The 15 teachers attending the Energy Institute for Educators this week may have come from different directions, from Salem or Green Bay, Medford or Mosinee, but they’re all heading home to the same challenge: engaging their students in the contemporary science of energy.

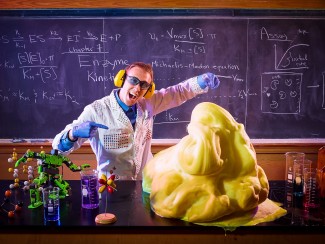

Organized by the Wisconsin Energy Institute at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, this four-day institute invites teachers with students ranging from the sixth grade to college to explore ways of bringing cutting edge energy research into their science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) classrooms.

“Our goal is to help teachers ask questions that are highly relevant to today’s energy needs,” says Leith Nye, education and outreach coordinator at the Wisconsin Energy Institute. “Teachers see firsthand how UW scientists are tackling some of our most pressing energy challenges and then how to bring those real and urgent challenges back to their students.”

This year’s program focuses specifically on merging science and engineering practices to better understand energy, sustainability, and climate change. “Energy is a perfect topic for illustrating the benefit of studying STEM fields from an interdisciplinary perspective,” Nye says.

With workshops on energy and sustainability, solar photovoltaic technology, sustainable bioenergy and biofuels, and microgrids and energy systems, teachers gain an improved understanding of current energy research and sustainability issues and explore education materials related to these topics for use in their classrooms.

Lisa Swaney, a middle school science teacher from Rhinelander, Wis., attended last year’s institute. With a year of teaching new energy activities under her belt, Swaney calls the experience “truly valuable.”

“I came with a colleague who teaches high school,” Swaney says. “At the institute, we worked as a team to write compatible physical science curriculums for middle and high schools in our district. Together, we figured out the ways we could incorporate what we were learning into those curriculums.”

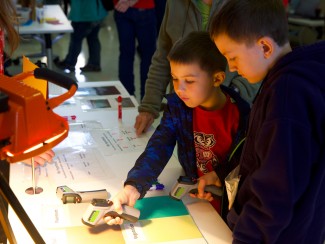

Throughout the educational program, emphasis is placed on an interdisciplinary approach to understanding energy challenges and on fundamental but cross-cutting concepts – i.e., energy flows, cycles, and matter – that are critical to understanding energy systems. Nye says the institute aims to give students the kind of problem-solving skills necessary to navigate a complex world of competing energy sources and systems.

“Knowing how to evaluate the pros and cons of traditional power plants, solar, microgrids, or biofuels from social, economic, and environmental perspectives is a very important skill,” Nye says. “Not only for future scientists and policymakers, but for informed citizens as well. We want the students to know how to ask the right questions and to begin thinking creatively in formulating their own answers.”

According to Swaney, the time spent at last summer’s institute helped improve her curriculum and her teaching.

“I gained a lot of knowledge about energy science that gave me a stronger base from which to teach about alternative energy,” Swaney says. “It definitely gave me a kind of exposure that had been missing.”

For more information on the Energy Institute for Educators, visit the webpage.