Nuclear energy is having a moment in Wisconsin.

Just a few years ago, the technology seemed to be heading for the exits, at least in the United States. Aging plants across the nation were shutting down, unable to compete with cheaper electricity sources like wind, solar, and gas.

Since the late 1970s, only two new plants had been approved for construction. One was abandoned; the other took 15 years to complete, at a cost of more than twice the original estimate.

But with new data centers threatening to overwhelm the current grid, nuclear power — including traditional fission plants, experimental small reactors, and potentially fusion — could be on the verge of a renaissance.

“I believe there’s a bright future for nuclear,” said Ben Lindley, an assistant professor of nuclear engineering at UW–Madison. “We are going to need additional sources of energy for a host of reasons — including but not limited to energy security.”

Republican state lawmakers have introduced a package of bills aimed at turning Wisconsin into “the ‘Silicon Valley’ for nuclear technology research and development,” according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

One bill would create a state board to “organize, promote, and host a Wisconsin nuclear power summit in the city of Madison to advance nuclear power and fusion energy technology and development and to showcase Wisconsin’s leadership and innovation in the nuclear industry.”

Another would require state utility regulators to conduct a nuclear power siting study and to develop an approval process for small modular reactors, a new technology that has yet to be commercially deployed.

Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, requested $1 million in his next two-year budget proposal for a study on possible sites for new nuclear power plants, suggesting there may be room for rare bipartisan agreement.

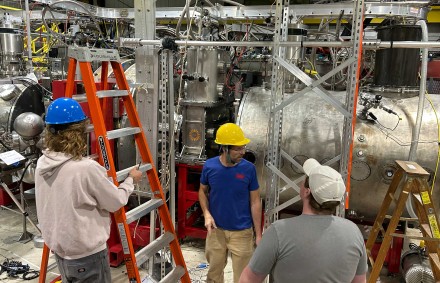

Lawmakers are also seeking to capitalize on the state’s leadership in nuclear fusion, which is the source of the sun’s energy. If scientists can overcome the engineering challenges of containing and controlling fusion reactions on Earth, it would unlock virtually limitless clean power with none of the radioactive waste created by fission reactors.

UW–Madison has one of the nation’s oldest and broadest fusion research programs, and the state is home to three companies working to commercialize fusion energy, including UW–Madison spinoffs Shine Technologies and Realta Fusion, which last summer produced plasma for the first time at the university's Physical Sciences Laboratory in Stoughton.

The push comes amid a boom in data processing centers. These centers, which support artificial intelligence as well as nearly every aspect of modern life, can use more power than an entire city.

Data centers tend to need steady, on-demand power, and many of the tech companies building them have pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions, making nuclear an ideal fit.

Owners of shuttered nuclear plants in Iowa, Michigan, and Pennsylvania have announced interest in resuming generation to serve data centers.

“I think the trend is an ever broader political recognition of the importance of keeping nuclear power plants open,” Paul Wilson, chair of UW–Madison's nuclear engineering department said in an interview last fall.

The U.S. Department of Energy says the nation’s nuclear generation capacity — currently about 100 gigawatts — could triple by 2050, buoyed by data center demand.

The consulting firm Wood Mackenzie predicts something closer to 10% growth in domestic nuclear capacity, though analyst Ed Crooks says artificial intelligence and data center demand could change that outlook.

“If they’re going to be built, we need reliable clean energy to power them,” Wilson said. “It would be a real shame if we had coal and natural gas being built in order to power those things. And so I think nuclear is really one of the best bets.”

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing nuclear power is time: a plant that takes 15 years to build is not much help to a data center in this decade.

But despite the setbacks plaguing recent U.S. projects, Wilson said it shouldn't necessarily take a decade to bring a plant online.

“They've done it in the (United Arab Emirates) in four years. They do it in China in four years," Wilson said. “We know it’s possible. I wouldn’t assume that we can just snap our fingers and do it in four years, but there’s no reason it should take 12.”

Lindley says it will just take one project completed on time and under budget.

“If we manage that, then I think the floodgates will open,” he said. “If someone delivers a successful greenfield plant in the U.S., I think we’ll get many more.”

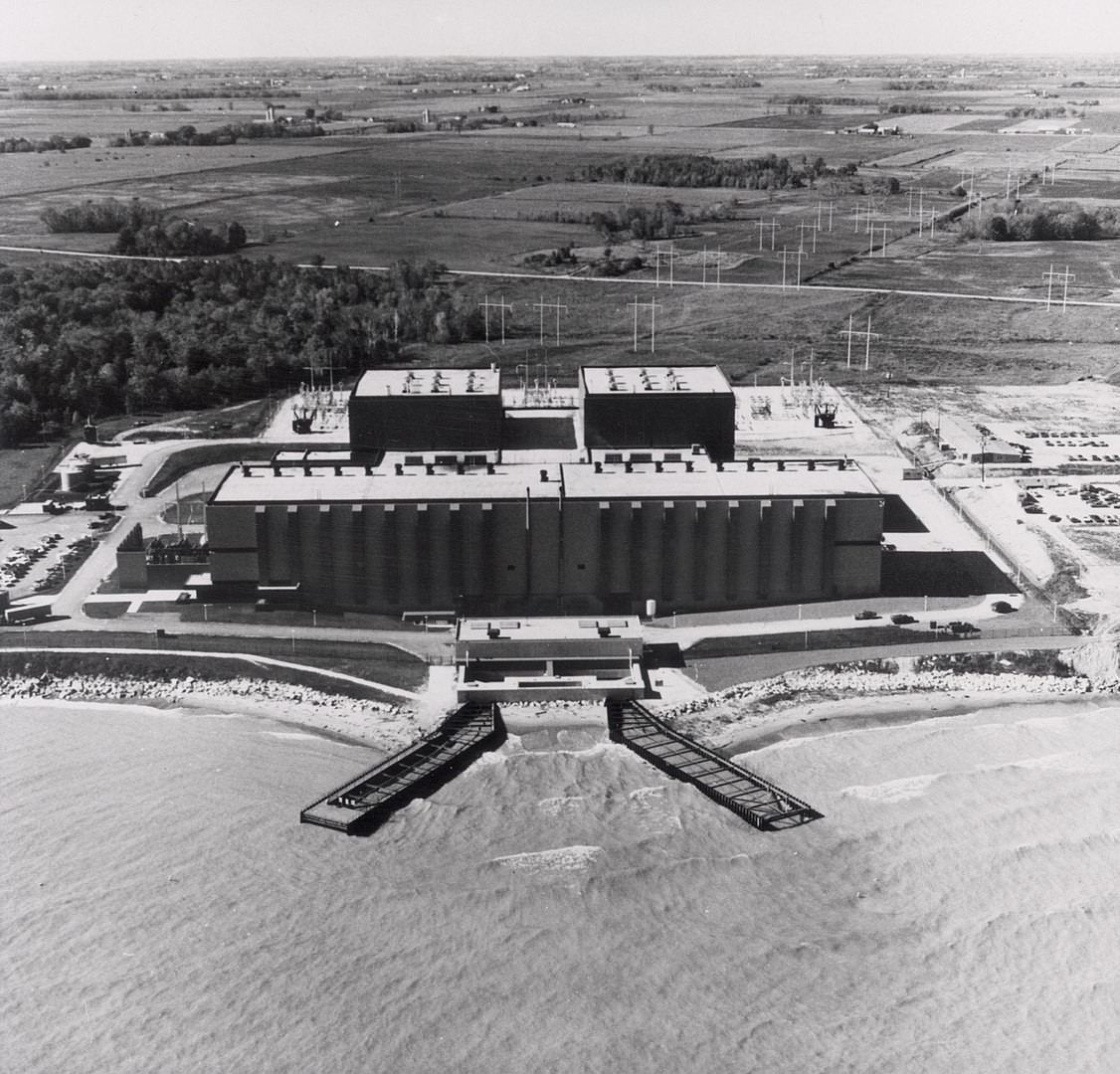

It's been more than half a century since Wisconsin approved construction of a nuclear power plant, and nine years since the Legislature lifted a 33-year ban on new construction.

And there are no active proposals to build a new plant, though La Crosse-based Dairyland Power Cooperative has signed an exploratory agreement with a company seeking to commercialize a small-scale “advanced reactor” design. (Dairyland also operated the state's first nuclear reactor, a small demonstrator plant on the Mississippi River that shut down in 1987.)

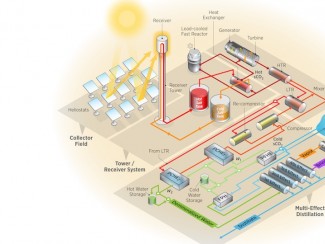

Testifying at an Assembly committee hearing Wednesday, Wilson said the industry is simultaneously moving in several directions — including large plants like those currently in use as well as small and “micro-scale” reactors — that will provide far more flexibility in terms of siting and applications.

Lindley and Wilson recently conducted a study that identified more than 180 U.S. government facilities with power demands that would benefit from small nuclear reactors to increase resilience and lower carbon emissions.

This type of arrangement, where the government serves as a guaranteed consumer for projects built with private funding would help bridge the “valley of death” that lies between invention and economically competitive deployment.

“The prospect of deploying hundreds of microreactors opens the door for learning-by-doing that has benefitted wind and solar as well,” the authors wrote in a Nelson Institute policy brief.

Meanwhile, the owner of the state’s sole operating nuclear power plant, which began operation in the early 1970s, is currently seeking a license extension to run the plant through 2050.

Lindley has seen the pendulum swing both ways in his career.

“I first went into nuclear power in the late 2000s when I finished my undergrad degree and I did my PhD in the early 2010s and that was a time when people were saying, ‘Hey, nuclear is back on the agenda. We're going to build lots of new reactors,’” Lindley said. “Then Fukushima happened, which slowed a lot of things down.”

By the time he joined UW–Madison in 2020, Lindley said he was unsure about advising students to pursue nuclear engineering.

“Now I have no doubt,” he said. “If my own daughter said, you know, I want to be a nuclear engineer, I’d say, great. You’ll have a fantastic career.”