Jevons Paradox predicts that improvements in energy efficiency lead to overall increases in use.

As some of the world’s best thinkers work to engineer cleaner, more efficient forms of power, there’s one particular limit University of Wisconsin–Madison's Giri Venkataramanan believes is essential to remember: Jevons’ Paradox.

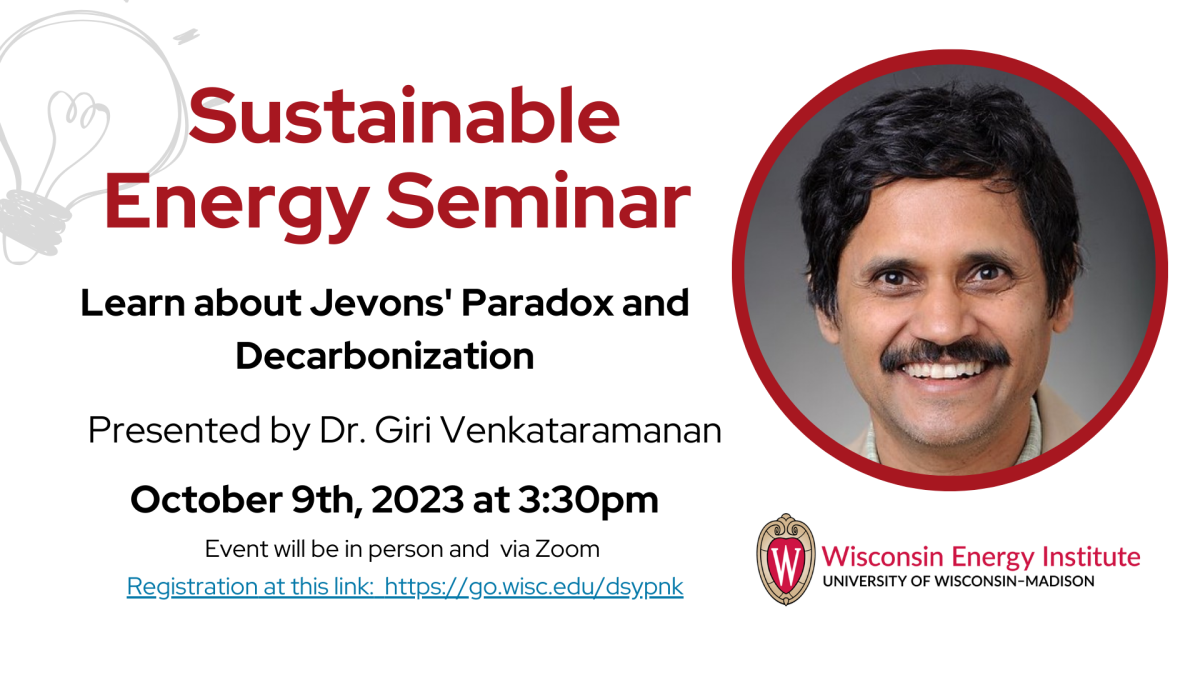

Venkataramanan, Keith and Jane Nosbusch Professor in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, will discuss how this 158-year-old economic theory relates to the challenges of fighting climate change in an Oct. 9 seminar hosted by the Wisconsin Energy Institute (WEI).

Nineteenth century English economist William Stanley Jevons may not have foreseen today’s energy landscape, but his legacy informs it.

Jevons’ Paradox highlights the unintended consequences of energy innovation. As new, more energy efficient technology emerges, access increases and overall consumption increases. Though energy sources may be cleaner and more efficient, more people buy them, narrowing the decarbonizing effect of more efficient forms of energy.

For example, modern LED bulbs are about seven times more efficient than incandescent lighting. But “the amount of electricity used for lighting is only going to grow,” said Venkataramanan. It’s the same concept with 5G. It’s more efficient, but now more people than ever are streaming.

In order to avoid the most devastating impacts of climate change, scientists say the world needs to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by the end of this decade and eliminate them completely by 2050. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, that means replacing fossil fuel generation with cleaner sources of electricity like wind and solar, but it will also require gains in energy efficiency to lighten the load on the grid.

As an electrical engineer, Venkataramanan understands that the way forward is through clean energy. The wind, solar and transportation applications of power electronics have occupied Venkataramanan for decades, but he believes it's important to sensitize others to the lessons of the past.

“History indicates that the performance improvements have been absorbed up by increased demand, and do we have sufficient reason to believe the clean energy transition would be any different?” Venkataramanan reflected. “We expect to decarbonize, but … if we think that we’re going to decarbonize and reduce our energy consumption because of improved efficiency, we’re not paying attention.”

Venkataramanan believes that engineers and scientists can’t offer a “silver bullet solution.”

The issue of consumption is one that individuals will have to reckon with on their own. Two ways to support this reckoning are through role-modeling and discourse. According to Venkataramanan, modern day living is saturated with electronics and energy consumption. At some point, individuals have to find the limit.

Venkataramanan, who studies electricity systems, building efficiency and microgrids, received his Ph.D. from UW-Madison and returned a few years later as faculty in 1999. He was first exposed to Jevons' Paradox in the 1990s.

It was people such as John Muir, Aldo Leopold and Frank Lloyd Wright that motivated Venkataramanan to return to Wisconsin. And it is these thinkers that inform his work to this day.

“We have to dig deeper and not be satisfied with improving the efficiency,” he said. “If we want to make the world a better place what do we need to do?”

Venkataramanan's lecture will be held in the WEI building at 1552 University Ave. at 3:30 p.m. on Oct. 9. All are welcome to learn about Jevons’ Paradox and its implications in person or online.

Scott Williams, the WEI’s research and education coordinator, explained that these seminars are designed to reflect the breadth of UW-Madison’s interdisciplinary energy expertise.

Williams hopes Venkataramanan's seminar will encourage people to take a step back and reflect.

"If we are not thinking bigger picture," Williams said, "we may miss something that’s ultimately more sustainable."