Given the shouts and cheers emanating from Lisa Andresen’s classroom, one might guess that Room 105 doubles as the school’s gym. In fact, these are the sounds of middle school students exploring energy and environmental science.

Andresen, an educator for more than 10 years, is teaching science in the North Crawford School District in southwestern Wisconsin for the first time this year with the help of two educator institutes she attended this past summer at the Wisconsin Energy Institute at the University of Wisconsin–Madison: the five-day Bioenergy Institute for Educators (hosted by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center) and the three-day Energy Institute for Educators.

The institutes provide educators with the opportunity to learn about UW–Madison’s cutting-edge energy research and return to their classrooms equipped with new strategies and materials for incorporating energy science fundamentals into their own curriculum. Since the teacher institutes began, 84 Wisconsin educators — teaching an estimated 5,000 students per year — have participated.

“I arrived with absolutely no idea what I might teach in my science class, and attending both the workshops gave me a foundation,” Andresen says. “I came home with a very clear plan to start my students out by asking the fundamental question, ‘What is energy?’ and to advance from there.”

Andresen’s students, who range from 6th to 10th grade, are now engaged in a hands-on energy and environmental science curriculum that keeps them excited, active and learning.

In the fall, the students spent several weeks studying solar energy in order to design and build solar ovens they used to bake chocolate and caramel pretzel treats on the school’s front lawn.

“There was a lot of traffic in and out of the school that day,” Andresen says, “which created a great opportunity for the kids to share treats, answer questions, and tell the school community all about their different oven designs and the science behind them.”

“It was pretty cloudy that day,” one of Andresen’s students remembers, “but during the summer I’m pretty sure I’ll be cooking my lunches in that oven.”

Using institute lesson plans on biodiversity sampling and root depth in biofuel crops such as prairie plants, Andresen’s students next launched a study of local biodiversity and sustainability.

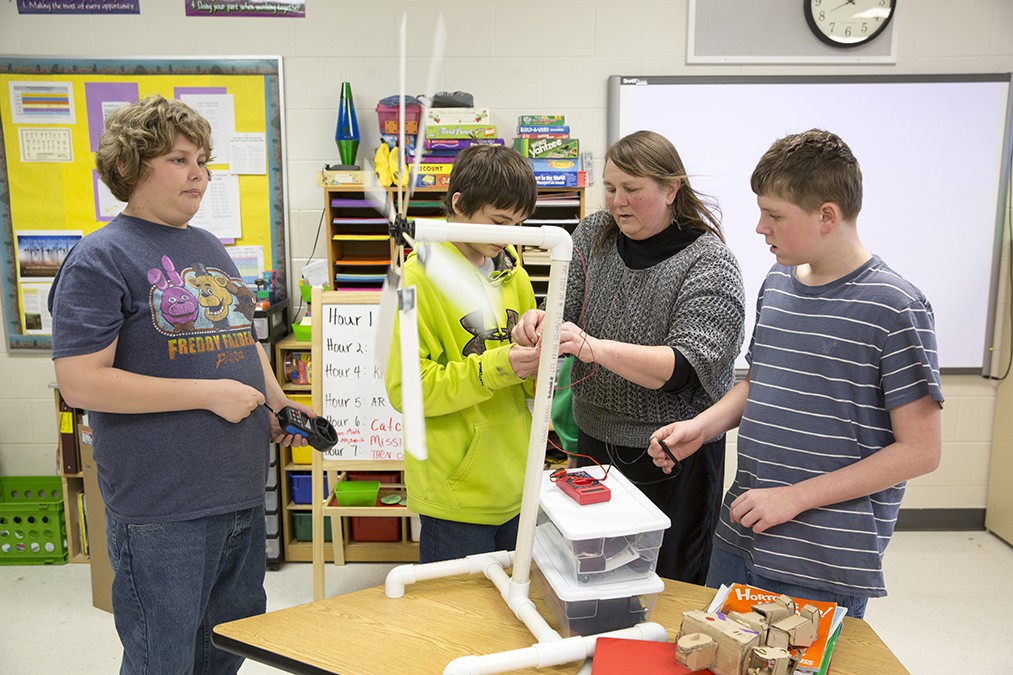

With PVC pipe, the students built quadrats — square frames used in ecology research to create a boundary around a plot of ground — to explore the diversity found in their own quiet valley of Wisconsin’s driftless region.

“We took our quadrats to a few different places,” a student explains, “the school’s front lawn, the roadside and a prairie. We took pictures of all the plants in the quadrat and used them to estimate different amounts of different plants in the ecosystem.”

“These kids live in farm country, among lots of corn fields,” Andresen says, “so they know about biofuels and understand the concept of a monoculture. Even so, they were truly surprised by how much more plant diversity they found in the prairie compared to the roadside and the lawn.”

Talking over one another, Andresen’s students catalog the benefits of prairie plants. “They are really good at holding the ground together,” one student says. “When a prairie plant dies its long roots break down and make the soil more fertile,” another chimes in.

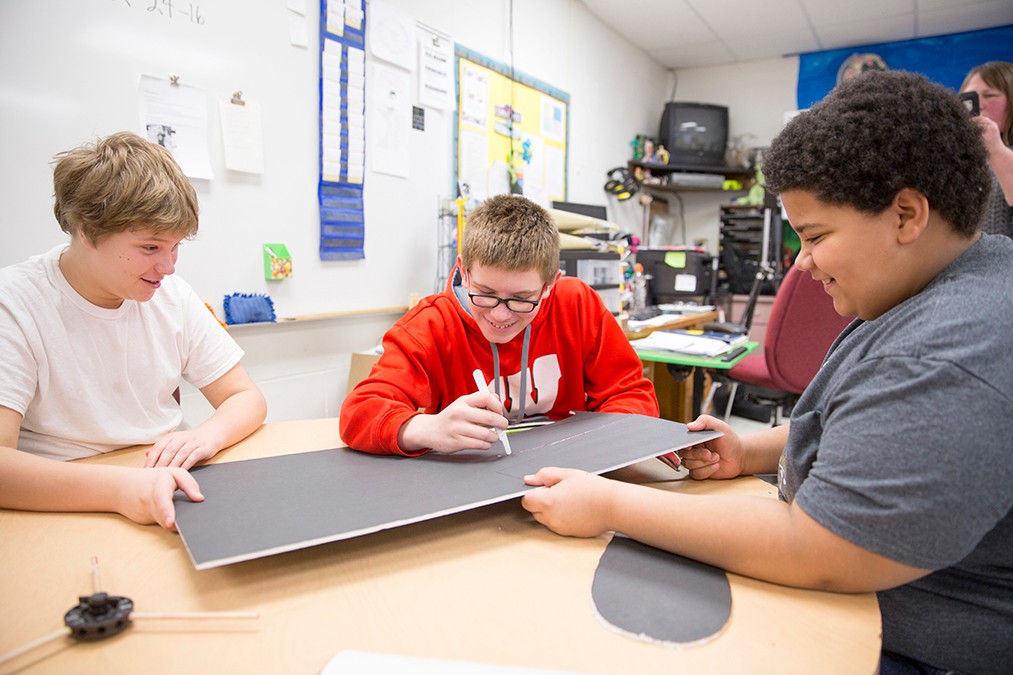

The animated conversations in Andresen’s classroom have most recently shifted to wind speed, aerodynamic stability, lift, and drag as the students are now designing and building wind turbines to compete in an online KidWind Challenge. As students cut foam board with X-Acto knives, mount blades on hubs, and measure blade angles, a heated debate takes place about the pros and cons of slender quadrilateral blades versus broad rounded blades like those on a tabletop fan.

“Kids learn best with hands-on activities, really getting in there and understanding how things work,” Andresen says. “I learned so much about energy science at the institutes last summer and came home full of ideas and binders full of lesson plans and experimental guidelines that help me teach science in an active and meaningful way.”

“It’s inspiring to see what Lisa has done with her students this year,” says Leith Nye, outreach and education coordinator at the Wisconsin Energy Institute and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center. “But it’s also gratifying to be reminded of how these institutes are reaching students all over Wisconsin.”