Researchers at UW-Madison have helped develop a new system that could make it easier to capture clean energy from the sun and deliver electricity in remote areas.

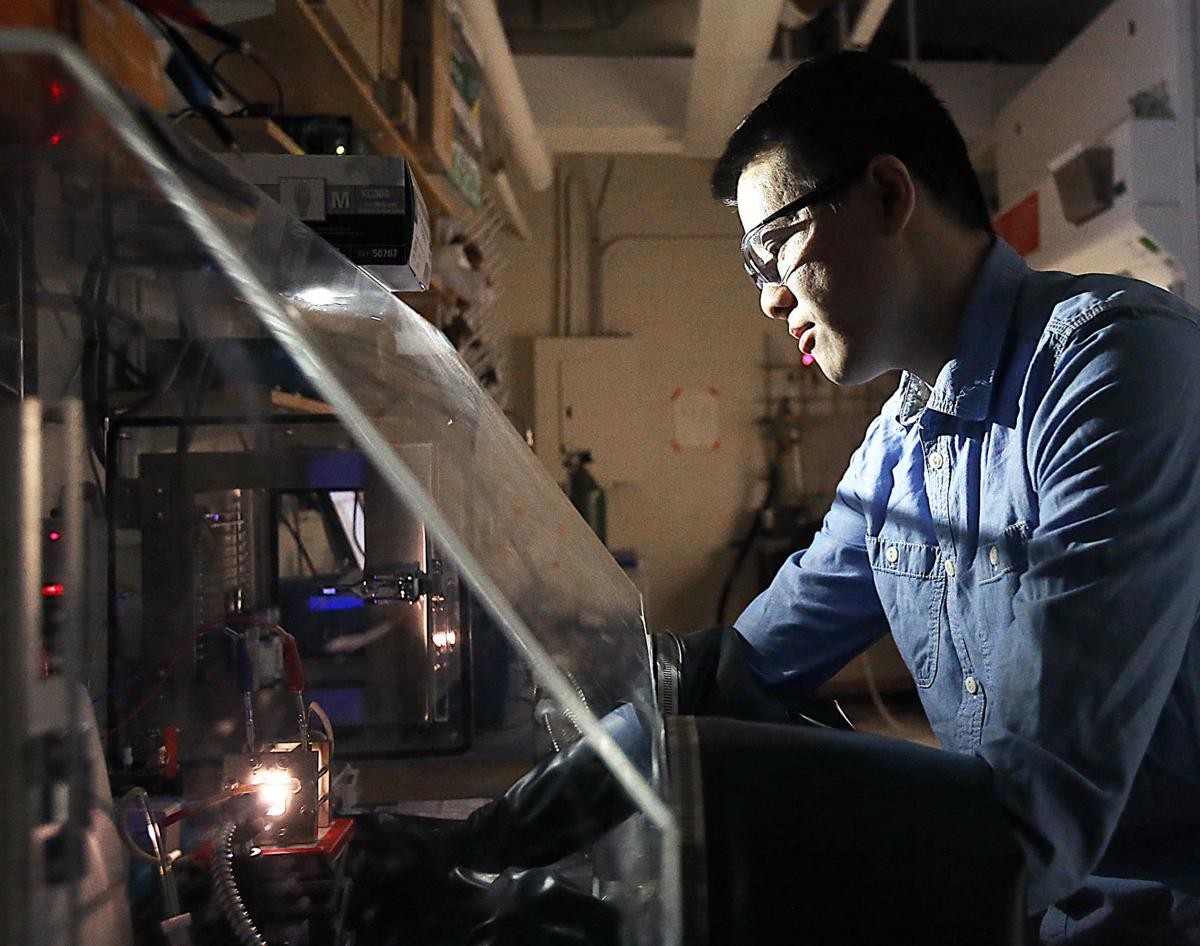

Integrating pieces of existing technology, chemistry Professor Song Jin and research assistant Wenjie Li built a “solar flow battery” that can both generate and store electricity.

Jin and Li, who teamed up with a professor of electrical engineering in Saudi Arabia, detailed the findings of their research in a paper published last week in the journal Chem.

The record-setting 14.1 percent round-trip efficiency rate demonstrated in Jin’s lab on the UW campus is eight times better than the team’s previous efforts and on par with the efficiency of solar cells on the market now, with the benefit of being able to use the electricity any time.

Jin, 43, developed an interest in solar energy about 10 years ago.

Developing reliable renewable energy is one of the most important problems we face, Jin said, and the sun is the most abundant source of energy. Even fossil fuels, he notes, are solar energy captured over billions of years.

But while the sun’s rays are an abundant and clean source of free energy, solar electricity has been limited by a fundamental problem: The sun goes down at night and doesn’t shine as bright on cloudy days, yet people still expect their lights, televisions and computers to work on demand.

“You can’t say I want it now,” Jin said. “We don’t have a billion years to wait.”

Companies like Tesla have sunk billions of dollars into developing storage, but lithium-ion batteries have limitations. Flow batteries, which store energy in liquid rather than metal, offer promising potential for bigger applications.

While not yet widely deployed, flow batteries will likely be the dominant large-scale energy storage technology of the future, said Matthew W. Mench, head of mechanical, aerospace and biomedical engineering at the University of Tennessee.

“The main advantage for lithium-ion is high energy density. That’s why it’s great for cell phones and great for cars,” Mench said. “Once you get to large-scale energy storage you’re already out in a field and the space doesn’t matter … what can matter more is the safety.”

Li, a 26-year-old graduate student from Shanghai, suggested building a flow battery into a solar cell, which would make a more compact system and avoid some of the inherent inefficiency of transferring energy to a separate battery.

“What we did is basically said, hey, we can make an integrated device where we can not only harvest the sunlight but store that in chemical energy,” Jin said. “We bypass the step of moving electricity to storage.”

Their device functions three ways: as a solar panel, delivering power directly as it’s produced; it can store it for later use; and it can be charged by external sources like any other battery.

While the design is not likely to change the current electric grid, Jin sees potential for a stand-alone device to deliver reliable power in remote spots, even within the United States.

“Instead of building 100 miles of power line … you could use one of those and you’re all set,” he said.

Small enough to fit in his hand, Li’s test device produces just 6 milliwatts of electricity, so it would take more than 6,000 of them to power a 40-watt light bulb. But Jin thinks the design could easily be scaled up to the size of solar panels now on the market.

Still, he cautions there’s more research to do. He thinks he might eventually be able to reach 25 percent efficiency, but he also wants to find a way to get similar results with lower-cost materials.

While he’s gotten some attention from the solar power industry, Jin cautions there’s a lot of work left before his research is ready for production. After all, he said, the first paper on flow batteries was published in 1985.

“People are asking me, ‘are you going to start a company?’ I might,” Jin said. “There’s a long way from research to development.”