Last week’s commencement ceremony at Camp Randall was not the first time this spring that University of Wisconsin–Madison senior Drew Dillmann had reason to celebrate. Just one month earlier, he and his teammates placed second in the Department of Energy’s third annual Race to Zero Student Design competition, in the “Urban-Single Family Housing” category.

The experience is also playing a key role in Dillmann’s job search. “In my last interview, this was pretty much all I talked about,” he says. “I was fairly certain I wanted to work in the building industry, but this solidified my decision.”

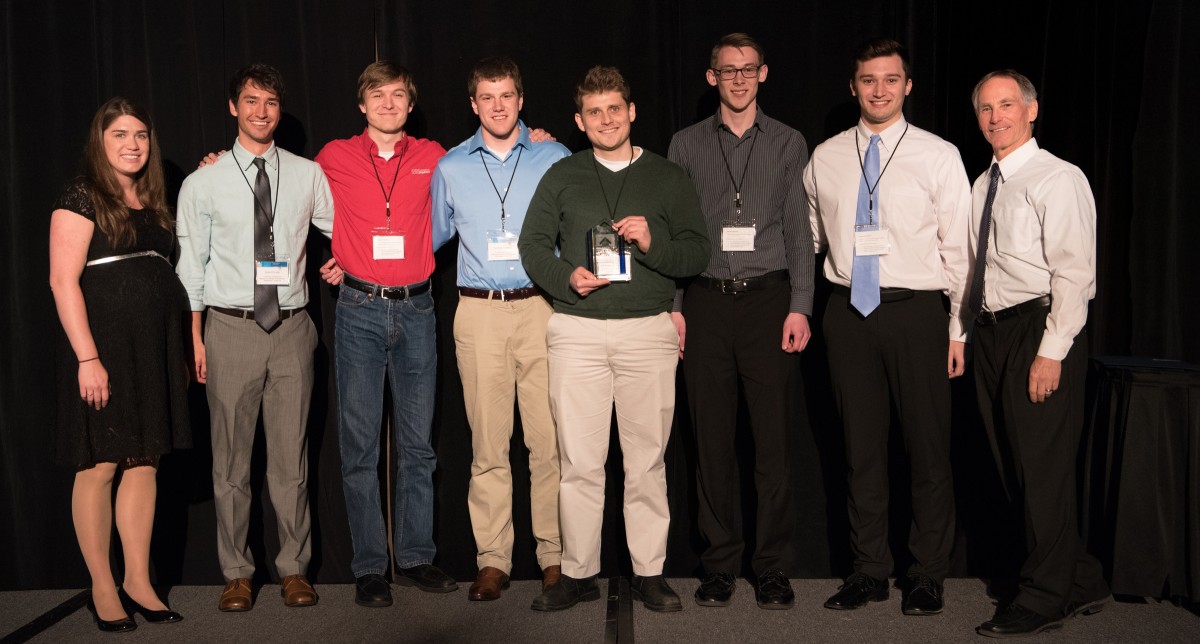

Last fall, Dillmann and fellow mechanical engineers Nicholas Scharping, Daniel Baker and Jacob Moffatt joined Robert Schaffer, interior design student from UW–Madison’s School of Human Ecology, and Laura Valdivia, Nasim Shareghiboroujeni and Jonathon Nelson from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning to form the “Net Zero Wisconsin” team, representing their home state for the first time in the Race to Zero competition.

The team’s main charge was to design a zero energy-ready home—capable of producing as much energy as it consumed with rooftop solar panels—for Milwaukee’s Franklin Heights neighborhood, an area where foreclosures during the Great Recession left behind many vacant lots.

But a second constraint was equally important. “The students had to design a home capable of generating a zero energy balance while also being affordable for someone making Wisconsin’s median income of $51,000,” explains Michael Cheadle, the team’s advisor and a senior design program coordinator in UW–Madison’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. “That’s because the competition’s goal is to have a real impact on net zero housing in the community. A developer could take the students’ plans and actually build the house.”

So what does it take to build a net zero home in Wisconsin? First and foremost, a passive solar design that can heat the house during the winter, but also keep it comfortable on hot summer days. While south-facing windows are ideal for this design, the students had to consider their site’s limitations.

“We selected a lot with an east-west orientation whose south side was blocked off by adjacent houses,” Dillmann says. “Since this was typical for most of the neighborhood, we wanted to develop a design that would address this limitation.”

Their solution was a second-floor dormer that lifts the rooftop solar panels—whether installed at construction time or down the road—high enough to be powered year-round, combined with an open stairwell to extend the area receiving natural light into the first floor.

Insulating against cold Wisconsin winters was another challenge.

Energy conservation is a topic that is here to stay. With so many available jobs in the building industry, this is a great platform for our students to get involved in.

Michael Cheadle

“You basically need to wrap the house in an air and vapor barrier while maintaining the ability to circulate fresh air,” Cheadle says. “That means strategically placing the minimum required number of ducts so that the inside and outside air can be exchanged most efficiently.”

Other notable features of the house—dubbed “Forward Home” after Wisconsin’s state motto—include wheelchair accessibility on the first floor to allow for a family’s “aging in place,” and a Nest thermostat that conserves energy by learning to predict a homeowner’s behavior, such as when she will most likely want a hot shower.

For Dillmann, who fondly remembers the team’s “charrettes”—architect lingo for all-day team meetings dedicated to brainstorming and decision-making— designing “Forward Home” was an opportunity to experience the collaborative nature of net zero home building.

The competition also helped Cheadle realize his long-standing plan of forming an undergraduate student chapter of the American Society of Heating, Refrigeration and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), as well as to begin assembling teams for other student competitions, such as the Solar Decathlon, a technology-based competition requiring more planning and an application for financial support.

“Energy conservation is a topic that is here to stay,” he says. “With so many available jobs in the building industry, this is a great platform for our students to get involved in.”

The Net Zero Wisconsin team drew additional support from Lesley Sager, faculty associate in UW–Madison’s School of Human Ecology, Mark Keane, professor in UW–Milwaukee’s School of Architecture and Urban Planning, and three industry collaborators: Focus on Energy; Gorman USA, a developer that owns many of Franklin Height’s vacant lots; and Unico, a heating and cooling systems manufacturer.