Preface: From minerals to sunlight, the quest to find, harness, and improve energy has helped shape the university's research portfolio

Energy-related research at the University of Wisconsin–Madison evolved over the institution's first 175 years, from departmentally-segregated work focused largely on technological innovation to a more holistic and interdisciplinary approach that bridges technologies, environmental and social impacts, and policy.

Not long after installing the first electric lights on campus, UW–Madison had one of the nation’s top electrical engineering programs, and in the years after the second World War, the university became known for work on nuclear engineering, solar energy, and internal combustion engines.

Coinciding with the energy crisis of the 1970s, there was a new push to think more comprehensively about energy, which spawned the Energy Analysis and Policy program, though the focus remained primarily on supply.

Later, recognition of an impending climate crisis ushered in a new era of cross-disciplinary thinking in the 21st century, with cluster hires that included researchers who together brought engineering, environmental, and policy perspectives as well as the formation of collaborations like Wisconsin Energy Institute and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center.

“We are sitting on a cornucopia of energy excellence,” said Tracey Holloway, a professor of atmospheric sciences and director of the Energy Analysis and Policy program.

While the university has produced thousands of papers and patents that influence policy and undergird technologies, many of those discoveries are often in the weeds.

“It's not like there's some major piece of handheld technology that people can associate with our department here, like an iPhone or something like that,” Wilson said.

Perhaps the biggest single contribution is the alumni, including many serving as leaders of local, state, and national government agencies as well as private industry.

“Our main product is the student,” said Greg Nellis, director of the Solar Energy Lab. “I think that's going to be our continuing legacy.”

UW–Madison: 175 Years of Energy Research

Part 1: Energy Underpinnings

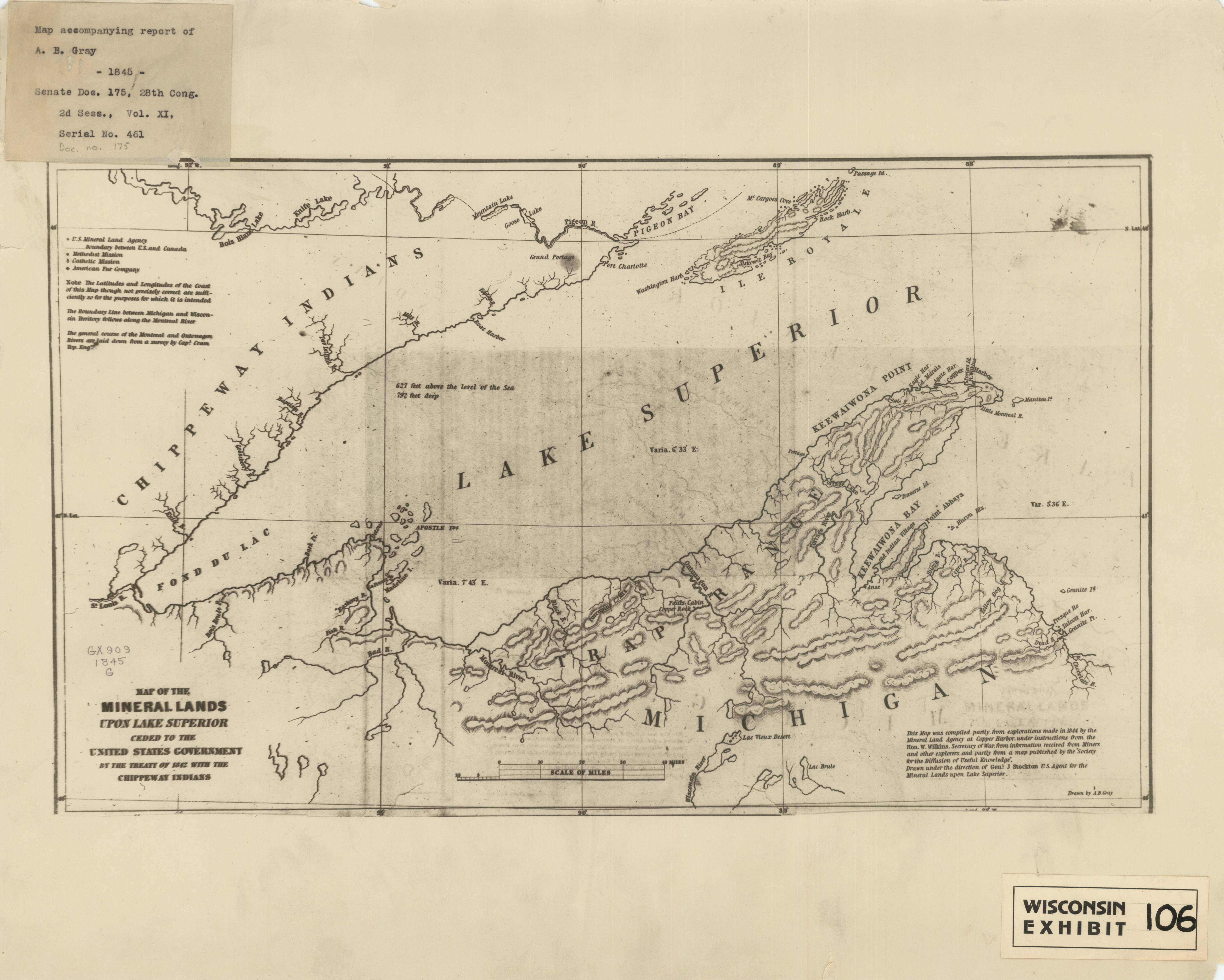

Even in the days before energy was a topic of research interest, the quest to power an industrialized economy guided the university's mission.

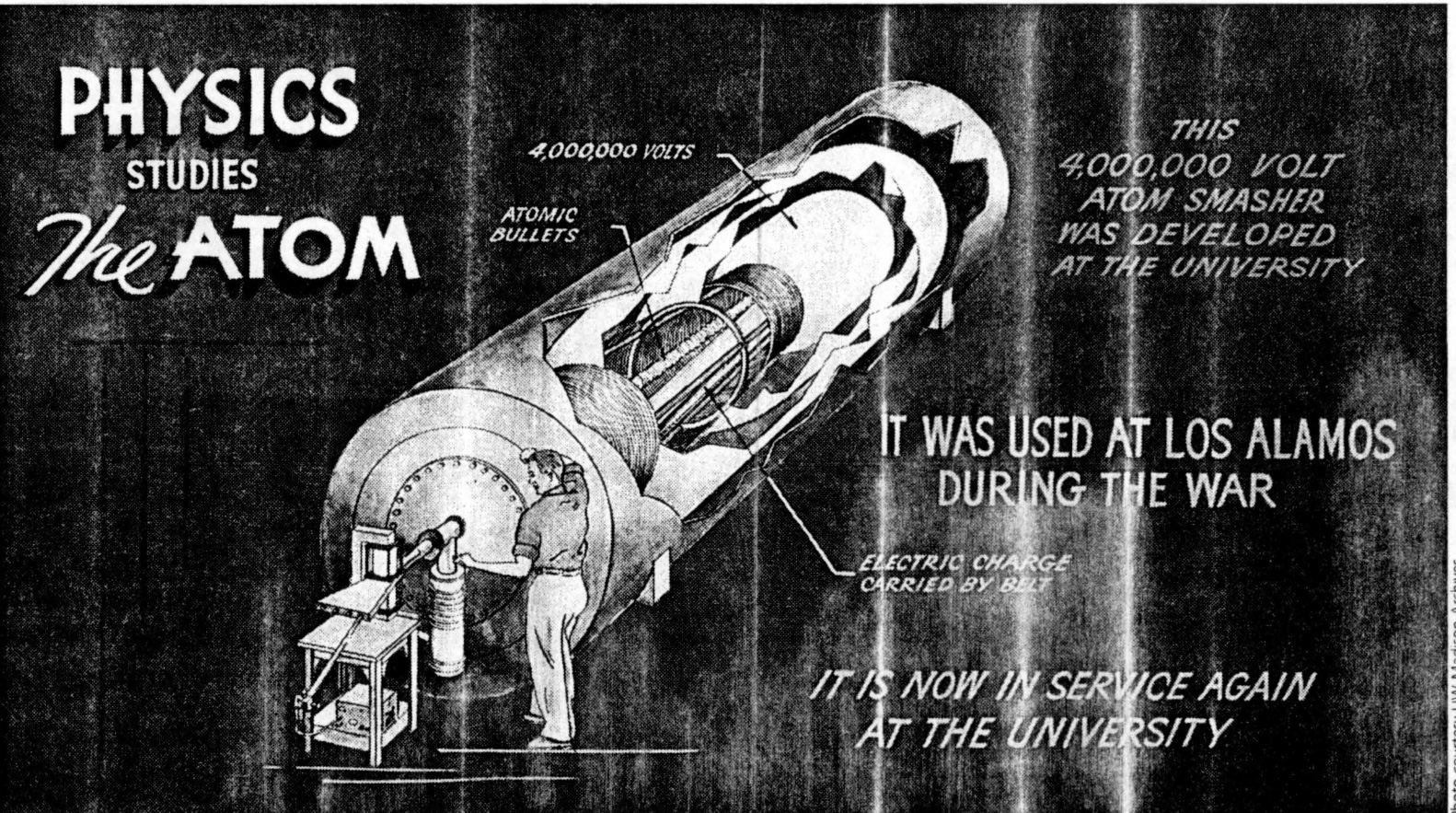

Part 2: The Atomic Age

From the Manhattan Project to fusion energy, UW–Madison scientists have been at the forefront of nuclear science and engineering.

Part 3: Connecting Dots and Breaking Down Silos

Starting in the 1970s, UW–Madison researchers began thinking more holistically about energy and the connections between supply, pollution, and policy.

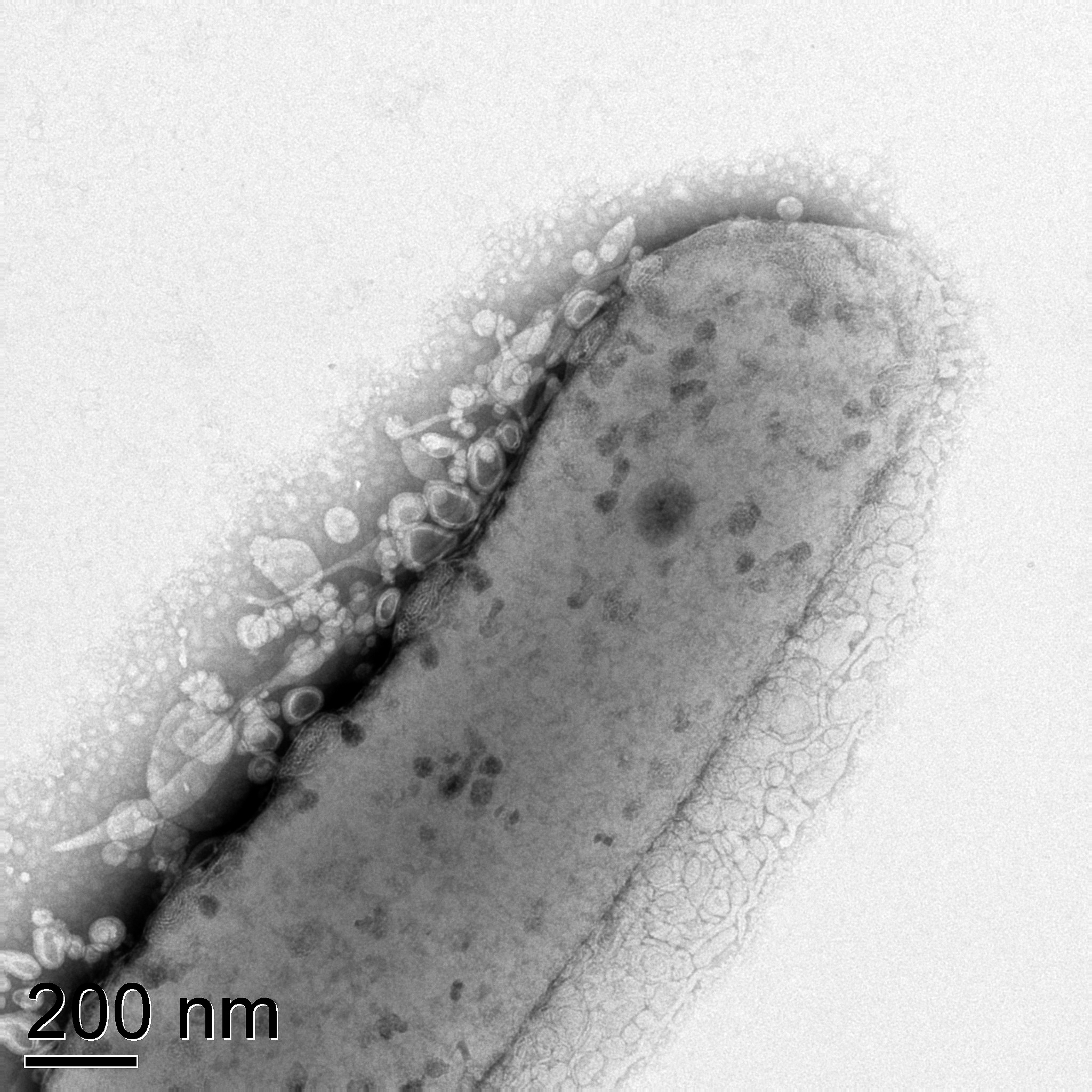

Part 4: Bioenergy

UW–Madison scientists look to the tiniest lifeforms to solve some of the world's largest problems: namely, producing sustainable plant-based alternatives to fossil fuels and petrochemicals.

Part 5: Power to the People

For all the thousands of discoveries and patents UW–Madison has produced, perhaps the biggest contribution to energy research is the graduates who continue to push the field forward.

Timeline

Explore energy milestones over the course of UW–Madison's first 175 years.