Potentially improving the energy storage of everything from portable electronics to electric microgrids, University of Wisconsin–Madison and Brookhaven National Lab researchers have developed a novel X-ray imaging technique to visualize and study the electrochemical reactions in lithium-ion rechargeable batteries containing a new type of material, iron fluoride.

“Iron fluoride has the potential to triple the amount of energy a conventional lithium-ion battery can store,” says Song Jin, a UW–Madison professor of chemistry and Wisconsin Energy Institute affiliate, referring to his team’s recent study published today in the journal Nature Communications. “However, we have yet to tap its true potential.”

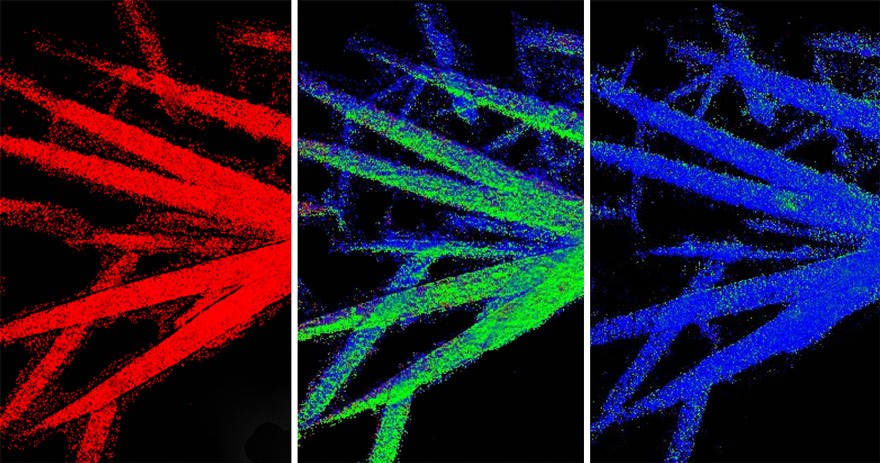

Graduate student Linsen Li worked with Jin and other collaborators to perform experiments with a state-of-the-art transmission X-ray microscope at the National Synchotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Lab. There, they collected chemical maps from actual coin cell batteries filled with iron fluoride during battery cycling to determine how well they perform.

“In the past, we weren’t able to truly understand what is happening to iron fluoride during battery reactions because other battery components were getting in the way of getting a precise image,” says Li.

By accounting for the background signals that would otherwise confuse the image, Li was able to accurately visualize and measure, at the nanoscale, the chemical changes iron fluoride undergoes to store and discharge energy.

Thus far, using iron fluoride in rechargeable lithium ion batteries has presented scientists with two challenges. The first is that it doesn’t recharge very well in its current form.

“This would be like your smart phone only charging half as much the first time, and even less thereafter,” says Li. “Consumers would rather have a battery that charges consistently through hundreds of charges.”

By examining iron fluoride transformation in batteries at the nanoscale, Jin and Li’s new X-ray imaging method pinpoints each individual reaction to understand why capacity decay may be occurring.

“In analyzing the X-ray data on this level, we were able to track the electrochemical reactions with far more accuracy than previous methods, and determined that iron fluoride performs better when it has a porous microstructure,” says Li.

The second challenge is that iron fluoride battery materials don’t discharge as much energy as they take in, reducing energy efficiency. While the current study sheds some preliminary insights into this problem, Jin and Li plan to tackle this challenge in future experiments.

Some implications of this imaging analysis technique are obvious — we’d all like to be able to use our portable electronic devices for longer before charging — but Jin also foresees a bigger and broader range of applications.

“If we can maximize the cycling performance and efficiency of these low cost and abundant iron fluoride lithium ion battery materials, we could advance large-scale renewable energy storage technologies for electric cars and microgrids,” he says.

Jin also believes that the novel X-ray imaging technique will facilitate the studies of other technologically important solid-state transformations and help to improve processes such as preparation of inorganic ceramics and thin-film solar cells.

The X-ray imaging experiments were performed with the help of Dr. Y.-C. Karen Chen-Wiegart, Dr. Feng Wang, Dr. Jun Wang and their co-workers at the X8C beamline, National Synchrotron National Source, Brookhaven National Laboratory and supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy, and supported by a seed grant from the Wisconsin Energy Institute. The synthesis of the battery materials in Jin’s lab was supported by National Science Foundation Division of Materials Research.