When extreme weather hits, energy grids can suffer, with power outages displacing communities from essential services. However, microgrids can be a solution. In this episode of Watt's Up, Wisconsin, we break down what exactly microgrids are, and how they create community resilience in the wake of extreme weather.

We talk to Henry Hundt, UW–Madison graduate and sustainability lead at Hoffman Planning, Design, & Construction, about how microgrids play a role in our net-zero energy future. Then, we turn towards Bayfield County and talk to William (Bill) Bailey of Cheq Bay Renewables and Mark Abeles-Allison, Bayfield County Administrator, to see how a microgrid provided their community resilience.

Do you have a question about energy in Wisconsin? Ask the Wisconsin Energy Institute at communications@energy.wisc.edu or tweet us and tag #WattsUpWI.

Listen to Watt's Up, Wisconsin? on Apple podcasts, Spotify podcasts, Google Podcasts, Youtube, or anywhere you find podcasts.

Guests

Henry Hundt, Sustainability Lead at Hoffman Planning, Design & Construction

Henry Hundt, Sustainability Lead at Hoffman Planning, Design & Construction

Henry holds a master of public affairs and energy, analysis, and policy certificate from University of Wisconsin–Madison. His master's work focuses on techno-economic modeling for energy storage and microgrids.

William (Bill) Bailey, President of the Board of Directors at Chequamegon Bay Renewables, Inc.

William (Bill) Bailey, President of the Board of Directors at Chequamegon Bay Renewables, Inc.

Bill began installing renewable energy systems in 2008 for his home and commercial greenhouse, Bailey's Greenhouse. Since then, Bailey's Greenhouse now supports local efforts in renewable energy, the local food movement, native plant, and pollinator plant initiatives.

Mark Abeles-Allison, Bayfield County Administrator

Mark Abeles-Allison, Bayfield County Administrator

Mark has served as the County Administrator of Bayfield County Wisconsin since 2001. He has worked projects including utility automation, park and river walk development, walkable community development, and sustainable energy generation.

Credits

Britta Wellenstein, Host

Britta Wellenstein, Host

Britta is a Wisconsin Energy Institute communications intern and UW–Madison undergraduate majoring in Life Sciences Communication and Environmental Studies.

This episode was produced by Britta Wellenstein and Michelle Chung.

Theme music by Eden Comer.

Transcript

Britta Wellenstein: The sky darkens as thunder churns in the clouds.

[thunder]

You hear the rain roll in the wind, pick up and push trees around outside and then

[buzzing hum]

The lights flicker and the power goes out. We've all been in one. A fallen tree from a storm knocks down your power line and you're stuck without power until the storm rolls away and someone can come to fix it.

But power outages happen from more than just storms. From thunderstorms to extreme heat or cold, extreme weather events can disconnect homes and communities from the grid. This not only disrupts our daily life, but it puts lives at risk. But what if communities or buildings could generate their own power, allowing lights to stay on if the power goes out by creating something separate from the larger grid?

A microgrid.

Today on Watt's Up, Wisconsin, we'll look at how many communities stay resilient when the grid fails, answering the question, what are microgrids?

[MUSIC]

[light switch]

Britta Wellenstein: You're listening to Watt's Up, Wisconsin, brought to you by the Wisconsin Energy Institute, where we explore your questions on energy in Wisconsin.

[cow moo]

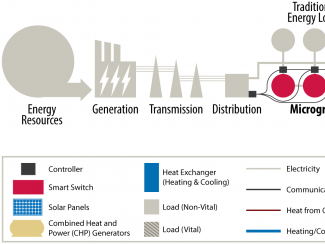

Britta Wellenstein: I'm communications intern Britta Wellenstein. Before we can even begin to understand microgrids, we have to understand what the energy grid actually is. According to the Department of Energy, the grid is a transmission system. All those power lines bordering our roads? Those interconnected lines make up the grid, transporting electric energy from the point of supply like power plants to customers like us.

Wisconsin is in the Midwest electric grid managed by the Midcontinent Independent System Operator. Microgrids are just a smaller version of these grids. Instead of transmitting power from a far off power supply, they generate their own electricity and have the ability to disconnect from the larger energy grid.

Henry Hundt: Definition making grid is a user are users so a building or a community that has some amount of onsite generation. So solar PV, wind, gas, propane, diesel generators that can operate autonomously from the grid.

Britta Wellenstein: That was Henry Hunt, a UW–Madison La Follette School of Public Affairs graduate. Henry worked in Morgan Edward's Climate Action Lab and the Office of Sustainability at UW–Madison. He now works for Hoffman Planning, Design, & Construction as a sustainability lead.

Henry Hundt: Importantly, microgrids are often not on an island to themselves and should be interconnected to the larger grid, especially for the lower 48. Usually when we think of microgrids in Lower 48, you often are still connected to the local distribution network and that autonomy is enabled by onsite generation now is also enabled by onsite storage of variable energy sources like PV, so those are batteries and often will still include or can–they do not need to be–can include an existing diesel generator.

Britta Wellenstein: Like Henry said, microgrids can take a variety of forms, both in the energy source, in size and function, and in the type of battery. Microgrids are actually all around us, making sure vital resources stay running and power outages.

Henry Hundt: As we know from school districts, as we know from every dairy farm that I've ever known has a diesel generator onsite. Because if the grid goes down and at the end of a very rural line, they still need to milk, otherwise their animals are going to suffer. And so they often will have a diesel generator. So they are already running a small microgrid in the sense.

Britta Wellenstein: And like similarly, I've heard hospitals express the same way, like they need to be running, so no matter what, if something goes wrong, they have something else to put them back up.

Henry Hundt: Yes, exactly. It is those places that provide critical infrastructure in times of natural disasters that often have them as well.

Britta Wellenstein: Outside of critical infrastructure, microgrids are also seen as a vital part of net-zero carbon goals and a renewable energy future. As communities start electrifying their buildings and adding renewable sources of energy like solar panels or geothermal energy, they are close to becoming microgrids, and new incentives are making it more economically viable to turn these into microgrids.

Henry Hundt: With Inflation Reduction Act, with the direct pay incentives for geothermal and PV and microgrid controllers, which is the kind of the brain that sits with the battery and tells it what load should be service during an outage, where the power should flow from, from the battery or for the variable generation of the PV, or if you have another generator. All those costs are for non-profits are eligible for direct pay, which means that allows them to utilize all this tax incentives that only have been available for non-profits.

And that is to say microgrids are becoming far more economic as a possible solution, along with net zero energy goals. And I'm trying to tie this to net zero energy at a facility level or a building level because to reach net zero energy, you have to produce at sometimes in the year way more energy than you can utilize depending on your design.

That's because if you are electrifying your HVAC, you're going to see really steady use. A lot of that heat through heat pumps will be added load that you didn't necessarily have before, if you're using natural gas or propane, and depending on the amount of air conditioning you need, you maybe, you're adding air conditioning capacity you didn't have before.

So if you have this really oversize system for certain times of the year, it can make a lot of sense to add some batteries. So you can start to perform energy arbitrage, moving the energy from what is produced to off hours, and then you're almost all the way there to a microgrid. You add a controller and you are able to operate autonomously at certain times of the year indefinitely.

[MUSIC]

Britta Wellenstein: The ability for a community or a building to keep up operation and provide energy in the event of an outage creates a more resilient system. This resilience is key to microgrids, especially as power outages become more and more common. A 2022 Climate Central report found that power outages increased roughly 78% during 2011 to 2021 when compared to the decade before.

83% of power outages are caused by weather related events. These events, like floods, heatwaves, wildfires and ice storms are growing in intensity and frequency, putting stress on our electrical grids. In cold and heat related events, more people use electricity to heat or cool their homes, which can override the system and cause outages. This summer, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation reported that Wisconsin's electrical grid could face supply shortages from increased electrical demand and extreme heat events.

To battle extreme weather and prevent outages many communities in Wisconsin are turning to microgrids as a solution. One such place is Bayfield County in Northern Wisconsin.

Bill Bailey: My name is Bill Bailey, president of Cheq Bay Renewables. We are a local nonprofit. We've been successful developing projects in our local area. We basically work on Bayfield County and Ashland County. We work with both tribes that are up here, Red Cliff and Bad River.

Mark Abeles-Allison: My name is Mark Abeles-Allison, the county administrator with Bayfield County. Beaver County has a long history with energy from a conservation, renewable and alternate energy and now toward resilience.

Britta Wellenstein: Bayfield County and much of northern Wisconsin has experienced frequent power outages and millions in damages during extreme flooding events. These storms cut off power to essential services like the health department, the sheriff's office, and the 911 dispatch. The county also had an aging diesel generator that needed to be replaced. Installing a solar microgrid provided a solution to both of these problems.

Bill Bailey: The reason why the microgrid became the solution was basically because it was a solution. Gave resiliency to the county. One of the buildings is the courthouse. The other one is the jail. It's very important. It's got the 911 system. It has a 911 system for two counties. So it's essential that these buildings retain power. And if you have a backup generation that that's not dependable and you lose your 911 system during an emergency, you're really messed up, so this resiliency project, the microgrids and the batteries, just really enhanced the whole ability of the county to provide these essential services.

Britta Wellenstein: For the microgrid, why did Bayfield choose solar as the power supply? Because I've heard other microgrids that still use diesel generators, but why was solar the option for Bayfield?

Bill Bailey: These are your answer to that as far as the way we define a microgrid. If it doesn't have Renewable Energy, incorporated we don't consider it a microgrid. We can you know, it's got fossil fuel backup generation, but that's in our definition is not a microgrid. It has to have renewable energy. It can incorporate fossil fuel backup generation. In fact, the three of them work really well together. The solar, the batteries and the backup generation work very well together. But if you take the renewable energy component out of it, it's not a microgrid, in our opinion.

Mark Abeles-Allison: As Bayfield county went carbon neutral for our county facility electrical usage. That means that a combination of utility, solar and wind, and county solar put us in that position. So our our total carbon footprint from county facilities for electricity usage is is now carbon neutral.

Britta Wellenstein: So you have solar and even if there's not a power outage, it's still running. Is that electricity that the solar is generating when there's not a power outage and you're still connected to the grid just being put back into the grid and spreading throughout the county? Or is that going right to the facility?

Mark Abeles-Allison: One of the interesting things is oftentimes in the summertime, the right now that the solar is at our annex or jail facility and will produce 150% of the energy demand and the rest was sent back to the state. So now we're combining the two facilities, both the courthouse and the jail is going to be on the same circuit.

That energy flow will be able to go to the courthouse. So hopefully there will be times when we'll be 100% both, for both facilities, 100% solar, which will be very exciting.

Britta Wellenstein: But the Bayfield microgrid has 116 kilowatt solar system with battery storage. Solar panels have been placed alongside highway garages and onto the jail complex. This system not only provides resilience in the face of power outages, but provides economic incentives as well.

Bill Bailey: To put a number to it, the generator, the backup generator that's aging that had to be replaced would have been about 150, 160, maybe even $170,000 investment. And instead of putting that money into a piece of equipment that could be a stranded asset down the road, instead, the county decided to put it into a new technology, that that's more future proof.

Mark Abeles-Allison: That's one of the unique things. Microgrid folks use the terms integrated and smart. You'll see out in other areas of the country that the new utility pricing is changing rapidly depending on when you use energy and with the battery and with the solar and with the generator. There's an opportunity to kind of schedule that energy usage or use the–schedule that battery usage to minimize or reduce utility costs.

In addition, there's a peak load shaving that can be done. A lot of folks say that 30% of your bill is just those peaks, those peak demand periods. And with the battery of it, we can kind of shave that off and cover those peaks, those three, four or five second peaks as an engine starts up or a motor starts up. With the battery covering that, we're hoping to see some significant energy savings.

Britta Wellenstein: What was the community reaction? Were they very supportive of this project? How did they view this?

Mark Abeles-Allison: I think the key thing is that the idea of resilience with essential services, knowing that our sheriff's office, our health department, our human services, our jail, our dispatch, that all those can comfortably continue operation during a disaster or emergency periods is well-received. Sometimes energy is a little bit behind the scenes and people don't see it. You only see it when you don't have it.

This is our way of looking to the future to better ensure continued services.

Bill Bailey: I might add one one thing to that, and that is even though the main purpose of a microgrid is always resiliency, there also has to be an economic factor that's got to make sense. And so because of that, we didn't have to replace that generator because that was like a mandatory expense if you chose option B. It made the economics work out.

And that makes it an easier sell to the various committees, to the full county board, to the public, because it does make economic sense, too. So, yes, all the all those other benefits: the resiliency, the carbon reduction, all those are great, but it also has to make economic sense. And so we try to put all that together in one package.

Britta Wellenstein: Bayfield is not the only example of microgrids in the state. The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, the Village of Boaz, an organizations in Appleton and Middleton, have also installed microgrids. These communities are working towards resilience and cleaner energy futures. Bill hopes they can take the work they've done in Bayfield and continue to spread it throughout the county and state.

Bill Bailey: We have our second microgrid under construction at County Highway Garage. That's just beginning now. And then we have submitted grant applications for 23 more microgrids spread throughout, throughout the county through the Department of Energy grant that's actually being submitted by the state of Wisconsin. We have learned from the jail courthouse microgrid, which is a fairly large microgrid. We've scaled it down a little bit in the Washburn Highway garage.

We've come up with a replicable model that will go to five other county highway garages, but it'll also be scaled down even farther to towns. In Beaufort County, we have six or eight other communities in Bayfield County that are installing microgrids or want to install microgrids in their town halls and town garages, essential services. And also we're working with Red Cliff to develop two large microgrids there in their health clinic and a road highway garage building that they're building.

So this is definitely a replicable model once Bayfield County gets in place. And because of this grant application has been submitted by the state of Wisconsin, we're going to work closely with the state to make sure that this model, this information gets gets put out throughout the state and can be replicable throughout the state.

Britta Wellenstein: Thanks for listening in. Do you have questions about energy? Wondering how new energy solutions are taking off in Wisconsin? Let us know by sending an email at communications@energy.wisc.edu or tweet @UWEnergy and tag #WattsUpWI.