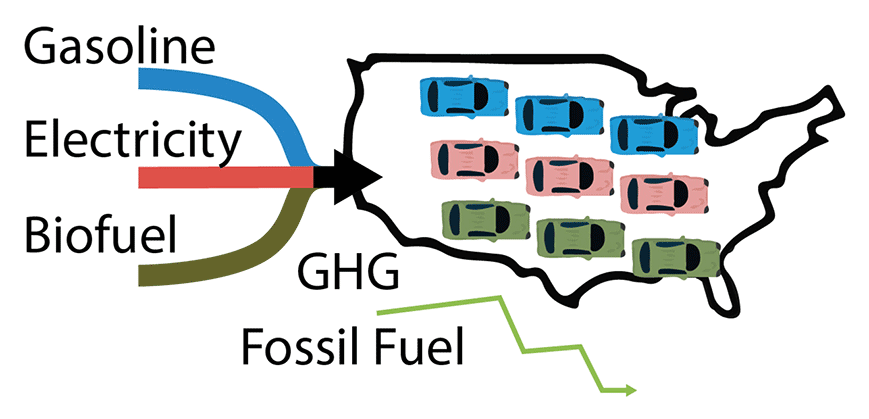

What will it take to make a cross-country drive in a light duty vehicle, the kind of car or truck many of us drive every day, a low-carbon pursuit?

According to Wisconsin Energy Institute (WEI) scientist and modeling expert Paul Meier, it will take a combination of three advances: a large increase in the adoption of electric vehicle use, a huge uptick in biofuels production, and a change in the habits of U.S. drivers.

In a recent study, Meier and collaborators from the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) developed a number of light duty vehicle use scenarios that could reduce U.S. consumption of regular unleaded gasoline by 50%.

“The goal of making the U.S. entirely energy independent has been an aim of U.S. policy since the 1970s,” says Meier. “That 50% benchmark was intended to serve as a proxy for energy independence, as it’s roughly the amount of petroleum the U.S. has historically imported from foreign sources.”

The team also crunched the numbers to see how the U.S. can reach another crucial milestone: reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions into the atmosphere by 80%. That number, cited in President Barack Obama and Vice President Joe Biden’s 2014 “New Energy For America” plan, represents a “good citizen” benchmark that could make the U.S. a leader in minimizing the global impacts of climate change.

It’s notable that only the scenarios calling for high or moderate adoption of both electric vehicles and advanced biofuels met the emission goals.

Paul Meier

The greenhouse gas reduction was ultimately the more difficult target. Out of the 27 scenarios the team ran, eleven achieved close to a 50% reduction in gasoline, but only three projected a pathway to meet an 80% reduction in emissions by 2050.

“It’s notable that only the scenarios calling for high or moderate adoption of both electric vehicles and advanced biofuels met the emission goals,” says Meier.

The projections assert that cellulosic biofuels production needs to play a major role in reaching U.S. emission goals by 2050. “16 billion gallons of advanced low-carbon biofuels was the minimal contribution by which we projected meeting emission goals, and those conditions required no growth in travel demand and 40% electrified transport powered by clean electricity,” says Meier.

While the Environmental Protection Agency recently scaled back the amount of cellulosic ethanol it plans to incorporate into the U.S. fuel supply, Meier says more aggressive biofuel projections would meet emissions targets even with ongoing growth in travel demand or lower adoption of electric vehicles. Research by study co-author and GLBRC scientist Bruce Dale, for example, reveals that more concerted efforts could achieve over 100 billion gallons of renewable ethanol production.

Another key component of the models is the importance of behavior change. With the exception of periods of recession, however, vehicle miles in the U.S. have steadily increased at a moderate rate, slightly less than 1% per year.

“The difference between a low and moderate increase in vehicle miles might not seem like much, but it adds up fast over the course of a model ending in 2050,” says Meier. “Success in these scenarios becomes more practical if we were to drive less and shift toward mass transit or other means of transportation, taking cars off the road on a day-to-day basis.”

While the study suggests that the road to cleaner transportation will be challenging, it also provides a detailed roadmap for reaching U.S. emission goals.

“The takeaway here is that these target reductions are possible,” says Meier. “These scenarios tell us how we can get there.”