Here is some of the news, research, and challenges to the status quo we’re using to inform our own actions and words in making UW–Madison a more welcoming space for people who identify as BIack, Indigenous, or People of Color. The goal is to educate ourselves – and each other – so we can do better. Let us know if you have a suggestion to add to this list.

Energy and Climate Justice: Reading List

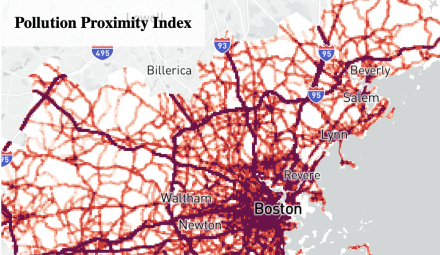

People of Color Breathe More Hazardous Air. The Sources Are Everywhere.

Over the years, a mountain of evidence has brought to light a stark injustice: Compared with white Americans, people of color in the United States suffer disproportionately from exposure to pollution.

Now, a new study on a particularly harmful type of air pollution shows just how broadly those disparities hold true. Black Americans are exposed to more pollution from every type of source, including industry, agriculture, all manner of vehicles, construction, residential sources and even emissions from restaurants. People of color more broadly, including Black and Hispanic people and Asian-Americans, are exposed to more pollution from nearly every source.

The findings came as a surprise to the study’s researchers, who had not anticipated that the inequalities spanned so many types of pollution.

“We expected to find that just a couple of different sources were important for the disparate exposure among racial ethnic groups,” said Christopher W. Tessum, an assistant professor in environmental engineering and science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, who led the study. “But what we found instead was that almost all of the source types that we looked at contributed to this disparity.”

Coming in 2022: exhibition on environmental justice

The advantages of a well-protected environment—and conversely, the hazards of a damaged one—have rarely been evenly spread. Instead, both historically and in the present day, access to a safe, healthy, and pleasant environment has been controlled not only by where you are, but also who you are. Public and private designs for green spaces, pollution controls, and remediation projects have been lavished on communities already at the center of power. Meanwhile, the places where the environment has been turned into a sacrifice zone are most likely to be the same places where poor families, immigrants, and people of color find themselves living and working.

What links these uneven environmental and social patterns together is geography. Sometimes they quite literally map onto one another. For this reason, maps can provide powerful tools for understanding—and challenging—these injustices.

Wisconsin regulators seek workforce diversity, energy burden data from utilities

For the first time, Wisconsin regulators are requiring utilities to report on the diversity of their workforces and suppliers, as well as the portion of household income their customers spend on energy.

The Public Service Commission announced Monday that all 609 regulated electric, gas and water utilities must include demographic information on their employees and boards of directors in their annual reports to the agency.

The PSC is asking for data on race, ethnicity, gender, disabilities and veteran status for workers at all investor-owned and municipal utilities.

In addition, investor-owned utilities with at least 15,000 customers must provide information on their suppliers, including procurement goals and actual spending with businesses owned by minorities, veterans, women, LGBT individuals or people with disabilities.

Rise Up Midwest: Energy Equity

How do we achieve a more equitable energy economy? If you ask Denise Abdul-Rahman with the NAACP, she’ll kindly tell you that we need a system that increases employment opportunities and decreases pollution externalities. We need a system that creates investment opportunities for those in need instead of long-term dependencies. We need a system that prioritizes raising people out of poverty above raising profits for the few. She’ll say it starts with dialogue – listening to the communities in need and valuing community knowledge. And then she’ll ask you to re-imagine how a new clean energy economy can work for all.

Biden’s EPA nominee vows ‘urgency’ on climate change

Michael Regan, President Biden’s choice to lead the Environmental Protection Agency, told lawmakers Wednesday that he would “restore” science and transparency at the agency, focus on marginalized communities and move “with a sense of urgency” to combat climate change. Facing a Senate panel where half of the members are Republicans wary of the EPA’s authority and its reach into much of American life, Regan appealed to a collective sense of duty.

Tony Reames named to Five-member Michigan Climate Justice Brain Trust

Dr. Reames joins a panel of climate and environmental justice experts named to develop a justice and equity-based framework for the development and implementation of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s MI Healthy Climate Plan, which calls for a transition to a carbon-neutral Michigan by 2050 that includes communities disproportionately affected by climate change. The five-member Climate Justice Brain Trust will help guide the Office of Climate and Energy’s work in identifying barriers that impede environmental justice communities from realizing the benefits of the energy sector’s transition to cleaner energy sources. It will provide guidance on appropriate climate adaptation, mitigation and clean energy investments from a climate justice perspective.

Why energy justice is a rising priority for policymakers

Communities of color bear the brunt of energy-related social, economic, and health burdens. U.S. Department of Energy's deputy director for energy justice Shalanda Baker explains how energy justice can help.

As the U.S. begins to transition away from fossil fuels, policymakers are confronting a host of social, economic, and health burdens caused by the existing energy system.

Innovators in the energy space are examining these issues through the lens of racial and social justice, acknowledging that communities of color often bear the brunt of such problems — such as higher utility bills, heightened susceptibility to air and water pollution, and increased vulnerability to natural disasters.

This connection is giving rise to the growing field of energy justice, according to Shalanda Baker, the newly named deputy director for energy justice at the U.S. Department of Energy and author of “Revolutionary Power: An Activist's Guide to the Energy Transition.”

“Energy justice specifically focuses on the ways communities should have a say in shaping their energy futures through policy involvement … as well as ensuring that the policies that we're developing, particularly in this moment of energy transition, don't have unequitable impacts on the most marginalized communities,” said Baker, speaking last fall at a presentation hosted by the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative.

Baker, a professor of law at Northeastern University, is co-founder and co-director of the Initiative for Energy Justice, which aims to deliver equity-centered energy policy research and technical assistance to policymakers and frontline communities. She spoke with

faculty co-director of the Sustainability Initiative, on ways to place equity at the center of energy policy design.

Funding challenges limit minority-owned businesses’ access to energy efficiency

Securing capital is a big challenge for many Black- and other minority-owned businesses. Whether through outright discrimination or more subtle bias, many companies face a disadvantage in a financial world where personal relationships can make or break a deal.

It’s a particularly vexing problem when it comes to energy efficiency improvements, which can save money and in many cases more than pay for themselves. That dilemma becomes even more pressing as the pandemic continues.

“Capital has become an issue for almost every Black-owned business, small and midsize businesses especially,” said Carla Walker-Miller, founder and CEO of Walker-Miller Energy Services in Detroit.

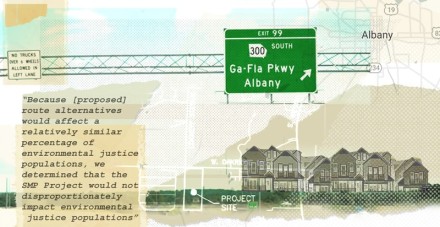

Are pipeline companies buying justice?

The officers who cuffed and arrested Cindy Spoon wore badges and gun belts. At least one wore a ball cap marked "POLICE." But these weren't traditional beat cops. They were Louisiana state probation and parole officers. Just as importantly, they were in the pay of Energy Transfer LP, the company building the Bayou Bridge pipeline, the project Spoon was protesting. Spoon paddled through the Atchafalaya Basin to a work site in a canoe that day — Aug. 9, 2018 — possibly to put herself in the way of construction. She believed she'd found a way to do that while staying within the law — by staying on the water.

Postdoc Diversity and Inclusion Forum: A Diversity of Stories

The UW-Madison Postdoctoral Association Diversity & Inclusion committee is planning a virtual forum (date to be determined) aimed at highlighting diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice issues and challenges faced by UW-Madison’s postdocs from underrepresented groups. The committee is soliciting personal narratives and campus policy recommendations from UW-Madison postdocs and would like to hear from you!

Cultivating inclusive instructional and research environments in ecology and evolutionary science

As we strive to lift up a diversity of voices in science, it is important for ecologists, evolutionary scientists, and educators to foster inclusive environments in their research and teaching. Academics in science often lack exposure to research on best practices in diversity, equity, and inclusion and may not know where to start to make scientific environments more welcoming and inclusive.

Minority students share their stories in science so others feel power of representation

When MJ Kirch went on an online field trip, she chose to take part in a session where a presenter working in a scientific field looked like her.

For MJ, it was important to show an interest in what an African American like herself had to say. Not surprising from a seventh-grader who has thought about being a surgeon but according to her mom, Tasha Kirch, is most interested in whatever career will allow her to help people.

“I know that it’s important for people who are underrepresented in any community ... to shine the light on them, so I thought that would be interesting to look at,” said MJ, who attends Core Knowledge Charter School in Verona.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency advisers quit over pipeline permit

A citizen advisory group at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) has collapsed following the regulator’s decision to issue a water-quality permit to Enbridge Energy for its Line 3 oil pipeline cutting through Minnesota. The bulk of the agency’s Environmental Justice Advisory Group has resigned in protest over the permitting decision, saying in a letter Tuesday to MPCA Commissioner Laura Bishop that “we cannot continue to legitimize and provide cover for the MPCA’s war on Black and brown people.”

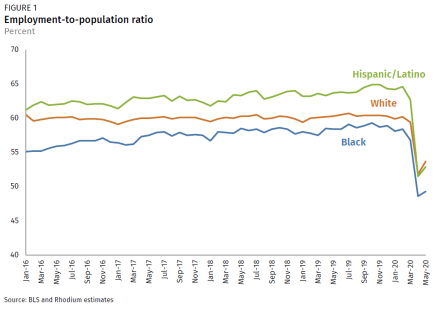

A Just Green Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic and recession have been particularly devastating for Black, Latino and Indigenous communities in the US. They have experienced COVID-19 hospitalization rates four to six times higher than white Americans, and current unemployment rates are significantly higher as well. Many of these same communities are disproportionately impacted by pollution, with significant public health and economic consequences.

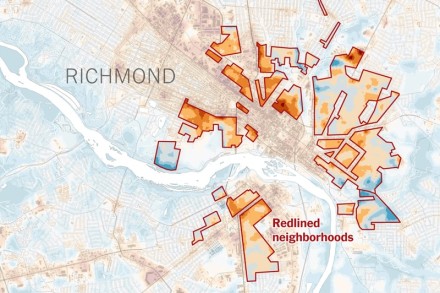

How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering

Redlining helped reshape the urban landscape of U.S. cities. It also left communities of color far more vulnerable to rising heat.

How electricity deepens the South's racial divide

Nationwide protests over racial injustice in recent weeks are stirring a fight against a deep-rooted energy gap in U.S. households: People of color pay disproportionately high electricity bills. Nowhere is the divide perhaps more obvious than the South, where the housing stock is old, summer heat is intense, building codes are weak and 40% of residents qualify for low-income energy assistance.

Two of Biden's veep contenders roll out environmental justice bill in Senate

Two top contenders to be Joe Biden's running mate have put forward a broad proposal to tackle the disparate impact communities of color face from pollution. Though many months in the making, the legislation from Sens. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) and Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.) comes as each is being seriously considered by Biden to join him on the Democratic Party's presidential ticket.

Extreme heat is worse in redlined neighborhoods

As you move through a city, you probably notice summer heat can be a lot worse depending on which neighborhood you’re in. This isn’t a coincidence. Maybe you’ve heard of the “urban heat island” effect, where cities are significantly hotter than surrounding areas. Urban landscapes, particularly roadways with black asphalt, large buildings, turn solar radiation into heat.

FERC faces environmental justice reckoning

Critics are calling on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to rethink its handling of environmental justice issues after its recent approval of a natural gas project in a predominantly Black community in Georgia that's still reeling from the coronavirus pandemic.

This prof is shedding light on energy injustice — and how to fix it

Tony Reames grew up in rural South Carolina in a “quintessential environmental-justice community,” as he puts it. After the textile industry collapsed in the 1990s, the region was saddled with both the state’s largest landfill and its largest maximum-security prison. It wasn’t until college that Reames, now an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, realized what had been going on in his own hometown — specifically, the way that social status shaped the physical landscape.