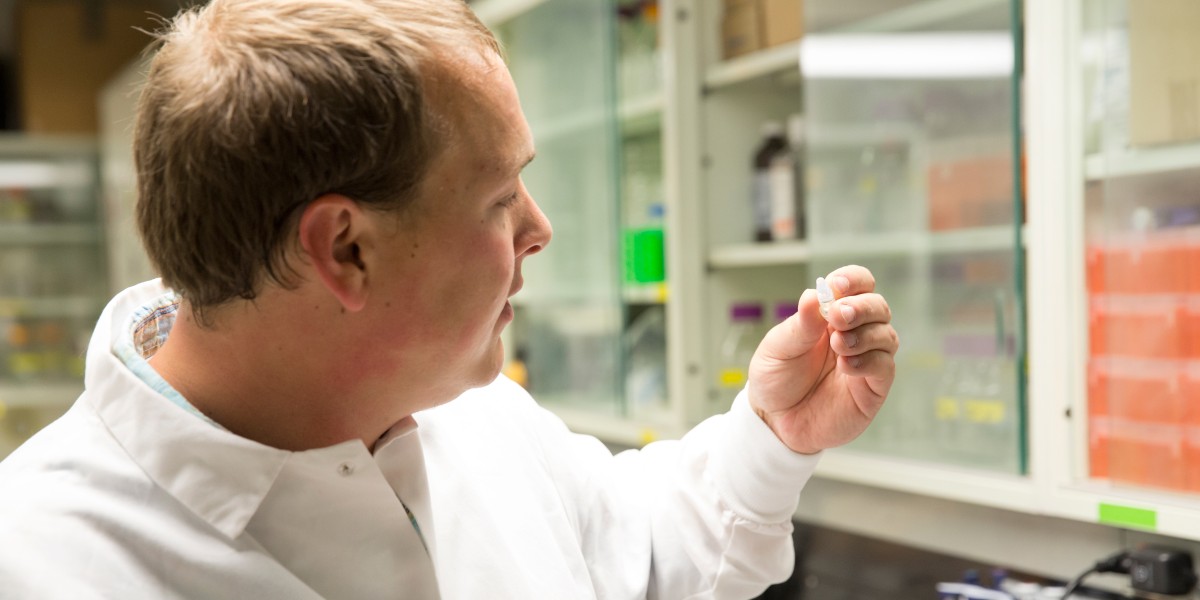

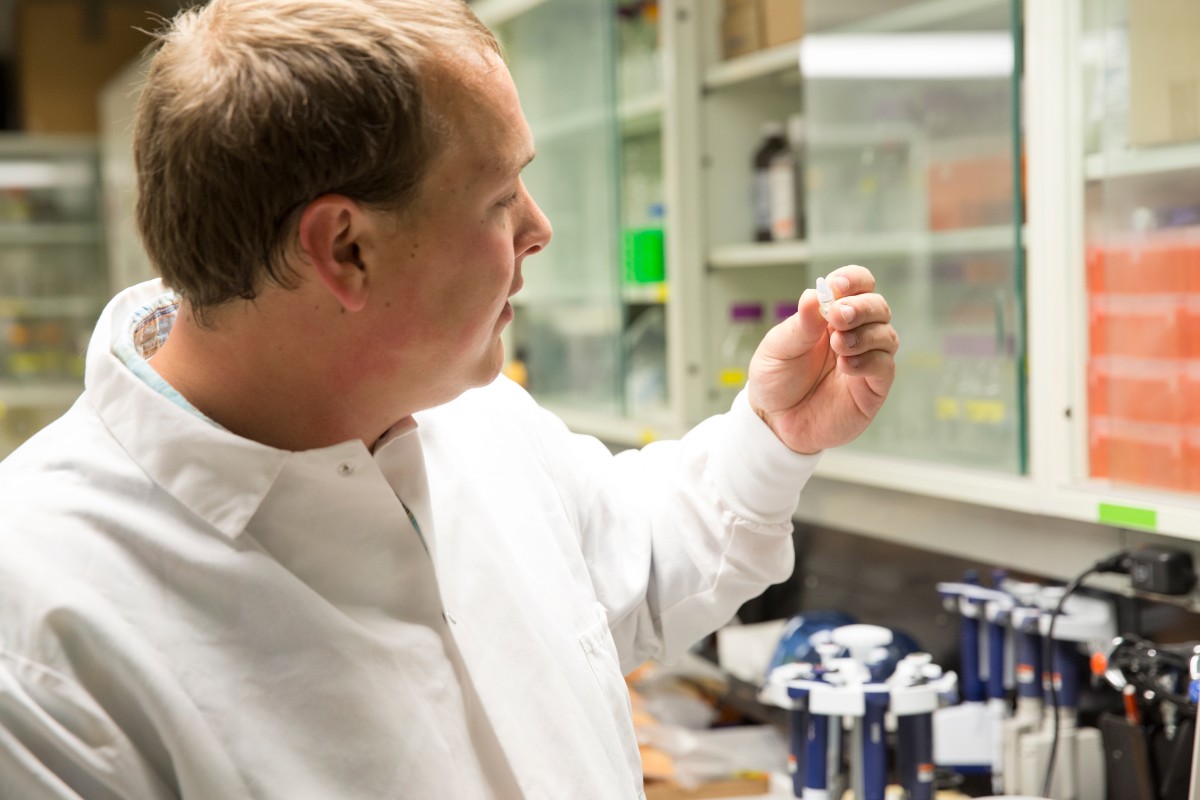

It’s easy to root for Greg Desjarlais, a recent participant in the Research Experience for Undergraduates program offered by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He’s unassuming and easy to talk to. He’s a little self-deprecating and he laughs at your jokes.

Raised in the small farming community of Rio (pronounced RYE-oh) about a 45-minute drive north of Madison, Dejarlais grew up on land he loved, among rural Wisconsin’s cornfields and winding streams. The 33-year-old high school graduate’s résumé includes making engine parts in a factory, managing a convenience store, and working in a warehouse.

But then last year Desjarlais decided he wanted something else – and that to learn more about the landscape he grew up in he needed to make his way instead to libraries, laboratories, and agricultural research stations. Taking a cue from his mother, who went back to school in her 30s, Desjarlais enrolled at Madison Area Technical College (MATC). There he took math and science classes, at first just to catch up but then to get ahead. Meanwhile, he’d woken a dormant interest in genetics and so began to ask around, “Where can I do more of this stuff?”

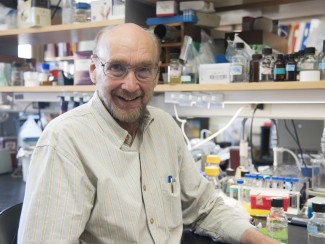

An advisor at MATC pointed him towards the REU program, which provides college students the opportunity to work with an active research program for ten weeks over the summer. GLBRC's Education & Outreach program then connected him with Michael Casler, a professor of agronomy and a research geneticist with the USDA and the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

Though any undergraduate student anywhere can be accepted into the REU program, the program prioritizes applications from students under-represented in the sciences as well as those, like Desjarlais, who did not take a conventional route to their undergraduate education.

With Casler’s permission, Desjarlais started the program early to gain a better understanding of the research. Funded by the GLBRC, Casler seeks to adapt a Southern type of switchgrass, which has a longer growing season than the Midwest’s native variety, to northern climates. Combining fieldwork and lab work, Casler tests the perennial switchgrass for genetic markers that might be the key to life or death after the frost, in order to produce new, highly productive switchgrass varieties.

If successful, the extended growing season of these hardy plants could advance the role of sustainably produced biofuels in our energy system, creating more available biomass for biofuel production without the environmental toll linked to annual bioenergy crops such as corn.

When Desjarlais joined Casler’s team last spring, however, there was only one problem. Due to a mild winter, only about 5% of the plants died off. “As you can imagine, in a place where we're trying to do classical breeding and selection for winter hardiness or cold tolerance,” says Casler, “this is really bad news.”

In stepped Desjarlais. Developing a plan with Casler and others on the team, he mapped out a process to examine all 30,000 switchgrass plants to record the die off, while training other undergraduates to take the samples. Desjarlais also performed DNA extractions and statistical analysis, learning these skills on the fly.

“To a certain degree you learn life skills just working nine to five everyday years on end,” he says.

Casler agrees: “A lot of people who come in, particularly those without a formal agricultural background, require a lot of training to get up to speed and understand what we’re doing. Greg decided he wants to study plant genetics, so he just adapted to it.”

To Desjarlais, the ease with which he adapted comes not just from his work experience, but also from growing up in Rio.

“I love the hustle and bustle of the city, but spending time in any of the research fields just feels like home.”

Starting his sophomore year in the Liberal Arts Transfer Program at MATC this fall, Desjarlais has more goals in mind: applying to the UW–Madison genetics program.

“Following that I could see myself going to grad school either here at or one of the other strong agricultural schools like Iowa, Michigan or Michigan State,” he says.

His preference for now, of course, is to be a Badger.

Meanwhile, Desjarlais has an offer to return to Casler’s lab next summer – or any time he wants. “It's just nice to work with somebody like him who has the motivation and background that allows him to really be good at science,” says Casler. “And he is going to be really good at science. I have no doubt.”