On Tuesday, NovoMoto – an innovative start-up co-founded by two University of Wisconsin–Madison graduate students in engineering – won $90,000 in the Clean Energy Trust Challenge, a start-up contest billed as the “largest single-day clean energy pitch competition in the nation.”

Aaron Olson and Mehrdad Arjmand, NovoMoto co-founders, competed against three other student teams and fourteen teams overall to win a chunk of the $1 million in prize money. They will use the funds to bring a reliable source of electricity to the residents of Mboka Paul, a small village in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) located one hour east of the country’s capital Kinshasa. Olson, who was born in the DRC and moved to the United States with his parents at an early age, knows the village of Mboka Paul quite well as his aunt lives there and his family has farmland nearby.

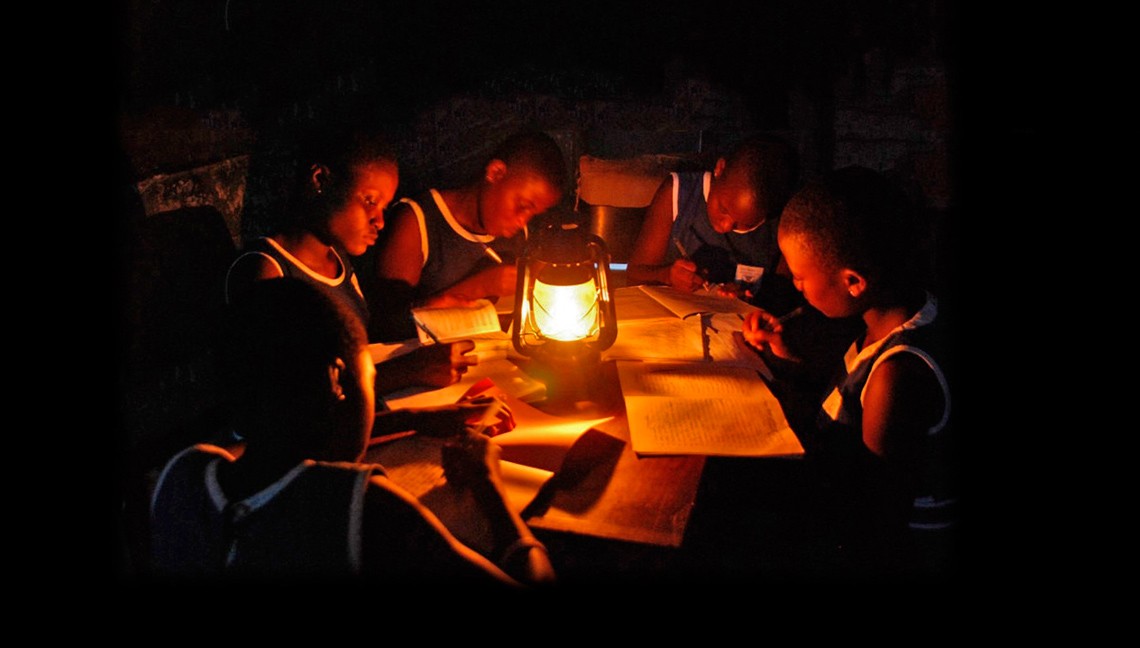

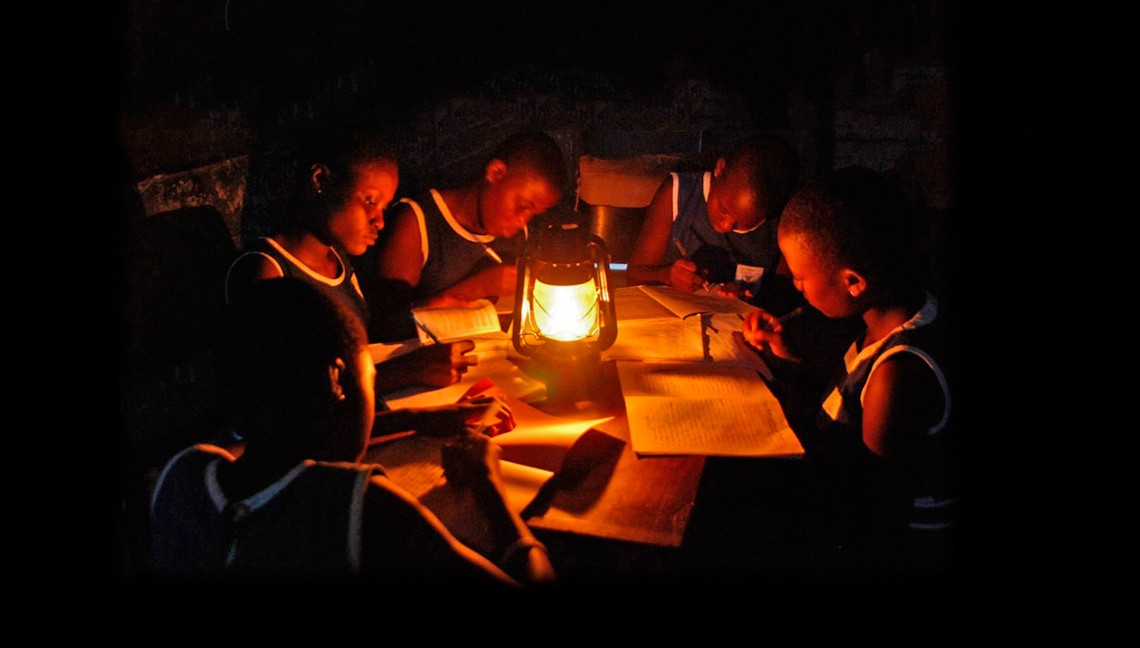

Currently, 68 million DRC citizens (roughly 90% of the country’s population) lack a reliable source of electricity. To power up, they often buy kerosene to burn in lamps for lighting and pay for local diesel generators to charge their phones. Arjmand and Olson say the current energy scenario is not only expensive – some residents spend up to one-third of their income on these services – but also inefficient and poses significant environmental and health risks.

Though a high-voltage power line runs above the village of Mboka Paul, none of the residents have access to the electricity it carries. For a reasonable cost, Olson and Arjmand plan to provide the villagers with rechargeable batteries that can store enough energy to charge a cell phone, power a small TV, radio, or fan, and provide up to six hours of light via three 3-watt LED bulbs. Customers can then bring their depleted batteries to a NovoMoto control station, powered by six 285-watt solar panels, and exchange them for fully charged units.

“What’s useful is that we don’t have to set up a distribution line to deliver energy to customers,” says Olson. “They carry it around with them, come to our location where we have the panels set up with energy storage, then just take that power home home in a portable battery.”

Getting the NovoMoto project off the ground will be simplified by the fact that Olson’s aunt and cousins live in the neighborhood. Having local connections means being able to utilize existing distribution chains, including entrepreneurs who are already selling phone cards, water, medicine and anything else villagers might need.

“Instead of coming in as a foreign entity to sell a service that members of the community aren’t familiar with, we’re recruiting these local business people to join the NovoMoto team,” says Olson.

“Having the funds and guidance to start the pilot phase is critical,” says Arjmand. “Now we’ll be able to interact with customers to offer them what we think is a good solution, and receive feedback to make the product better.”

This summer, with seed money in hand to complete a prototype, Olson and Arjmand will return to Mboka Paul to assemble the first NovoMoto solar power kiosk. Having received video testimonials from villagers about the product’s potential, they’re optimistic.

“The feedback so far is that it’s a no-brainer,” says Olson. “The villagers are basically saying, ‘who wouldn’t want this service?’”

While Olson and Arjmand fully intend to complete their graduate degrees, they are simultaneously committed to – and very excited about – getting NovoMoto off the ground.

“At some point it may be appropriate to step down and let someone else continue the business,” says Olson, “but we’ll make that decision after it’s successful.”