Episode 1: Fusing STEM Communities with Stephanie Diem

If you take an atom that’s just floating through space, spin it around at a really high temperature, and – pow! – smash it together with another atom to make a big nucleus, you end up with a bigger, more powerful, and stronger atom. In the meantime, there's a big release of energy that we can theoretically capture and turn into electricity. The problem is, it's really hard to keep the reactions going while capturing the energy that this powerful punch produces.

This is the essence of fusion power, the elusive carbon-neutral energy source that researchers have been trying to harness for almost a century. Today's guest, Stephanie Diem, assistant professor of engineering physics, is at the forefront of this research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. While she uncovers the clues to turning this technology into a viable supply for society’s energy needs, she’s working on ways people like her - women in the nuclear energy research – can sustain themselves, and grow to constitute more than just the current 10% of the field.

Listen right now on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Youtube, or anywhere podcasts are found. Or you can listen below!

Credits

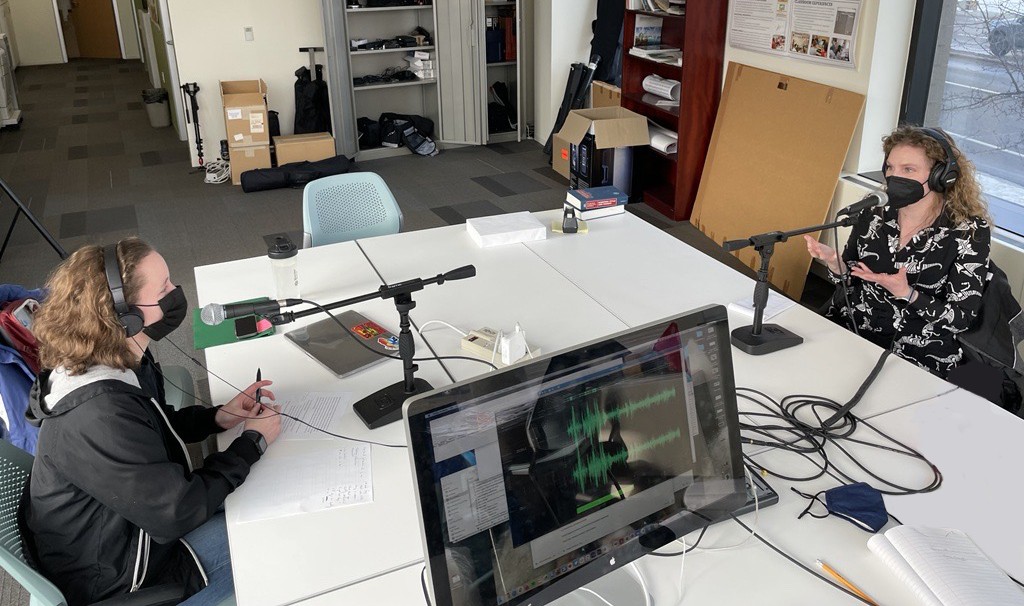

Michelle Chung | Host

Michelle Chung | Host

Communications Specialist

Mary Riker | Host

Science Writer Intern

Editors: Mary Riker, Mark E. Griffin, Wisconsin Energy Institute Communications Specialist

Producers: Michelle Chung, Mark E. Griffin, and Mary Riker

Music written and performed by Mark E. Griffin

Transcript

Mary Riker: Hey Michelle, do you know what fusion energy is?

Michelle Chung: Yeah, so like you take an atom that's just floating through space, maybe looking for a molecule to join up with or just doing its own thing. Then you spin it around at a really high temperature and -POW! Smash it together with another atom to make a big nucleus. It's bigger, more powerful and stronger, just because it got combined with another one like it.

Mary Riker: Yeah, and when that happens, there's a big release of energy from the leftovers that we can capture and turn into electricity. Except the trick is we don't really know how to do it well yet in a way that the crazy reactions necessary to do it are sustained. So right now it's "smash some atoms, fusion reaction, and POW!, gone". Start over, smash some atoms, fusion reaction, POW, gone, POW, gone.

Michelle Chung: POW, gone, POW, gone.

[MUSIC]

Michelle Chung: Welcome to Propelling Women In Power, a podcast about the careers of women in energy at the Wisconsin Energy Institute on the UW-Madison campus and our sister institution, the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center.

Mary Riker: I am Meg Riker, and I am a junior undergraduate student studying civil engineering. I am a science writer intern with a passion for meeting people from different scientific disciplines and sharing their stories.

Michelle Chung: And I'm Michelle Chung, a senior undergraduate student studying Biology and Environmental Studies. I love finding fun ways to highlight the research and people here at WEI and GLBRC.

Mary Riker: Here, we talk about women scientists and engineers' career paths, the obstacles they have faced, and most importantly, their advice for young women scientists and engineers. It is our goal to highlight their individual experiences, mentors, and work-life balance while seeking advice for young women in science and asking the question, "who and what facilitated your success?"

So today, we check in with Stephanie Diem, an assistant professor in the Engineering Physics Department, who is at the forefront of this research on the UW-Madison campus. And at the same time, she's working on making these reactions work in a continuous way to sustain society's needs for energy. She's also working on ways people like her, women in the nuclear energy field, can sustain themselves and grow to constitute more than just the current 10% of the field. So let's take it away with Steffi.

Stephanie Diem: My name is Steffi Diem, I'm an assistant professor in the Department of Engineering Physics. I design microwave systems to heat gas up to millions of degrees, ten times hotter than the sun so we can reach fusion conditions.

Mary Riker: That's so cool. So you're you're literally like a nuclear scientist.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah, so my undergrad degree is from UW-Madison in nuclear engineering. Then for my PhD, I went and switched over to physics. So I have that combination of the applied side of physics and the deep fundamental understanding of physics.

Mary Riker: So could you tell me a little bit about how you decided to get into nuclear engineering? .

Stephanie Diem: Sure. Great question. Okay. So in high school, I really liked a lot of things. I was a curious person. I liked art. I liked science. I liked math. And I really couldn't decide. I was leaning more towards art actually the end of high school because I was really unsure of my ability in science because it took me, I found I spent a lot of time on the homework. And I thought that was unusual and reflected. I wasn't good at it. But my parents were like, you know, what? Why don't you go for engineering? And I had a teacher say that too, they're like, "You're actually really good at it." And engineers can get jobs. I mean, parents are very practical, right? Yeah.

So I went to UW-Madison, I didn't know what an engineer did. I didn't even know what kind of engineering I like. So I talked to a lot of different students here on campus during the weekend where you all kind of register for classes, right? And so I met nuclear engineers, and they said, we do a lot of math, we do a lot of physics. I'm like, "Oh, that's amazing." And we apply it to clean energy. So I really liked that understanding of physics, and then at the heart of what I like to do is help the world right, solve problems that are important to humanity. So that combination was amazing to me. So I'm like, "Okay, great. I still don't know what an engineer does. I should probably figure this out before I major in it."

So second day on campus, I started freaking out because I had no way to pay for school. So I went to my department chair and I said, "Who is hiring student hourlies?" I kind of started going down the list. And the first person that happened to be in their office give me a tour and that's the day I learned about fusion energy research. And it was amazing to me because he explained it as kind of what we're trying to do with fusion energy is heat up gas to millions of degrees and then it's so hot, the nuclei can fuse together and release a lot of energy. Because the fuel so hot, you have to be creative about confining the fuel for fusion, so we make magnetic bottles. He described the way you can find the fuel for fusion with these magnetic bottles, kind of like confining jelly with rubber band. And, to me, that was so fascinating because it's a really complex problem. And we're actually really good at confining the fuel for fusion with these magnetic bottles. So it was kind of hooked to that, that day when I heard about it.

Mary Riker: So I want to jump back to something you said right at the beginning, you said you were unsure of your ability to do these kinds of science and math problems, because they took you a long time.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah.

Mary Riker: I definitely relate to that. Because there are certain classes I've taken, I've just doing the homework, you can do it, but it takes forever. And I know I've talked to other women in engineering, and they see that kind of as a sign that they aren't they aren't doing well enough in a class. What would you say to them? Or is there a way that you kind of got around that kind of challenge when you were in high school? And even in college? I'm sure.

Stephanie Diem: That's a great question. I think it was coming to the realization that everyone takes a long time to do these problems, but no one's talking about it. If they're talking about how long it took them to do a problem, they may be not very truthful with how much effort they're actually putting into it. Right? The other thing is, what we're trying to do, as engineers and scientists, is amazing and complex and life changing. And that's hard. And there's huge payoffs. And it's fascinating. So of course, it's going to take some time to understand that. And you know, not all subjects come naturally to me, too. So some I find, you know, different aspect areas, just because it's not something I'm used to, I have to put a little bit more time in to conceptualize that or understand the math behind it. And that's totally okay. Because you're learning something new to you too.

Mary Riker: You did research while you were an undergrad here. How did that experience impact your trajectory? Or maybe your future to go? Because I know you went to Princeton for your PhD.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah. So that's a great question. It really helps you understand what you like to do and what you don't like to do. So I learned that I liked to, you know, work with electronics. And that's great. Maybe not build high power circuits to like to run power system, but more for the diagnostic scale. So that was good to understand. I found different aspects of fusion energy that I really, really liked. And that kind of gave me the tools into how I'm looking into a graduate program and what I want out of it, and kind of what projects I might want.

Mary Riker: Were you the only woman in your research group at that time. Were there other women that were there for you to identify with or associate with?

Stephanie Diem: So when I was an undergrad, at some times, I was the only one. And other times I was like, maybe there was another one or two? Yeah.

Mary Riker: How did that translate or change your experience?

Stephanie Diem: Oh, great question. I will say also, in my degree program, I was the only one oftentimes but I actually didn't notice it here, I think because the people I had been working with at the time were so inclusive, and they really empowered me and my professors, and I'm saying this from my personal experience, I didn't notice that at the time.

Mary Riker: So Michelle, let's cut in for a minute. Do you have a reaction to Steffi's comments?

Michelle Chung: I thought it was really interesting how she said, "Yeah, there weren't a lot of other women in her undergraduate program." But what was different was that the people that were in that space empowered her, and they were inclusive. So that's an interesting case where there weren't people that look like her around her. But the people that were around her were inclusive. Spaces, spaces that don't have like the identities of people to make them diverse, can still be inclusive and empowering.

Mary Riker: I think Madison does a good job actually, without for most people, of including people, even if there aren't others that specifically look like them in their research groups.

Michelle Chung: Yeah. And people are always like, "Well, there's, there's not people to make these programs diverse." But in order to do that, you have to first be inclusive and including even if like there aren't people.

Mary Riker: Right, so one has to be the first person and you have to make them feel welcome enough to...

Michelle Chung: Right, yeah.

Mary Riker: ...then bring in others or tell others that you've had this good experience?

Michelle Chung: Yeah, like it starts somewhere.

Mary Riker: Let's hear about the next phase of Steffi's career.

Stephanie Diem: When I went to graduate school, I was working at a national lab setting with the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory. And so when you have this mix of you know, some graduate students and I was one of like, only a couple in our graduate program. It did influence, actually, I think my thesis a lot. Dr. Cynthia Phillips, she was one of my thesis advisors, and she was brilliant. She was amazing. She was just someone I wanted to be and I could see myself in her and so she really taught the waves class. So how matter and waves move inside of a plasma, and I think that's part of the reason why I specialize in waves plasma waves really.

Mary Riker: So having a mentor that looked like you and maybe sounded like you really kind of influenced your decision to go into this field too in the first place?

Stephanie Diem: Well, for definitely my specialty.

Mary Riker: Okay. Yeah.

Stephanie Diem: Because that was the first time I had seen a woman working in our field.

Mary Riker: Okay.

Stephanie Diem: In graduate school. Yeah.

Mary Riker: That's really cool.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah. And I don't think I noticed that at the time. But like looking back, I can see how much of an influence it made.

Mary Riker: One of the things that I had when I went to college, I was part of a group specifically for women in science and engineering, and I lived with them. It's called the WISE program here at UW Madison. Do you think having those kinds of communities helps women succeed? Because in my case, it definitely did. Do you think having had that maybe, I don't know if like a different version of it in grad school would have helped you or just make you feel better, or have those more shared experiences?

Stephanie Diem: I think it definitely would have helped. So especially like looking on after, when I went and got a job after grad school, I was the only one in my division. That is very lonely, and you have no support network, no shared experiences, and I didn't really thrive. And I really wish I would have had that, I think it would have made a huge impact. I will say that having lived through that experience, I don't want anyone to be in that position again. So I love programs like the WISE program. The other program that we have on campus that just started, one of the graduate students in our department, Carolyn Shaffer, started it, she actually got a grant from the American Physical Society, from the committee for women in physics. So she started across, this is across campus, it's the Solace Group, it's, it's Spanish for the sun, because it's a group for gender minorities and women and plasma physics. And this is across campus. So it's building these networks of people that work in your field. And especially in our field, when there are very few women or gender minorities. I think this is very important. And so it's just been so happy to see that because I wish I would have had that and seeing them interact and and having great experiences, it just makes me so happy.

Michelle Chung: Let's pause for a second. So Meg, what exactly is WISE?

Mary Riker: So WISE is is the Woman In Science and Engineering program here at UW-Madison, for women who are interested in going into those fields, who can, they all live together in Waters Hall, and they get certain discussion sections that are all women, and they have activities for women in science to just hang out and get to know each other. And it's a good way to build community as a freshman here. When I took it, it was run by Sue Babcock, who was one of the first women faculty in the Material and Science Engineering program here at Madison. And having a like a role model like her was really influential to like how I saw issues for women in science. And for a long time, that's why I continue to do stuff for women in science and why it's important to me too, because hearing about her experiences, I wouldn't want to have those and I wouldn't want anybody else to have those. Or to fall back on that. She also brought in women from other disciplines on campus in science and engineering to speak about their experiences. She brought in people from industry to talk about their, their experiences too and what it's like in the real world, which was also really eye opening, I thought. If you're not, I think, if you're not diligent about it, or you don't keep talking about it, you could lapse back to something worse. And that's kind of a little bit scary.

Michelle Chung: So it sounds like maybe there was a little element of fear of like what we could go back to,

Mary Riker: But it was also really compassionate. And she was really well spoken about it. She had this energy. That was really inspiring because obviously since she was a teaching faculty, she was well respected within her department involved in science outreach. And she led this program. I don't know how the woman ever slept, but she just was really inspirational. So it's just a really good program to get some exposure to both the academic and the like real life side of being a woman in science.

Michelle Chung: Yeah, that sounds great. Like there was active community building like past like the levels of undergrad to like she invited other women from like industry and others.

Mary Riker: Mhm, and I know a lot of people made their friend groups from that and continued. Like, they go on to live with those people, or they've gone on, like me, to still see them today.

So let's get back to our interview where Steffi and I talk about that sense of belonging and what it can do.

[MUSIC]

Mary Riker: Just like getting to talk to other women in science, and even if they aren't in my field, it just builds you up in a very different way than like doing well in a class or something like that does.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah, I think it also helps build resilience. Me too.

Mary Riker: I agree, that teaches you that the people you're working with are struggling with the same things. And if they're struggling and you're struggling, it's okay.

Stephanie Diem: And it's one of those things I just really didn't notice, or I didn't appreciate how much of a difference it made until I had nothing. And then you go to a supportive network, and you're like, "Oh, I, this is what I was looking for all along."

Mary Riker: So can I ask you about what it's like to be the only woman in a program and how that makes you feel? Or what kind of impacts that might have?

Stephanie Diem: Yeah, great question. So, so, for me, especially in, this is looking back when I was the only woman in a program, it's the "I had a lot of doubt. And I couldn't talk to anyone where it was coming from, or I was unsure about my abilities, or even someone to acknowledge the microaggressions that I was experiencing," because they can see it, too. And they've experienced it. And I think there's a different level of understanding where you can say, "Hey, this person came up to me and told me, 'What are you doing wearing that? You don't even look like you belong here.'" And they're like, you know, people have said that to me, and it's horrible. And I'm sorry. And then you can just, you know, build that resilience to be like "That guy's a super jerk here."

Mary Riker: But that's probably very tough to go through on your own.

Stephanie Diem: Yep.

Mary Riker: But what do you think is changing? Do you think it's changing now?

Stephanie Diem: I think things are changing, because people are being a bit more, people are being more vocal. So I am more vocal on social media about this stuff. Which means not only do I have my network backing me up, but to be honest, I have men in my field contacting me and being like, "Hey, let me know when this is happening at this institution or that institution. And I will help you out." I think it's the transition from me feeling like I am fighting a system by myself, to me actually relying on other people to help me and to do some of the work that I was doing all by myself.

Mary Riker: So what's it like to have men come to you and say, "How can I help with those?"

Stephanie Diem: It's really empowering, because they are, they're offering their help, and they're believing me. And they want to make changes. Yeah, I mean, not so, so I don't mean it to see like, "Everything's fine and a magical right now", right? No, it's gonna take time. But there's more people helping. And that's very reassuring to me. So at our professional society, we have allies training, where it's kind of like bystander intervention training, what to do, and to step in to stop microaggressions, to stop harm and things like that. And I think when you go through, like, I went through a cohort of people who have done that training, so we have our own network. And so next year, we train more allies. And so you build it, and then you get people higher up at institutions. And that kind of helps to if you can get involved in things like that. That kind of helps you grow your network faster.

Mary Riker: Have you? Do you continue to experience imposter syndrome? Do you? Could you maybe highlight a point where you feel like it was the worst or it's gotten better? For you?

Stephanie Diem: Right off the bat, I have trouble with the word imposter syndrome, because it's putting it on the minoritized population, like it's a problem with you, when you're trying to navigate in a system that wasn't designed to include you. Right, so I'm just gonna put that out there.

Mary Riker: No, that's totally 100% valid. Yeah, really good.

Stephanie Diem: Oh, what I do do to acknowledge that I am here for a reason and I deserve to be here is I am continuously updating my resume, or my CV, because those are objective things that I have done that no one can take away from me, right. And so reminding yourself of what you've done to get this far, I think helps a lot for me is reframing it.

[MUSIC]

Mary Riker: Let's pause again to talk about a phrase that comes up quite often during this podcast. What do you think, Michelle, about her definition of imposter syndrome or why we shouldn't use that word?

Michelle Chung: There's a lot to think about there because I'm trying to find a good analogy for it. And how, how like language about other other topics is molded to who's telling the story. And I think that's like where the word imposter syndrome...like that's how that was formed as well. And I totally agree with what she says that, like that the word imposter gives the power to the to the person that's like, telling you you are the imposter.

Mary Riker: No, I get what you're saying.

Mary Riker: Yeah, that does make sense and I think that's the case in a lot of social situations where people who are in power, define what's wrong with the system, you know. So shifting the conversation back to the group or the person that isn't in power, and using maybe a different way to say, their concerns or their feelings might change the conversation and make them feel more accepted and more heard.

Michelle Chung: And there's something about a being called a syndrome like it's a pathology, something that's wrong with the person that's feeling it is, yeah, like, that's....

Mary Riker: ...a linguistic concern...

Michelle Chung: Right. It's a shared experience, like everyone has felt imposter syndrome. So therefore, it's like not typical, right? Like, that's what like a syndrome is right? Something that's not typical, even though everyone feels it.

Mary Riker: So how do we change that usage to make it more "we all have this shared experience of feeling that way," and not like singling yourself out in that you feel alone in a certain experience?

Michelle Chung: Yeah, yeah. The language just isn't there yet. And that's something that we need to think about more

Mary Riker: Absolutely. Let's go back to Steffi with some solutions.

[MUSIC]

Mary Riker: What do you think's the best way to combat that systemic sort of "let's only have white men in this field, or let's only promote white men in these certain fields."

Stephanie Diem: I think it's to call out things like all white male panels or manels. If someone's looking for speakers, you give people that are knowledgeable, you know, in the subject and represent the diversity of your field. It's the affinity groups like WISE or something like that, building those connections and those networks too, and that support that's built in there.

Mary Riker: Another thing that you said is the minorities and women in your field are doing really interesting kind of unique work. When you include different types of people, you include the spheres that they have around them and the variables and concerns in their lifestyle that they have. Would you say that contributes to these kinds of new unique things that minority groups or women may be doing?

Stephanie Diem: Well, it's diverse perspective, that kind of enrich your field. And and there's actually studies out there that show when you have a diverse research group, they're quicker to solve problems and to come up in with innovation. So it's acknowledging what's already been shown in scientific research. Right?

Mary Riker: So we have that research. And we're scientists, right? So theoretically, in the perfect world, that would translate over and we'd see these very diverse groups in science, right? Yeah. But we don't see that. What do you think the barriers are to that?

Stephanie Diem: I mean, oftentimes, people choose people to be on their team that look like them or something like that. Also, I will step back and acknowledge part of the reason why I chose engineering was because I just wanted to do science and math, I wanted nothing to do with politics, nothing to do with, you know, human interaction, English classes. So I would think we need to be better, you know, acknowledge that we should be well rounded people, you know, to learn about other subjects and humanity, and you know, things like that.

Mary Riker: After getting your PhD and being one of the only women in that program to get it, how did you feel? Did it make you feel more accomplished, that you were one of the few women in this program to actually receive that?

Stephanie Diem: I think, for me, I don't take the time to acknowledge something when I've achieved it.

Mary Riker: Okay.

Stephanie Diem: I'm always focused on "Okay, so I did this. Now I gotta get this milestone," right? And so I think I need to be better still at acknowledging what I've accomplished, saying that. So for me, I was very proud because originally to be honest, they told me I would fail out of that program. So the fact that I made it through that program, I was so proud of myself for that. I'm speaking from my perspective, I feel like I always have to achieve something to prove myself. I think that's just always kind of in the back of my mind, whether I acknowledged it or not. And it is because people question why I'm in certain spaces, right? So I think it's just predisposed to do that.

Mary Riker: So moving on from so you've just completed your PhD, you've done this really difficult program at Princeton, which is so, so impressive. Where did you go after that?

Stephanie Diem: I was hired as a staff scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Mary Riker: And what did you do in that role?

Stephanie Diem: So for there, I did microwave heating and efficient experiments around the world.

Mary Riker: Wow.

Stephanie Diem: Yeah. It's pretty fun. Um, I did some modeling to have like, we inject cold kind of pellets of fuel, into plasmas. That's the fuel for fusion to kind of get them to release a little bit of energy at a time. So I could did kind of modeling for that and different experiments. Yeah.

Mary Riker: Were there other women that you could work with in that program? Or was it still this idea, like 10% women or less?

Stephanie Diem: Oh, it was less.

Mary Riker: Okay.

Stephanie Diem: There was only one other in the program. And then she retired. And then I was just me. And then I think at one point we had when I, you know, before I came here, if there was a woman who was a postdoc, but yeah.

Mary Riker: Okay, so what was that like being the only woman in a group of, I don't know, how many people did you work with other laboratory?

Stephanie Diem: So in our division, it was like 40 to 60. It was very, very, very lonely and really hard. So I think what made it easier was I actually went on long term assignment to a lab in California. That's a fusion lab, at General Atomics called the D3D National Fusion Facility. And they had more women there. And so I had a network, and we would have lunch together hanging out together. And so that builds, you know, camaraderie that, you know, resilience and things like that. And that was super important to me.

[MUSIC]

Michelle Chung: Let's cut in here again, for a minute to think about this. Can you even imagine what it's like to be one woman out of 40 or 60 people?

Mary Riker: I mean, I really can't. It's so surprising to me that that's still occurring. I mean, she wasn't a postdoc or working in that role that long ago. So it's still very, very surprising to me that we see this happening, even if her field is so male dominated. Because one out of 40, or one out of 60 is a much lower number than one out of 10.

Michelle Chung: Right? Yeah. It, yeah, just sounds so isolating. And it's crazy, just like to think of she had like one more person like to go from no camaraderie to, to someone that you can rely on to really make a difference.

Mary Riker: Just to have one more and make an impact, right? I agree with you. Let's talk about why Steffi came back to UW-Madison next.

[MUSIC]

Stephanie Diem: I found that I, while I liked working at a national laboratory, in a big collaborative environment, I really missed the innovation that happens at the universities, I really missed a couple of you know, a couple of times, I was able to mentor students. And I found that really great because I learned a lot from them through the process, just the way you know that their ideas are fresh and new. And I found that really brought in more creative aspects to research. So, I wanted more of that. When I was an undergrad here, I had some of the best support from some faculty in the College of Engineering. And to me, it's amazing that I had them supporting me as an undergrad, they really pushed me to get to a place where I didn't think I could, and now I get to be colleagues with them. And that's kind of wild.

Mary Riker: I mean, yeah, that's that full circle history. Really, really cool. Can I ask you, is there anything specific that the program you were in at Madison, and that you now work in? Is there anything specific that they did to kind of push you but also make you feel sort of included?

Stephanie Diem: So when I was an undergrad, I actually took a couple of graduate level classes and plasma physics. And some people could have just laughed at me and been like, "Why are you taking this graduate level class, you're an undergrad?" but they just treated me like a grad student. And to me, that made me feel like, okay, I think of these people, it's the smartest people I know, and they're not doubting my ability. And I really appreciated that. I just liked that, though, the way that they treated me with respect, and they believed in me, I really, I just want to be that person for other people.

Mary Riker: Yes. What, if anything, would you like to see changed in the future for women in your field, or your sub field, that works too.

Stephanie Diem: Oh, changed in our sub! Because I do a lot of work in our sub field. And I'm gonna say this from the perspective, I mean, yes, I identify as white woman and you know, things like, I'm from that demographic. So I have those experiences. But really, what I would like to see changed is people listening to minoritized populations, when they're bringing about an issue or something, not just saying, "Here's how we address this problem that you're complaining about," and then not listening to the minoritized population, when they're telling you the solution.

Mary Riker: Would you give any specific advice to young women who are entering your field?

Stephanie Diem: I would say if you get stuck or you're, you know, experiencing harm or something like, that tell someone. You don't have to shoulder it by yourself, you don't have to put up with that. You can tell a faculty member and and really don't put up with it. I put up with so much for so long. And it kind of made me miserable. It was like all these thorns in my side, a lot of the microaggressions, a lot of the sexual harassment, and I just thought I was supposed to sit there and take it. And it just kind of made me like a shell of a person. And when I started addressing it, and calling it out, I found it empowering. It started to make some changes. And I was happier.

Mary Riker: Would you say that for academics or people who are older, maybe, having those spaces to go be with women or people who look like themselves is empowering?

Stephanie Diem: I would say its very helpful, yeah, it builds community. So on campus, I mean, we have the "Ooey-Gooey Chocolate Cake Lunch" once a month!

Mary Riker: Can you tell me what this is? I don't know what this is!

Stephanie Diem: It's women faculty who get together and eat cake!

Mary Riker: Oh my gosh! I love that.

Stephanie Diem: It's things like that, that I find helpful. So in my subfield, on campus, there are four of us, three faculty and one scientist. And we occasionally get together. I think that's very helpful.

Mary Riker: Building your own personal support network. How do you have the continuing energy for this?

Stephanie Diem: Oh my gosh, for what?

Mary Riker: To, to be a scientist, I assume you do research, your own research, teach, be open to working on issues of diversity and inclusion in your field, and having experienced all these things in the past, how do you not become angry about it, I guess? How does it not just shut you down? How do you have the continuing energy to maintain doing all it?

Stephanie Diem: That's a great question! How did you say it? How do you not let it make you angry?

Mary Riker: Yeah.

Stephanie Diem: It makes me angry. And I acknowledge that. And I let myself feel angry. And then I find people to help me. The other things I do is I do outreach too. I find that helps me a better scientist too. Explaining what we do to the public, because ultimately what we do, clean energy, is for everyone, and making them part of the process, is what I do. So I helped launch the US Fusion Outreach Team. We are a grassroots organization to lower the barriers for outreach in fusion. It started as a Google Group and we have a lot of presentations that people can use. But then what sprung out of that was this website called the US fusion energy dot org. And part of its informing the public and making them a part of the fusion movement, and also diversifying the workforce by anyone that is interested in fusion can find jobs. So its kind of branching out and bringing the public in too.

Mary Riker: What other kinds of outreach do you do? Anything specific for minorities and women?

Stephanie Diem: So I have done workshops, Expanding Your Horizons, I've done that one, and then I've participated in uWhip, American Physical Society Undergraduate Women in Physics, I've done work with that.

Mary Riker: And that helps you feel like you're making this change less angry, I guess?

Stephanie Diem: So, for me, its putting in the effort, whether that is being trained as an ally, pushing for things in your department for equity and inclusion. I think any time I'm doing outreach to bring people into this field, it's got to be something that's welcoming for them, so its both.

[MUSIC]

Michelle Chung: How do you feel after, after talking with Steffi?

Mary Riker: I felt, really, kind of honored that she shared all this stuff with us, honestly. I really liked her take on balancing and recognizing your emotions and then doing something with that. Not to just put it away and hide it in a box and act like a robot, which sometimes I think engineers sometimes take that step a little too far. So her recognition is really powerful to me. And I think she is definitely a role model. She's going to change her students life in a positive manner just by being who she is, so authentically, it's really inspirational and I really, really enjoyed talking to her.

Michelle Chung: Mhm. And she was so concise in her advice, and she really gave us some action items on how you can genuinely feel better and what worked for her, which I think is awesome. And just throughout that whole conversation that you had with her, truly emphasized listening to people, respecting people, and believing in people, and those are the core, it seems like those are the core things you can do to make people feel like they belong.

[MUSIC]

Mary Riker: Thanks for listening to our show today. We're your hosts, Meg Riker..

Michelle Chung: ...And Michelle Chung.

Mary Riker: This show was produced by us and Mark Griffin, and edited by myself and Mark Griffin. Thanks again to our guest, Dr. Stephanie Diem, Assistant Professor of Engineering Physics here at UW-Madison.

Michelle Chung: And see you next time on Propelling Women in Power.

[MUSIC]

Mary Riker: What would you consider to be your superpower?

Stephanie Diem: Oh, my superpower? Oh gosh, can I say shoes? Like my shoe collection. I'm just gonna say it!

Mary Riker: That's awesome! What types of shoes do you have or do you most enjoy?

Stephanie Diem: Um, so, my favorite brand is Fluevog, and they're amazing, and I love them.

Mary Riker: When I was a kid, I used to have and wear like neon, bright neon, converse and stuff like that. Shoes are great.

Stephanie Diem: That's awesome!