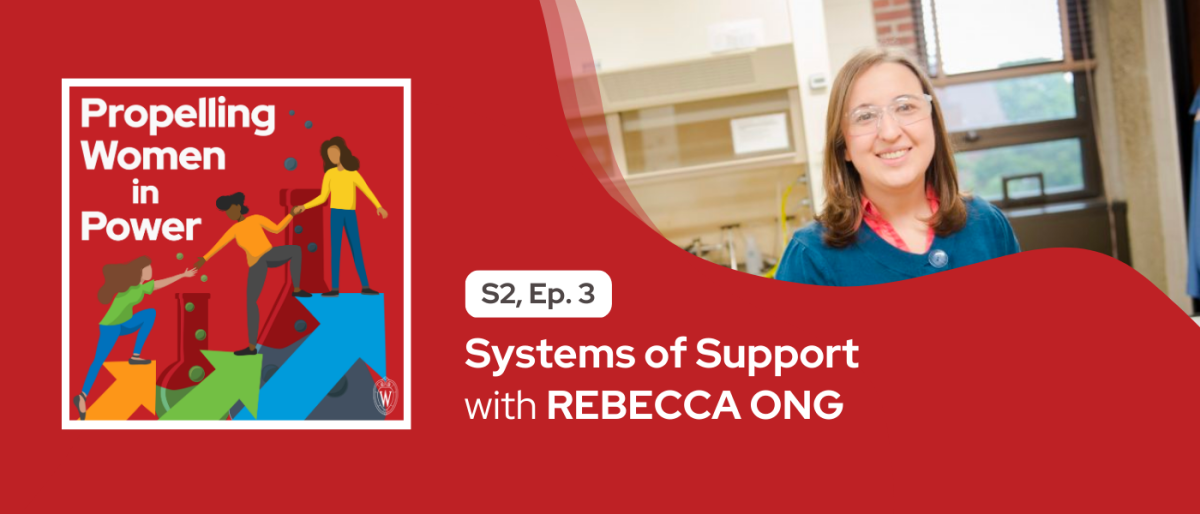

This week we sat down with Rebecca (Becky) Ong, Director of Graduate Programs and Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at Michigan Technological University, as she shares her journey from her childhood love of plants to her groundbreaking research converting them into biofuels. As she walks us through the institutional barriers that women face in academia, Becky discusses her experiences as a partner, parent, and professor and how systemic actions such as equity raises and high childcare costs impact these identities. She shares valuable insights into how academia can better support and empower women in STEM, including her work with a group of majority men advocating for their women and gender diverse colleagues and thoughts on how access to STEM education and representation should start in early childhood.

Listen on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Youtube, anywhere you find podcasts or listen below!

Links:

Advocates and Allies Advisory Board (A3B) at MTU

Ong Research Laboratory Website

Transcript

Meg Riker: The argument for institutional support versus grassroots support for anyone with a marginalized identity has been going on for a long time. In my opinion, grassroots support is necessary and a Kickstarter for any sort of change, but it must be followed by institutional support. In listening to many of our interview use. It seems like institutional change is a major barrier for diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives.What does and could institutional support really look like?

Michelle Chung: Our next guest, Dr. Rebecca Ong, gives us insight and answers to these questions on institutional support for partners, parents and professors.

[MUSIC]

Meg Riker: From the Wisconsin Energy Institute and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center. I'm Meg.

Michelle Chung: And I'm Michelle.

Meg Riker: And you're listening to Propelling Women in Power, a podcast about the careers of women in energy at the Wisconsin Energy Institute on the UW Madison campus and our sister institution, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center.

Michelle Chung: Let's dive in with Dr. Rebecca Ong.

Rebecca Ong: I am Dr. Rebecca Ong. Pronouns are she/her. My position is Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at Michigan Tech.

Meg Riker: So could you tell us a little bit about your research and what excites you the most about your work?

Rebecca Ong: Okay, so I have two main research areas, Both of them focused on sustainable issues in the world. So the first one is focused on converting lignocellulosic bioenergy into transportation fuels. And what does that mean? So lignocellulosics are things like grasses and trees and they have energy within them. And what we're trying to do is break them down and convert them into a liquid that we can then use to replace a fuel like what you put in your car.

The second area that I work in is on deconstruction of waste plastics. And so waste plastics are a huge concern They're accumulating in the environment. We're trying to find a way to break them down and turn them into something useful through a process called upcycling, where it has a higher value than the waste that we started with. So we're using a combination of chemistry and biology to try and do this, make something useful at the end.

I'm excited to do something that's useful for the world and for people in general. And so both energy and managing our waste are both really critical issues for the whole world globally. And so I'm excited that I get to contribute in a small measure to solving those problems.

Meg Riker: Could you talk a little bit about when you first became interested in these kinds of problems and chemical engineering and like, was there a specific moment when you knew you wanted to be a chemical engineer or did it kind of evolve over time?

Rebecca Ong: Okay. So I first became interested in sustainability because my parents are both foresters, and so conservation of resources has been a key part of forestry for decades. So my mom instilled that in me from a young age. So we were recycling when I was growing up. We were conserving our resources that we had available. And so that's always been a key part of what I did.

When I went to undergrad, I started a recycling collection in my dorm hall, and then I would actually take that and drive it to the collection site because we didn't have recycling facilities on campus. So that's always been important to me. Chemical engineering was a gradual thing. So when I when I was looking for for what I wanted to do in college, I had no idea.

I knew I liked math and I knew I liked chemistry and science in general. And so I came and I visited Michigan Tech, where I'm working now, and got to meet with a professor who told me that, oh, engineers are people who solve problems and I'm like, I like solving problems. And what that means is you're not just solving math problems or equations, but you're actually solving global problems as well.

And so I get to be part of that. So I came here as a general engineer because I had no idea what the different options were. And I got to learn a little bit about the different types of engineering and chemical was the one that resounded the most with me personally, just because of the types of information that you need to know and the types of things that you get to do.

Meg Riker: It's really cool that your parents are foresters. Like in a specific part of the Midwest or like where?

Rebecca Ong: I grew up in Michigan, so Michigan almost my whole life, except for a short time in Hong Kong, which is an interesting story. But yeah, so my mom was the first woman forester employed by the state of Michigan in the upper Peninsula of Michigan. And that's actually another reason why I went to the area that I did, because I have also had a love for plants, partially for the same reason with gardening and just my parents background.

And so when I came to Michigan Tech for undergrad, I got a degree in chemical engineering and at Green Plant biology, which is a very unusual combination, but it fits my research area very well. So it gives me an interesting perspective on bioenergy.

Meg Riker: Did you have any mentors aside from your parents, and who were they and what role did they play in your success to become professor in chemical engineering?

Rebecca Ong: So I think a lot of my mentors were sort of indirect. They weren't people that it necessarily spoke with about things, but people who I observed the way they lived and the work that they did that inspired me to go the direction I've gone. And so I had a number of women faculty in particular who were really, really intelligent, really good teachers, really no nonsense, and who really cared about the students who and I saw what they did.

And I had an opportunity to teach a little bit in undergrad and I was like, I love this. This is great, and I want to go into academia so that I can do the same thing. And so that's really why I went to graduate school was because of just seeing people doing what I wanted to do and wanting to do the same.

Meg Riker: I like that idea of an indirect mentorship. The first time I had a conversation with the other co-hosts about mentorship, I was like, Oh, like my friends are some of my best mentors. So our boss at the time, he was like, Oh, I never thought of it that way. It's like, Yeah, like our friends can be our mentors to the people that we don't traditionally think of.

Mentors can actually have a really big role on what we want to do. I think it's cool that you found that in your academic experience. So you have been a part of the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center since 2006, which is basically, as Michelle was telling me earlier, like the inception of GLBRC And that you kind of brought GLBRC to Michigan Tech.

So I was going to ask you, how did being a part of diversity influence your career and what was it like bringing it to another institution?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah. Oh, GLBRC was amazing. It was this amazing opportunity to get dropped into interdisciplinary research so it never would have happened without the GLBRC. And some of my what I consider to be my best work came about because we're working with people from a lot of different disciplines, from agronomy and chemical engineering and microbiology, and we all come together and we work on these problems that an individual researcher can't really solve easily because it's just such a big experiments are huge, they're massive, they're multi-year projects.

They take a lot of people and a lot of input to actually get them pulled off. And so being part of that has both inspired new research directions. Like one of my favorite projects that we came up with has inspired the research direction for my lab when I came here and when I got to be part of the new center.

So we're looking at how environmental impacts on the plants in the field carry through the whole bioenergy production process to influence the microbes as they're making fuels. No one's looked at this because it's such a big issue, right? You need to follow everything from the planet in the field all the way through the entire process. It's multistep takes a lot of effort and so no one's done this.

And so we've come up with some really good results from this work. And it's inspired a lot of people and a lot of different investigations from different labs within the center as well. It also boosted my confidence. So through the GLBRC, I became more confident in asking questions in the middle of talks, like people would give talks at the annual science meeting.

And I'm up there and I'm like asking questions and I'm answering questions because sometimes my advisor didn't know how to answer questions about from the plant biologists. And so I'd speak up and answer those. And so it's just a great opportunity to grow, build my confidence and grow my research areas.

Meg Riker: So something I wanted to ask you about what you talked about there was you said it's a multistep process that's very interdisciplinary.

Rebecca Ong: Yeah.

Meg Riker: Do you think in academia it's more difficult to have these kind of or easier than an industry to have these kind of interdisciplinary research and work based on the levels of funding that exist and the hierarchies and the institutional structures that are in place at universities versus in industry.

Rebecca Ong: I think it's actually easier an industry likely because people are typically put on interdisciplinary teams. You're not usually on a team with a single discipline, so you're getting perspective from different areas. I think in academia it's a lot easier to be siloed. And so it takes a lot more effort to break out of your domains and interact with people from other disciplines.

But there are funding opportunities that are available that are specifically for interdisciplinary or what some sometimes call convergent research, which is basically where if you think of interdisciplinary research or multidisciplinary research being sort of like a fruit salad where you cut up all the disciplines and you put them in together, convergence research is where you blend it up into a big smoothie where you can't even really tell where the lines cross.

I heard this is not my idea. I got this from someone else's talk. But and so there are opportunities in academia to do this. I think it can be harder because we're all busy and it takes time and effort to communicate across disciplines. We have sometimes the same words mean different things, and so overcoming those dealing with communication and disciplinary issues can be a real challenge.

But I think it's worth it. I think we have a great opportunity for students to work on interdisciplinary teams and in something called an enterprise. So it's basically like a small company that student run and student led, and companies sometimes come in and propose projects that students can work on. And so we have one that's on rail transportation, I believe, and in my department we've got one on consumer product manufacturing.

But it's not just chemical engineers. They're students from lots of different disciplines. And so there's sort of topic and interest based as opposed to domain based. And so students get that experience as well, working on teams of people from different disciplines. It's a great opportunity.

Meg Riker: Did you ever want to change or turn completely to a different professional field because you have all these broad interests is partially why I'm asking. And then I'm also asking because I myself have been occasionally like, Oh my gosh, should I be doing something different with my life? So I just wondered what your perspective on that kind of topic was.

Rebecca Ong: Definitely. Absolutely So. And I think it's true maybe more for women than for for men, because we're taught that if we we fail, that we're not good at it. Right. And maybe we should do something else. And so it's really easy when we hit something and are like, I just total that totally did not work. Maybe I'm not good at it.

Maybe I should go do something that is easier. So when I was an undergrad, I worked in the costume department here at Michigan Tech and I did cosplay costumes for plays. And I also had an award for art. And so when I hit Snags in graduate school, I'd be like, I'm just going to quit and I'm going to go into costume design and I never did and I stuck it out.

But, but you hit those times and you're like, Oh my gosh, It's like this fantasy. Like I could go and do this completely different thing that's in a completely different area and have a lot of fun doing it. When I finished my Ph.D., my husband had already had a position at Michigan State, so first, so I wasn't able to get a faculty position.

So we stayed and I work continue to work for the GLBRC but I started doing graphic design as well, scientific graphics. And so there are times when I'm like, Well, I can't do the faculty thing or I can't get in industry. Then now I'll make I'll do scientific graphics because I enjoy that and it's a lot of fun and I don't get to do as much of it now, but it's still something that I love.

Meg Riker: What do you wish everyone or just other people in academia understood about your job and the benefits that it might have, but also the difficulties that you encounter?

Rebecca Ong: Oh, two big things as a faculty. One, you don't get summers off, and two, even though you're not paid for them, often unless you get grants to pay for them and you're still working less. I don't work quite as much in the summer, but I still work a lot. And then to teaching is a small part of my job, so I love teaching.

It's why I'm here. But for my job, I'm teaching. Maybe 10 to 25% of my time is spent on teaching and so the rest of it is managing my lab. It's kind of like running a small business, trying to get funding for my students, trying to manage all the projects that we have going on, being in meetings, writing reports, editing papers, serving on committees at the university and in institutions around the world.

In my professional society. So there's just a lot of components that are my job that are not teaching. I want them to know that teaching is important to me and I still care about them. Even though I'm very busy with these other things. I tell my students I have a I have an instant messaging system set up for my classes because I want them to be able to communicate with me quickly and not get buried in my email inbox.

I tell them I'm like, The reason why I have this is I spend about an hour and a half to 3 hours of my life every day answering just answering emails. So I don't want your stuff to get buried in there because I don't check my emails on the weekend for a few barriers on my time.

Meg Riker: What advice would you give to your younger self? Relax, I like that one. I could use that advice.

Rebecca Ong: Yeah, to attract people. People are okay for the most part. And don't be afraid of failing like you're not a fit. Just because you fail doesn't make you a failure. And we learn from failure. So take your failure, turn it around, learn something from it and bounce back. Yeah, I think we're trained from a young age, especially as women that, Oh, you're you get good grades.

Oh, you're good at math and science. And if you don't good grades suddenly, oh, that means you're not good at these things, which is not valid. And I think it's a different message than what we sometimes tell boys.

Meg Riker: Notice how hard or easy do you think it is to balance your work in your field and with your personal life?

Rebecca Ong: It takes some tension. So I try not to work at all on Sundays. So that's kind of my day that sometimes I have to like. I try and be available for students if they've got questions on homework because their stuff's due on Monday. So sometimes I'll answer some things for them, but I try not to like plan time when I'm working on Sundays if I can do it.

But yeah, just being intentional about when I work and when I don't work. So when I go home after I'm done working, I usually don't work. I try and focus on my family and then that me. But that means in the evening that I need to do a little bit of work after my my daughter goes to bed, for example.

So it's just, I think, setting times and setting boundaries and sticking to them. You also have to make sacrifices. So there there are times when I don't go to things, I don't go to conferences, I don't go to events because my husband's also an academic. So we have to balance the things that we do because someone has to be here to take care of our child.

Meg Riker: Could you tell us about a time you've struggled either personally or professionally, if you feel comfortable doing so, or on the flip side, have you run into any unforeseen obstacles on your path and how did you overcome that?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah, so I think there there was a there was a time when I was in graduate school that I was working on this project and the whole project was predicated on an assumption of what the plant characteristics were, right? So we had to do a whole experimental design that was based on these plants, had those characteristics versus these plants that had slightly different characteristics.

And so I'd done all the work, I'd gotten everything done and assessed. And at the end of the day, when we retested, they were based on a mathematical model based on what something called an R data. And so then our data is entirely based on you scan the sample with light, you read the structure that it gives back to you, and using that, you put it to a model that predicts what the composition should be when my collaborators actually went back and tested it using chemistry in the lab, they found that it was completely wrong that our entire experimental design was flawed, that it was completely unusable.

So I went and did all of this work, and at the end of the day, it was garbage because we couldn't get anything out of it. And so that was hard and that was stressful and it wasn't even anything that I did, right. So it was entirely based on just flaws in assumptions and flaws in the model, and it ended up not working.

And so coming back and realizing that sometimes we're going to do things and we're going to try things that don't work and sometimes it's our fault and we planned things wrong or we did experiment wrong. Sometimes we have no idea why things didn't work out the way they did. Sometimes those can lead to new research areas, and sometimes it's just a project that dies and it's abandoned.

And that happens quite a bit actually, in research. So sometimes you have this project and you think it will work and then it doesn't and you can never figure out why, and it just ends up as a dead project and that's okay. And acknowledging that and accepting that moving on to the next thing.

Meg Riker: What advice do you have for younger students or grad students how to manage this frustration or kind of put it away a little bit and not try to be like, oh my gosh, how do I figure out this problem when it might not be a solvable problem?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah, I think when most of you are working with a mentor. So talk to them, get their perspective, find it, see if they have ideas for why it's not working, and if it's something that's fixable. Because you're not you're not working, you're not working in isolation. None of us have to do that. And so sometimes I'll go and talk to colleagues who are in a related area or in a completely different area.

But I know they work in this. They work on this piece of equipment or they do something similar that I think might have relevance. And I can talk to them and say, Hey, this isn't working. Do you have any ideas for why or thinks we might be able to try instead? So talking to people can be very helpful.

Sometimes I'll scour the internet for ideas like I do a lot of Google searches for people who have done similar things. And these aren't not necessarily things that are published in papers at least. Sometimes it's in forums online where people are like, I'm trying this thing and it didn't work and people will come back with their ideas. And so I get a lot of perspective from that as well.

But I think at the end of the day, you just coming back to what I said before, that if it fails, it's not because you fail necessarily doesn't make you a failure. It's a failure that you go through and you learn from it what you can, and then you try something new. And I think stepping away just just going and doing something else, we all should have things that we do outside of work.

That's true of academia as well. So I like music and I like art and I like crafts and crocheting. And so I'll go home and maybe I'll play my ukulele for a little while and learning how to do that, or I'll work on some sewing because I enjoy that as well. Or I'll play a board game with my husband and all that to him for a little while.

And having things that you can do outside of work can be really helpful.

Michelle Chung: And also for those of you listening in Becky shared some awesome pictures of her costuming, some of her crafts like her singing and quilting, and a scientific graphic she's done for GLBRC, and I have to say, they're all pretty spectacular. You can take a look at all those pictures in the show notes on her website, but back to Becky.

I have another question for you. You talked about sharing childcare responsibilities with your husband. I know for many of the women we've talked to on this show, having a kid can be super hard while being an academic. What was that journey like for you?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah, so we wanted to have kids for a while. It took us a while to have her. I ended up having her, so my husband got his job Before I did. We moved here for his job and I was working remotely part time with the job, working on writing and projects and managing things. But I wasn't working as much.

We were able to get part time childcare for her while I was working quarter time with the job overseas. I wasn't balancing trying to find childcare while also having a full time position that would have been crazy hard. I can't imagine what we would have done otherwise because it's really hard to get into childcare here where we live.

I got my full time position when she was about how old was she? Eight months old. So I started my job and at that point still didn't have full time childcare. And so we were lucky enough to be able to call grandparents to come and help watch her for a month until she could get into full time childcare.

So and it took her out of conference once when she was five months old and paid for my mom to come and help me because there's no childcare at a conference, usually at least this one. And so she came and would watch her while I was attending meetings and getting my talks, and then I'd have to come back and take care of her periodically during the day as well.

So it was not it's not easy. It's it's really not easy to be able to balance those things. And thankfully, having parents who were able to help. But if I hadn't had had that, I don't know what I would have done. I might have had to I might not have been able to go to the conference or do a lot of things I want to do. So.

Meg Riker: So what, if any, do you see as continuing obstacles for women in your field?

Rebecca Ong: Mm hmm. Well, chemical engineering is actually really great. We're pretty close to 54, 50 women and men. And that was true when I was a student as well. And I don't know if that just has to do with my university. Where I met, we had a lot we had quite a few women faculty who taught our classes. And so you could see that there were women who were working chemical engineering women at a school.

And I, I think there's been a focus in industry as well to try and maintain that gender parity to and certainly not true in other fields of engineering. And so I think that fields where it comes across as more of a masculine domain like mechanical engineering or electrical, there's still a real struggle to try and get women to be involved.

But I do think that starting at a younger age, trying to help women understand when they're girls, I guess, understands that anyone can do engineering when they're in elementary school is really important. So we start to internalize our beliefs about our abilities as young as 4 to 6 years old, right? So if you're told from a young age that, oh, you're just not you don't do well at math, so maybe you're not as good at it, maybe you should focus on these other things, then you tend to internalize that, and it's really hard to lose that as you get older.

And so if we're making an effort to show kids that anyone can be an engineer or anyone can be can do math and do science, then I think that we might see a shift in how many women go into these different domains. A few years ago I was collaborator with a colleague here at Michigan Tech to run some engineering education programs for pre-K teachers, teachers who are in daycares and kindergarten classrooms and teaching them how to teach engineering curriculum.

Because a lot of times the big barrier is that these teachers have no training in engineering. They don't even know what engineering is. And so trying to convince them that, look, you do engineering every single day. There's a engineering design cycle that is like, come up with ideas, design your idea, test the idea. If it doesn't work, go back to that, go back to the beginning and revise troubleshooting and try it again.

That's called engineering design cycle. And in microbiology they call it design, test, build, learn. But that's not a new thing for microbiology. It's the engineering design cycle that we use all the time. And teaching a middle school teacher, Look, you do this when you do your curriculum, you design, you test it, you build it, you learn from it, and you start all over.

Or when you maybe work on a recipe and you want to improve your your cooking skills, you can do the same thing. And so giving them small projects that they can do with the kids and and that we work through with them and train them on how to do it. And they're like, Oh, I can totally do this.

It was so exciting to see how excited they were at the end of these these workshops to go into their classrooms and actually help their students learn how to be engineers. It was really great. So I talked about early early childhood start that that helps get students, I think, into engineering and STEM in general. But I think also ensuring that you've got diversity among your faculty is important so that people, when they come in, they're like they can see themselves in, in the work that's in this major.

They can they can possibly doing this as a career because they see people like them there. And that's not easy to do, right? But I think it has requires you to be intentional. So when I first was applying for faculty positions, a place the one place, one of the places I interviewed, there was one woman faculty in the chemical engineering Department, which was a shock to me.

And like everywhere I'd been before them, there were much more than that. So I think they were putting an effort into hiring women and more women faculty to try and improve that that ratio. But I think being intentional about hiring people to show the diversity of people who can succeed because we all can succeed like everyone can succeed, I think I think there's always a risk of it being a token, right, that you're just doing it because it's culturally important right now or because the university is like, we need we need this to happen.

Instead of actually being for the right reasons. What do you do about that? I don't know. I think a lot of it's culture shift, right? And people being willing to communicate and have dialog about things and understanding and training, I think as well, like teaching people like, you know, this thing that you you might say it's actually not helpful, it's actually harmful to people.

It makes them feel like they're not welcome. And you don't always think about it. Sometimes you're just saying something and you don't realize how it comes across someone else. And so trainings, I think, can help with that and helping people understand things that they might do that they don't realize they do that are harmful and causing and perpetuating the discrimination in the workplace.

Because we all have biases, right? We all have have biases we don't even realize that we might have. And they come out and they affect the way we treat people and without even realizing it. And so understanding that we have those can cause us to change our behavior.

Meg Riker: Do you still see discrimination in academia?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah, there's definitely still discrimination in academia, and it's not always blatant, right? Sometimes it's just small things that build up ways people interact with you differently than you see them interact with someone else who's out of the same career stage or little things people say or, you know, it's not necessarily something like really, really big where where people are actually trying to run you physically out of the university or out of your career.

I wish we lived in a world where these things don't happen, but acknowledging that you belong here, that we're happy to have you here, that you are, you bring value to where you are just by being you. And you don't have to prove yourself to anyone right? I think you don't want to put the onus on people to make the changes.

Right? So it's hard because you want to ask the person like, what can I do to make things better? But at the same time, you don't want to put all that burden on the person who's going through this, Right? So so making efforts yourself to see what are ways that I can help be an ally and support and call things out when I see them happening and helping people feel that they're welcome and they belong in the spaces where they are right?

Meg Riker: Do you see this changing in the future. These kinds of problems?

Rebecca Ong: I think so. I think I think people are becoming more aware of what other people are experiencing and that there's a desire to change and a lot of people in academia, and that's encouraging. I think being willing to absorb things from another person's perspective or walk in someone else's shoes for a little while and realizing that, oh, I had no idea you experienced things like that and listening, really listening and not just dismissing someone's experiences.

I do see some change happening.

Meg Riker: What do you think drives this awareness? Is it institutional level actions or is it a social kind of thing, or is it the fact that we see more women coming through despite the obstacles? What do you think?

Rebecca Ong: That's a good question. I think there's a slight culture shift that might be happening and it's not necessarily institution driven. I think it's usually started from with in academia. I think it's usually started from among the faculty, people who have experienced this and think that it's important to make a change. I don't see it coming as the administration endorses it and approves of it, but I don't see it being like a top down, and I don't think it's as effective when it is.

I think it's better when it's coming from grassroots, where it's coming from, from the people who are experiencing it. I won't discount institutional support being poor, and I think it is. Yeah, like if you're institution is not supportive of you, then it's going to be miserable to try and do anything right. Yeah, but I think that institutions driving it may not be the best, but I think you're institution definitely needs to be supportive or you're going to it's going to be a nightmare to try and get anything done.

Meg Riker: But how do you think the wage gap between women and men, especially academia, could or should be addressed?

Rebecca Ong: I don't know if there is as much of a wage gap in academia as people think there is. I think that oftentimes the data is confounded because it is drawing across all disciplines simultaneously. So I think that when you factor in to that, the that some disciplines have lower salaries than others, that I think that would that wage gap would shrink quite a bit.

I will say that when I was hired, I came in in a situation where I was not planned work. So I was a dual hire for my university. And so when I started, there wasn't a lot of funding available for me. And so I actually did come in at a lower pay than my male colleague who started the same time.

And I didn't realize it until my current chair. One of the first things he did was institute an equity equity raise for me and apply for that. And so then that bucks me back up to where I was comparable level. So I think that there are things institutions can do to rectify past situations where maybe there was more of a pay gap between men and women.

I don't think that's as much of a concern for faculty starting in general and institutions now. Yeah, my understanding is also women are less likely to advocate for promotions for themselves, right? And so when I hear this from our external advisory board members and the women who are on our board of alumni, they come in and they're like, Yeah, I had no idea that I could talk to my manager and say, I'm interested in promotion.

And then my manager came back and said, I had no idea. Why don't we focus on some career development to get you ready for that? And so being an advocate for yourself, we just think, Oh, it's just going to happen. They're going to see the good work I'm doing and it'll just happen organically. And that often isn't the case.

You have to be you have to do a little bit of self-promotion sometimes.

Meg Riker: But how can we address inequality issues for mothers to raise and people with disability, even though they all fall into like separate categories with different concerns? I was wondering what your perspective was on how we could help these people succeed in STEM.

Rebecca Ong: I mean, there are different levels at which this would need to be addressed. Right. And I think the thing about parents and disability is you don't always it's sometimes invisible. You can't always tell like people aren't necessarily bringing their kids with them to campus. Keep some a lot of disabilities are invisible. You can't really see people who are not neurotypical, people who maybe have not immune disorder, and it just makes them really tired.

Right. And so I think being accommodate willing to accommodate people for different whatever position they're in. And so our university has students can request accommodations and that's great. And a lot of students do this but I where function in my classrooms is I try to give students as much benefit of the doubt as possible. And so when students come in and they request accommodations for me, like maybe I need a little bit more time and an assignment, usually I'll just give it no questions asked.

Definitely for the first time they ask and usually doesn't really cost me anything. So I'm not grading on assignment the day it's due. And so a day or two late is usually not a not a huge deal. I have a blurb in my syllabus for my courses that says that basically for people who are parents that if there's a time when schools are canceled or something like that, that you're welcome to bring your kids with you to my class.

I asked them. I'm like, Please sit near the door. That way. If for some reason you need to go out with your kid, that way you can you can dash out the door really quickly. And I ask the students to leave spots open for them if that's the case. But just providing helping people understand that you're welcome here, that you're welcome to ask for help if you need it, and that I'm open to to working with you to ensure that your successful program.

It is hard to balance, right, Because you're also like, I don't want to be super lenient so that students like like we have slack people slack off. So it's it's it's a struggle to maintain that balance, to be flexible. I'm willing to accommodate people and also like not skimp on the rigor that we want you to be prepared for your futures too.

So it's not an easy thing to do.

Michelle Chung: You mentioned earlier on that we should put the burden of fixing problems on the people that are experiencing the harm. I know you're part of this organization that tries to address this problem, A3b, Can you talk a little bit about that?

Rebecca Ong: Yeah. So so I'm on something called the Advocates and Allies Advisory Board a3b or three As and a B. Our university got an advanced grant and I wasn’t a part of that. This happened way before I came here. So by some really excellent people at my university to try and improve equity and campus culture here because there were quite a few issues in places.

So they got the funding and it was really focused on developing. There are a lot of things that they're focused on doing. One of the things is developing these advisory committees, one of whom is a team called the Advocates, and this is largely it's a team of male faculty staff who are striving to enact change at the university.

And so they're made to submit applications and the A3B goes through them and decides who gets admitted to that team. And their job is really to be the ones initiating training and engagement and workshops and seminars and engaging with the campus community to try and make changes. The A3 B, we're here to make sure that they're talking about stuff that we think they should be talking about, like they're raising issues that we think are important, that they're focusing on things that we think are going to make a difference.

And so we're not the ones initiating those efforts. We're just helping guide them as they're doing the work. So the change is coming from from men, which can help men see that it's important and get more involved. So I think that's extremely, extremely good.

Michelle Chung: I’m curious–what what’s something that’s come out of that?

Rebecca Ong: That's a really great question. We haven't been around for long. I think it's this is the third year it's been in place, so we've done quite a few workshops on campus. There's a workshop every semester where people from the campus community come and we discuss issues. There's a journal club that meets. It's hard to know if there's change because it's only been going on for such a short time.

So I do sense a shift in campus culture, and I think part of it is through these activities and through the workshops that have been going on a lot of people have attended them and I think it's been helpful. It's not just the women and minorities who are showing up to these men too and white men. So it's encouraging also to go in the room and see these men who are there and to care about about seeing change and supporting all of our colleagues on the university.

[MUSIC]

Meg Riker: There's so many things I loved about this episode. First and foremost in my brain as a student, I thought her opinions on how to treat her students were really novel, but also like, great. Like, I've never had that here. So, you know, we in engineering, but I thought they were really cool and really student centered. Part of your role as a professor is to be compassionate towards your students, and I feel like that's sometimes missed in the engineering discipline.

So I really love that. But more for me was her distinction between different parts of her career and then the role institutional support does and played throughout her. I definitely heard different parts of her life and career that were impacted by her institution and supporting her or the lack of support. So like, the first thing I think of was like when she was talking about how she got an equity raise when her new chair came in, which I hadn't really heard of before.

So like, I was like, That's a really positive thing. You're doing something for equity for women from an institutional perspective. But then she goes on to talk about childcare and how she would really love some form of institutional support, whether that be her university or the government or something for paying child care workers more. So I think those kind of jumped out to me, even though she wasn't speaking directly about institutional support and then she also talked about the committee of men who work to support women colleagues at her university, which I had never heard of before.

My main wondering pondering about this is like, what is the true effectiveness of such a committee? Conceptually, it seems like a positive idea, but it could be swayed if it led, if it was led by the wrong people. So of course, this is also the issue with anything that's comes from an institutional perspective. I'm just wondering what your thoughts on all that is. It's a lot is a lot.

Michelle Chung: I know right off the bat I had thoughts about the last thing and yeah, the the committee of Men is such a innovative idea like it really it could have such great positive impact. But I had thoughts where it seems like an opportunity for performative action. But like she said early on, this work is slow, it's hard to assess and maybe it is part of building that culture shift we need to see.

Meg Riker: But the other thing about the institutional support, so like we see that some institutional support does exist when the right people are in place for these things, such as like equity raises. But we also see like and we've heard this so often, childcare is such a concern for so many women and it's something that any institution could do something about and solve a outstanding issue, one that comes up more and more.

Yeah, So yeah, I loved her perspective on this.

Michelle Chung: And that's our show for today.

Meg Riker: Thank you to Dr. Rebecca Ong, Associate Professor of Chemical Engineering at Michigan Technological University.

Michelle Chung: And thank you for everyone listening in Please Subscribe Rate review and share this podcast with a friend.

Meg Riker: You can find the Wisconsin Energy Institute at energy.wisc.edu and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center at glbrc.org

Michelle Chung: This episode was produced by Michelle Chung and Meg Riker. We'll see you next time on Propelling Women in Power.

What is your superpower?

Rebecca Ong: I'm a I'm a systems person, so I look at things from a systems perspective, seeing multiples perspective and seeing how all the pieces fit together- that’s something. To be able to look at a problem with all these different pieces and being able to do something new and useful.