Here is some of the news, research, and challenges to the status quo we’re using to inform our own actions and words in making UW–Madison a more welcoming space for people who identify as BIack, Indigenous, or People of Color. The goal is to educate ourselves – and each other – so we can do better. Let us know if you have a suggestion to add to this list.

Energy and Climate Justice: Reading List

Detroit resident ‘leads with love’ while laying a foundation for neighborhood climate resiliency

On Belvidere Street on Detroit’s east side, Tammara Howard’s efforts to build a community space show what is possible with limited resources. Her project, What About Us?, provides a place for the community to gather, learn from one another and share resources.

Climate Anxiety Is an Overwhelmingly White Phenomenon

Climate change and its effects—pandemics, pollution, natural disasters—are not universally or uniformly felt: the people and communities suffering most are disproportionately Black, Indigenous and people of color. It is no surprise then that U.S. surveys show that these are the communities most concerned about climate change.

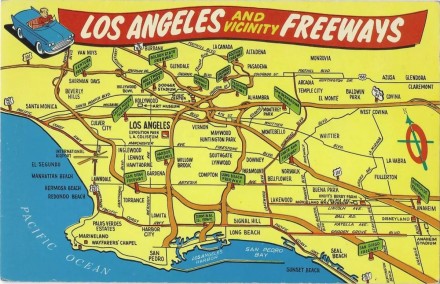

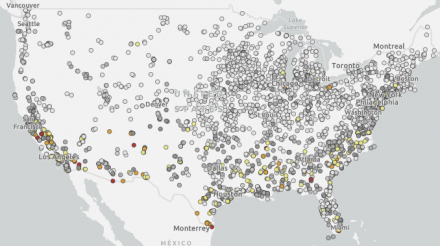

How white and affluent drivers are polluting the air breathed by L.A.’s people of color

The map shows how residents of whiter, wealthier communities disproportionately drive to work through lower-income Latino and Black neighborhoods, spewing pollution. Residents of those neighborhoods can’t do much about it.

UW-Madison's Black student enrollment has never exceeded 3%. Why does the school make so little progress, decade after decade?

UW-Madison didn’t start formally tracking race and ethnicity until the 1974-75 school year. Then, 2.2% of the student body identified as Black. In fall 2021 — with the overall student body more than 10,000 students larger — the percentage of students that identifies as "Black/African American only" remained at 2.2%. Another 1.4% of the student body identifies as Black/African American in addition to another race or races, for a total of 1,756 Black students on a campus of 47,936 in fall 2021.

DOE Releases New Equity Action Plan, Unveils Investments to Strengthen HBCU Opportunities in Clean Energy

In furtherance of the new Equity Action Plan, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) unveiled a commitment of up to $102 million in funding and support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and other Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) as foundations for world-class talent in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM).

Meet the social entrepreneurs shaking up solar

Projects like Redden’s Solar Stewards, Hansley’s WeSolar, and Othow’s EnerWealth Solutions are a one-two punch for climate change and racial inequality. Asked if it is crucial to address the challenges in tandem, they unanimously agree — yes.

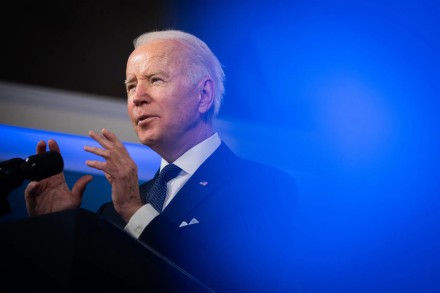

White House Takes Aim at Environmental Racism, but Won’t Mention Race

As a candidate and then as president, Joseph R. Biden promised to address the unequal burden that people of color carry from exposure to environmental hazards. But the White House’s new environmental strategy to tackle this problem will be colorblind: Race will not be a factor in deciding where to focus efforts.

University of Michigan comes to Detroit’s east side with inaugural ‘Sustainability Clinic’

The University of Michigan is opening a clinic on Detroit’s east side — but instead of offering flu shots and check-ups, this clinic aims to help residents cope with the vagaries of climate change. The University of Michigan Sustainability Clinic aims to “improve the ability of the City of Detroit and nonprofits serving the City to address the impacts of climate change on the natural and built environment, human health, and the city’s finances — while working to enhance sustainability policy and action.”

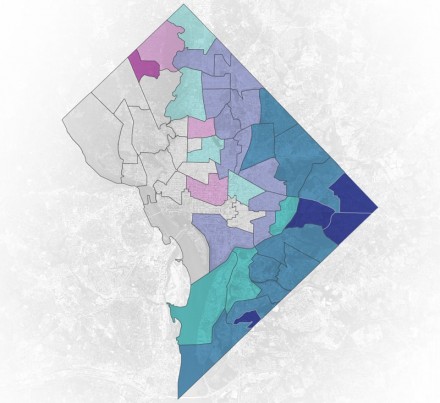

An Extra Air Pollution Burden

Like many cities in the eastern United States, Washington, D.C., has seen major improvements in air quality in recent decades. Levels of fine particle pollution (PM2.5) have declined by roughly 50 percent in the city since 2000 due to passage of a series of clean air laws. Cleaner air has yielded significant health benefits. The number of DC residents killed by diseases related to exposure to PM2.5 (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, lung cancer, and stroke) declined by 50 percent during that period, according to a new NASA-funded analysis of city-wide air quality and health data. However, the resulting health benefits have not accrued evenly.

Making Justice40 a Reality for Frontline Communitiesfor Frontline Communities

A new report by scholars from the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation, advised by environmental justice leaders, provides a framework that federal officials could use to maximize Justice40’s impact. The report analyzes state-level programs seeking to address environmental justice through investments in clean energy and climate change action — already underway in some cases, and in planning stages in others — and identifies shortcomings, ongoing challenges and successes that could help inform the implementation of Biden’s plan.

Offshore wind is America's new industry. Who will build it?

In New Bedford, where Vineyard Wind’s turbines will be assembled before being shipped out to sea, Dana Rebeiro is thinking about how to make sure the city’s Black, Latino and immigrant communities share in the industry’s promise. Twenty percent of New Bedford residents live below the poverty line.

College Was Supposed to Close the Wealth Gap for Black Americans. The Opposite Happened.

Black millennials thought college would help them get ahead. Instead, it is setting them back. The median net worth of households with Black college graduates in their 30s has plunged over the past three decades to less than one-tenth the net worth of their white counterparts, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of Federal Reserve data. The drop is driven by skyrocketing student debt and sluggish income growth, which combine to make it difficult to build savings or buy a home. Now, the generation that hoped to close the racial wealth gap is finding it is only growing wider.

Why Does Disaster Aid Often Favor White People?

The two cases were remarkably similar: Hurricane Laura sent pine trees crashing through the roofs of two modest houses not far apart in Southwest Louisiana. Neither homeowner had insurance, and each sought help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency. But that’s where the similarities end. Despite suffering roughly the same amount of damage, one homeowner, Roy Vaussine, who is white, got $17,000 in initial assistance from FEMA. The other couple, Charlotte and Norman Biagas, who are Black, got $7,000,

New Interactive Maps and Resources Empower the Public and Policymakers to Act on Environmental Justice

Today, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is publishing a new web resource with interactive maps and supporting materials that combine information on air pollution emitted by fossil fuel-fired power plants with key demographical data on nearby communities. The Power Plants and Neighboring Communities initiative advances the Biden-Harris Administration’s commitment to environmental justice by empowering the public and policymakers with information and tools to better understand the disproportionate impacts of air pollution in overburdened communities.

Tony Reames named Senior Advisor for DOE's Office of Economic Impact and Diversity

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) today announced additional Biden-Harris Administration appointees that have joined the team to deliver on President Biden’s bold climate goals and help build a more prosperous, equitable clean energy future for every American worker and family.

Tackling 'Energy Justice' Requires Better Data. These Researchers Are On It

Poor people and people of color use much more electricity per square foot in their homes than whites and more affluent people, according to new research. That means households that can least afford it end up spending more on utilities.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academies of Science, arrives as the Biden administration has said that it wants 40 percent of federal climate spending to reach poorer communities and communities of color, including initiatives that improve energy efficiency. Researchers have said better data on wealth and racial disparities is needed to make sure such plans succeed.

The researchers found that in low-income communities, homes averaged 25 to 60 percent more energy use per square foot than higher-income neighborhoods. And within all income groups except for the very wealthiest, non-white neighborhoods consistently used more electricity per square foot than mostly-white neighborhoods. The results were even starker during winter and summer heating and cooling seasons.

"This study unpacks income and racial inequality in the energy system within U.S. cities, and gives utilities a way to measure it, so that they can fix the problem," says Ramaswami, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University who's the lead investigator and corresponding author of the study. It's part of a larger project funded by the National Science Foundation to promote 'equity first' infrastructure transitions in cities.

Ramaswami says more investigation is needed to understand why this racial inequity exists. It's likely that utilities need to better tailor energy efficiency programs to reach underserved communities. She says there are also bigger, structural issues utilities have less control over, such as whether people own their homes or rent.

For the study, researchers looked at two cities: Tallahassee, Florida, and St. Paul, Minnesota. They combined detailed utility and census data and measured how efficient buildings were in specific neighborhoods.

"We were struck when we first saw these patterns," said Ramaswami.

The Princeton researchers also looked at which households participated in energy efficiency rebate programs. They found homes in wealthier and whiter neighborhoods were more likely to take part, while poorer, non-white households were less likely.

Ramaswami expects studies like this in other cities would reach the same results. They're already working with officials in Austin, Texas.

The information could be especially valuable as the Biden administration prepares to spend big on energy efficiency to meet the country's climate goals.

"From a policy perspective, that [better data] can help policy-makers better target communities for efficiency improvements and investment," says Tony Reames, assistant professor and director of the Urban Energy Justice Lab at the University of Michigan.

He's a leader in the emerging field of "energy justice," which holds that communities of color too often experience the negative aspects of energy – such as pollution and utility shut-offs – and don't share equally in the benefits, like good-paying energy jobs and efficiency programs.

Reames' lab is among those launching the Energy Equity Project. It plans to gather data "measuring equity across energy efficiency and clean energy programs." He says in addition to creating more equitable policies, that information can help communities advocate for themselves before utility regulators and government officials, and "ensure that investments come to their communities."

Making Science More Equitable and Inclusive

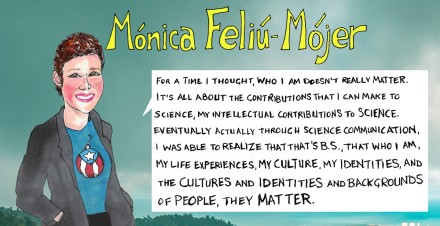

A big part of Mónica Feliú-Mójer’s life mission is to help use science communication as a tool for equity and inclusion, and she has certainly achieved this working with two non-profits called Ciencia Puerto Rico and iBiology. Mónica has spent over 15 years making science culturally accessible to different communities in Puerto Rico, and she is eager to continue building those relationships throughout her career. We talked to her about the “scientists without a title” she grew up around in rural Puerto Rico, work-life integration (not work-life balance), and how your cultures and identities absolutely matter in science, despite common belief.

Study shows how cities can consider race and income in household energy efficiency programs

Climate change and social inequality are two pressing issues that often overlap. A new study led by Princeton researchers offers a roadmap for cities to address inequalities in energy use by providing fine-grained methods for measuring both income and racial disparities in energy use intensity. Energy use intensity, the amount of energy used per unit floor area, is often used as a proxy for assessing the efficiency of buildings and the upgrades they receive over time. The work could guide the equitable distribution of rebates and other measures that decrease energy costs and increase efficiency.

Examining inequality in cities has been hampered by a lack of energy use data at fine spatial scales within cities. Until now, only Los Angeles has been able to use a data-driven approach to shine a light on where energy use inequalities exist, focusing specifically on the effect of income disparities. But according to new results reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, to truly understand and fully address energy use inequality, cities must take an even more nuanced approach—one that unpacks race-related disparities from income. As the authors report, examining the issue solely through the lens of income risks missing significant race-related inequalities that exist beyond income effects.

“Often, in discussions about social justice, people sometimes ask, ‘Oh, how do you know it’s a race effect and not ‘just’ an income effect?’” said Anu Ramaswami, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University and the study's lead principal investigator and corresponding author. “This paper actually shows you the data, that there’s a structurally linked income-race effect, and an additional race effect even within the same income group.”

Global heating: Study shows impact of 'climate racism' in US

A new study says that black people living in most US cities are subject to double the level of heat stress as their white counterparts. The researchers say the differences were not explained by poverty but by historic racism and segregation. As a result, people of colour more generally, live in areas with fewer green spaces and more buildings and roads. These exacerbate the impacts of rising temperatures and a changing climate.

U-M Energy Equity Project to Develop First Standardized Tool for Driving Equity in Clean Energy Industry

Despite widespread calls for a just transition to cleaner, more resilient energy systems, there isn’t a standardized measurement framework for evaluating the equity of clean energy programs. As a result, utility administrators, regulators, and energy advocates have been judging equity on an ad hoc basis. The Urban Energy Justice Lab at the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability (SEAS) today announced a new program aimed at addressing this gap, which will measure whether clean energy programs are being distributed equitably to those who need them most.

The Energy Equity Project—a partnership between SEAS and the Energy and Joyce Foundations—will create a standardized approach to collecting and tracking data to improve equity in clean energy programs. The Equity Measurement Framework will be the first of its kind to assess equity in clean energy policies, programs, and investments, including how easy it is to access clean energy services in frontline and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities that are burdened by disproportionately high energy costs and pollution. This comes at a critical time, given the Biden administration’s increasing focus on environmental justice. The project will dovetail with the administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which pledges to deliver 40 percent of climate investment benefits, including weatherization, retrofits, and renewable energy, to disadvantaged communities.