The history of energy-related research at UW–Madison, part 3

An expert on nuclear power plant safety, Wes Foell was appointed to the University of Wisconsin–Madison faculty in 1967, when proponents believed the technology would make electricity “too cheap to meter.”

In 1970, Foell attended the inaugural Earth Day celebration on campus, describing the week-long series of teach-ins as a “catalytic event” that started him thinking about bigger ecological problems. He joined the Sierra Club, which sent him to a Ford Foundation workshop on growth.

“I was a fish out of water,” Foell said. “I was a nuclear engineering professional. I didn't know anything about those things.”

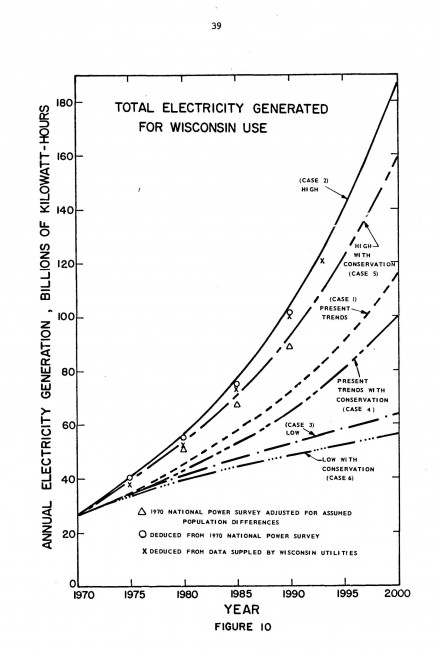

Foell then began collaborating with faculty from other disciplines, including economics, business, and law, on a study of resources, which led him to examine Wisconsin’s energy supply and apply more sophisticated modeling than what the state’s utility regulators had been doing, which assumed historic post-war growth would continue indefinitely.

“They were forecasting with just a ruler on a semilog paper what the future would be,” Foell said.

Foell began collaborating with colleagues from other engineering departments, environmental studies, geology, economics, business to develop an energy seminar, which became known as the Energy Systems and Policy Research Program and led to the development of a Wisconsin Energy Statistics report (which today is issued by the state government), and used computers to model energy demand decades into the future.

In the late 1970s, George Bunn, a professor of law and environmental studies, assembled an interdisciplinary faculty committee to develop a curriculum for a graduate degree in energy studies, which in 1980 was established as the Energy Analysis and Policy program, a 40-credit certificate that could be earned concurrently with a masters degree in land resources, urban planning, or public policy.

Amid flagging enrollment, EAP was modified in 1999 to an 18-credit certificate that can be earned concurrently with any graduate degree and engages students with technical, economic, political, and social factors that shape energy policy formulation and decision-making.

Today more than 300 EAP alumni work for energy producers, environmental organizations, consulting companies, universities, research labs, and state public service commissions.

In 2001, as part of a new “cluster” hiring initiative to foster collaboration across disciplines, the university brought on four energy-focused researchers with backgrounds in nuclear engineering, power systems, air quality, and public policy.

Tracey Holloway, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences, said she was attracted to the relatively novel concept of a position that combined science and policy.

Yet she didn’t think of herself as an energy expert before she applied for the job.

“Many of the people within (the) discipline don't consider themselves an energy person,” Holloway said. “I realized, I study air pollution, and energy is the largest source of many pollutants in the air.”

Paul Wilson, another energy cluster hire who now chairs the nuclear engineering department, said he saw a shift towards more public policy engagement since he was a graduate student in the 1990s.

“Before me, you know, faculty in nuclear engineering had a very technical focus when they were hired,” Wilson said. “I think that there has been a general growth and awareness that technologists need to have a deeper appreciation of the societal framework that they fit into.”

While individual departments and labs represent “a cornucopia of energy excellence,” Holloway, now chair of EAP, said the program has served as “the glue” holding members of her cohort together and has helped leverage those areas of expertise.

“In terms of the bang for the buck, we are doing a tremendous amount on basically a shoestring of a budget,” she said. “We are leveraging the huge investments that are being made on campus – of time, of money, of energy – so that they don't stay locked away in their own departments.”

WEI: breaking down silos

Michael Corradini, a mechanical and nuclear engineer who specialized in reactor safety, joined the College of Engineering in 1981, at a time when research “was very much discipline based.”

In 2005, Corradini emailed then chancellor John Wiley with a pitch to create a cross-campus group to expand the university’s clean energy research and education efforts, which he said was a bid to stay ahead of the competition.

“Everybody thought energy was going to be a booming field of research,” he said. “I thought it'd be silly if we didn't also try to gather things together and form a group.”

Wiley gave the OK, along with a little bit of funding, and the following year the Wisconsin Energy Institute launched as little more than an email list connecting researchers across departments.

Around the same time, the U.S. Department of Energy established the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, an interdisciplinary biofuels research hub based at UW–Madison in partnership with Michigan State University.

To fulfill the state’s obligations under the grant, the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences launched the Wisconsin Bioenergy Initiative with funding from the legislature to create, evaluate, commercialize, and promote bioenergy solutions.

The bioenergy initiative and the energy institute united in 2012 under the WEI banner, and in 2013 WEI and GLBRC moved into a new $57 million building situated strategically between the agricultural and engineering colleges. It was the first physical presence for a university that had more than 90 faculty members scattered across campus working on clean energy.

Current director Tim Donohue said WEI put the university on the map and serves as the campus gateway for energy research.

“We are a front door,” Donohue said.